Davy & MacWhinney - Spanish Sentence Production

Developing Speaking Skills in a Second Language

| Project Title | The Development of Speaking Fluency Through an Oral Repetition Task | |

|---|---|---|

| Principle Investigator | Colleen Davy (Carnegie Mellon University) | |

| Co-Principle Investigator | Brian MacWhinney (Carnegie Mellon University) | |

| Study Start and End Dates | Study 1: Spring 2009 | |

| Study 2: Spring 2010 | ||

| Study 3: Fall 2010 | ||

| Study 4: Summer 2011 | ||

| LearnLab | N/A | |

| Number of Participants | ~80 | |

| Participant Hours | ~200 | |

| DataShop | Transcriptions of Studies 1, 2, and 3 available upon request | |

| Current Status | Studies 1-2 complete; Study 3 currently being analyzed; Study 4-5 being transcribed/coded |

Contents

[hide]Abstract

This study investigates the use of an oral repetition (listen-and-repeat) task on improving second language speaking skills. Studies 1, 2, and 3 looks at how this task improves speaking skills in proficient learners of Spanish; Studies 4 and 5 look at using this task in beginning learners, to see whether novice language learners can benefit from repeated speaking practice.

Study 1 was a pilot study looking at whether repeated practice leads to improvements in terms of fluency and accuracy. Participants listened to a sentence and repeated it back four times in a row. We found that participants improved both in their ability to correctly and completely repeat the sentence back and the amount of time they needed to repeat the sentence. Study 2 included a post-test where participants produced sentences similar to the ones on which they were trained, and also looked at the difference between training in phrases versus longer sentences. We found a tradeoff between fluency and accuracy, with the phrase condition generally leading to more accurate but less fluent production than the sentence condition, and an opposite pattern with the sentence condition. However, we found that training on very long sentences for part of the training led to increase in fluency, on top of the increase in accuracy from training in phrases. This suggests that both types of practice are necessary for improving speech production. Study 3 used a number of different test tasks at both pre- and post-test, to see what language skills are enhanced through the practice. We have found that oral repetition practice increases accuracy between pre- and post-test on all three tasks we provided. Furthermore, comparing performance on sentences containing verbs that had been trained to those that had only been seen during the pre-test, we saw that trained verbs were produced with significantly more accuracy than those that had not been trained. However, we did see improvements on both trained and untrained items, suggesting that there is some general benefit to the practice.

Study 4 investigates using the oral repetition task with novice learners. In Study 4 we compare using the oral repetition task with a condition that listens to another speaker complete the task. Participants receive instruction on German grammatical gender and how to conjugate verbs in the present tense, then received practice producing sentences using the oral repetition task. In addition to comparing listen-and-repeat to merely listening as a method of receiving exposure to the language, one condition initially received practice on individual vocabulary items before practicing full sentences; the other condition immediately started producing sentences. We are currently completing this study and hope to have results available by the end of Summer 2012.

Background and Significance

It has long been accepted that repeated practice is necessary for the improvement of any new skill, from motor skills to playing a musical instrument to complex math equations. Traditionally language classrooms consisted solely of repeated practice, either through the audiolingual method of listening and repeating to the grammar-translation method of repeatedly conjugating verbs and translating sentences. However, the introduction of the communicative language teaching framework has led to a deemphasis on repeated practice, and even an eschewing of this type of activity as non-realistic and pointless. Recent studies have shown, though, that repeated speaking practice leads to improvements in fluency (de Jong and Perfetti, 2011), complexity (Bygate, 2001) and sometimes even accuracy (Yoshimura and MacWhinney, 2007). SLA researchers and second language educators are beginning to see the benefit of repeated practice on open-ended speaking tasks and are beginning to develop activities that can provide repeated rehearsal, but are still greatly emphasizing the need for realistic contexts. The tradeoff, however, is that this type of practice has less control over the vocabulary items and grammatical structures that can be rehearsed, as students in these contexts will often use more familiar structures to compensate for the need for greater fluency or accuracy during these tasks. Furthermore, the emphasis on speaking skills often does not occur until the learners have achieved a certain level of proficiency in the language, meaning that beginning learners often do not receive focused speaking practice. We suggest that sacrificing context in the name of providing repeated speaking practice on specific grammatical items and vocabulary will not completely negate the effectiveness of the practice, and that repeated practice opportunities can lead to gains in speaking performance in both accuracy and fluency

Yoshimura and MacWhinney (2007) implemented an oral repetition task to improve speaