McLaren Assistance Dilemma And Discovery Learning

How Much Assistance is Needed for Discovery Learning?

Bruce M. McLaren

Overview

PIs: Richard Mayer, University of California, Santa Barbara, Bruce M. McLaren, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh

Others who have contributed 160 hours or more:

- John laPlante, Carnegie Mellon University, programming and website design and deployment

- Krista DeLeeuw, University of California, Santa Barbara, statistical analysis

- Brett Leber, Carnegie Mellon University, programming and website design

- Shawn Snyder, Carnegie Mellon University, programming

- Seiji Isotani, Carnegie Mellon University, research and programming

We have revised the lessons and tests of McLaren et al's stoichiometry tutor for the purpose of this new study. We have also created “voice” versions of each lesson in which the tutor speaks using a friendly human voice, providing the student with hints and error feedback.

In early 2009, we ran both a lab study at the University of California, with over 100 subjects, and a classroom study in 4 high schools in the eastern United States, also with over 100 subjects. We are currently analyzing the results -- preliminary results are discussed below in the "Findings" section -- and we will write a paper based on the studies for submittal to the Journal of Educational Psychology in the summer of 2009.

Abstract

The goal of this project is to examine how student learning is affected by social cues in computer-based learning environments, such as the conversational style of online cognitive tutors. In particular, students will learn how to solve stoichiometry problems in the Chemistry LearnLab, using a cognitive tutor that provides hints and feedback in direct style or in polite style (McLaren, Lim, Yaron, & Koedinger, 2007). The stoichiometry tutor has been used for other PSLC studies, in particular those by McLaren et al that have investigated personalization, politeness, and worked examples.

Our study is based on Brown and Levinson’s (1987) theory of politeness, which specifies how people create polite requests; Reeves and Nass’ (1996, 2005) media equation theory, which specifies the conditions under which people accept computers as conversational partners; and Mayer’s (2005) personalization principle in which people work harder to learn when they feel they are in a conversation with a tutor. Our working hypothesis is that learners work harder to make sense of lessons when they work with polite rather than direct tutors, because learners are more likely to accept polite tutors as conversational partners (Mayer, 2005; Wang, Johnson, Mayer, Rizzo, Shaw, & Collins, 2008).

Glossary

Research Questions

Do polite feedback and hints within a computer tutor lead to more robust learning than direct feedback and hints?

Does polite, audio feedback and hints within a computer tutor lead to more robust learning than text feedback and hints (whether polite or direct)?

Hypothesis

We have two hypotheses, based on these research questions, with the second built on the first:

- H1

- Students will experience more robust learning when they work with polite rather than direct tutors, because learners are more likely to accept polite tutors as conversational partners

- H2

- Students will experience more robust learning when they work with polite tutors that provide audio feedback and hints rather than polite or direct tutors that provide no audio feedback, because learners are more likely to accept audio polite tutors as conversational partners

Background and Significance

The polite tutor uses politeness strategies developed by Brown and Levinson (1978) in which the goal is to save positive face--allowing the learner to feel appreciated and respected by the conversational partner--and to save negative face--allowing the learner to feel that his or her freedom of action is unimpeded by the other party in the conversation. After interacting with the stoichiometry tutor on solving a series of problems for several hours, learners will be given a transfer test based on the underlying principles--including an immediate test and a delayed test. We expect learners who had the polite tutor to perform substantially better on the transfer test than learners who had the direct tutor.

We will also experiment with Clark & Mayer's Modality Principle, in which audio narration replaces onscreen text.

Independent Variables

The independent variables we will experiment with in our studies are politeness (either direct or polite) and audio (hints & feedback in audio or text).

These variables will be crossed, leading to a 2x2 factorial design with the following conditions.

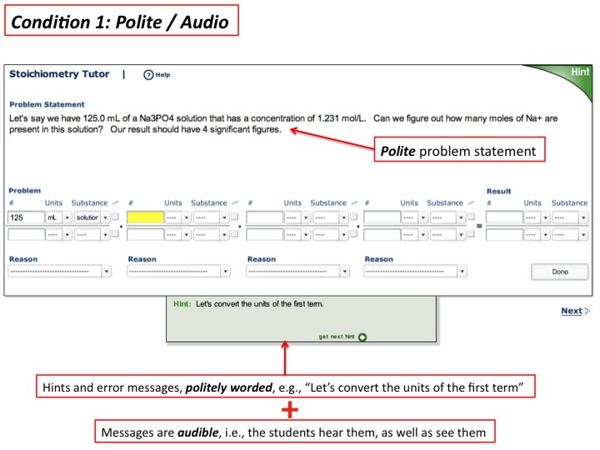

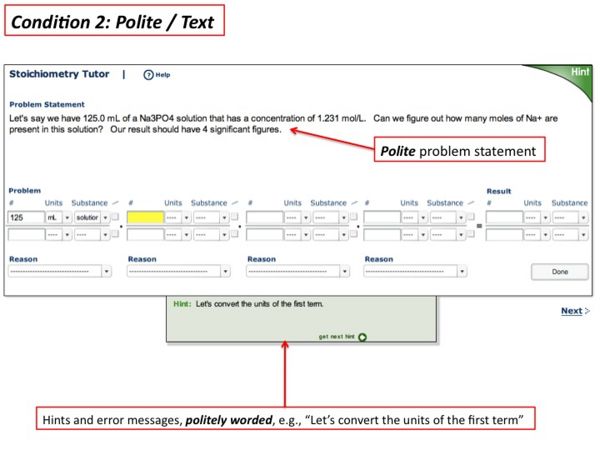

- Condition 1: Polite-Audio: Students work with the stoichiometry tutor that provides polite statements that are spoken

- Condition 2: Polite-Text: Students work with the stoichiometry tutor that provides polite statements that are in text only

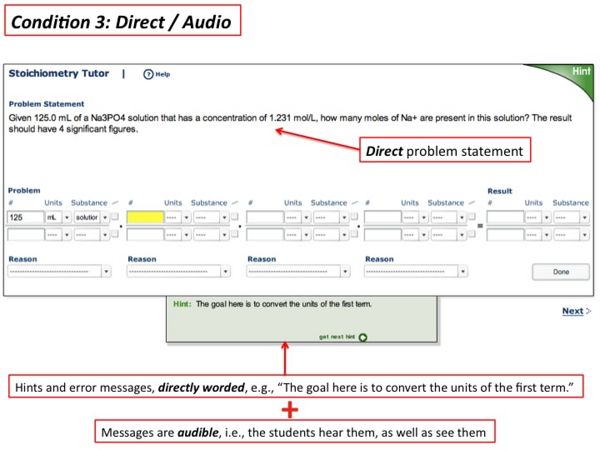

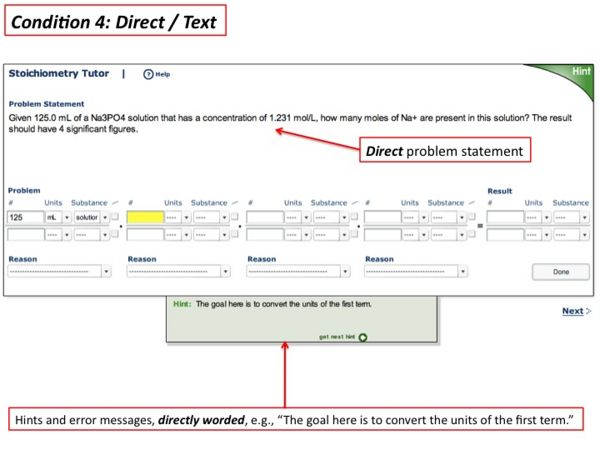

- Condition 3: Direct-Audio: Students work with the stoichiometry tutor that provides direct statements that are spoken

- Condition 4: Direct-Text: Students work with the stoichiometry tutor that provides direct statements that are in text only

Dependent Variables

Our plan is to include the following robust learning dependent variables in our studies.

- Normal post-test: Students will take an immediate post-test, right after completing work with the stoichiometry tutor

- Transfer: Conceptual, transfer questions will be included in the post-tests

- Long-term retention: Students will take a second post-test, including conceptual, transfer questions, 7 days after the initial post-test

Findings

As mentioned above, a lab study with over 100 subjects was run in early 2009 at the University of California with the above conditions. College students learned to solve chemistry stoichiometry problems with the stoichiometry tutor through hints and feedback, either polite or direct, as described above. There was a pattern in which students with low prior knowledge of chemistry performed better on subsequent problem-solving tests if they learned from the polite tutor rather than the direct tutor (d = .73 on an immediate test, d = .46 on a delayed test), whereas students with high prior knowledge showed the reverse trend (d = -.49 for an immediate test; d = -.13 for a delayed test). On the other hand, the high school study, also run in early 2009 with over 100 subjects, produced different results. In particular, the high school students did not show a pattern in which students with low prior knowledge of chemistry performed better on subsequent tests. We are still analyzing the audio feature of the study, i.e., the comparison of audio to text hints and messages, but preliminary results indicate that adding audio hurt the performance of high knowledge learners and helped low knowledge learners on the delayed test.

Explanation

This study is part of the Computational Modeling and Data Mining thrust.

Our explanation for the specific findings from our experiment are soon forthcoming. We are currently preparing a paper for the journal of educational psychology that will provide such an explanation.

Connections to Other PSLC Studies

- This study has a clear connection to the McLaren et al study , in that both studies explore the effect of personalized, polite hints and feedback. In fact, it was through McLaren's original studies, built on earlier work on e-Learning principles by Mayer, that Mayer and McLaren decided to join forces.

Annotated Bibliography

- McLaren, B.M., DeLeeuw, K.E., & Mayer, R.E. (submitted). A Politeness Effect in Learning with Web-Based Intelligent Tutors. Submitted to the Journal of Human Computer Studies.

References

- Brown, P., & Levinson, S. C. (1987). Politeness: Some universals in language usage. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Mayer, R. E. (2005). Principles of multimedia learning based on social cues: Personalization, voice, and image principles. In R. E. Mayer (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning (pp. 201-212). New York: Cambridge University Press.

- McLaren, B. M., Lim, S., Yaron, D., and Koedinger, K. R. (2007). Can a Polite Intelligent Tutoring System Lead to Improved Learning Outside of the Lab? In the Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education (AIED-07), pp 331-338. [pdf file]

- Nass, C., & Brave, S. (2005). Wired for speech: How voice activates and advances the human-computer relationship. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Reeves, B., and Nass, C. (1996). The media equation. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Wang, N., Johnson, W. L., Mayer, R. E., Rizzo, P., Shaw, E., & Collins, H. (2008). The politeness effect: Pedagogical agents and learning outcomes. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 66, 98-112.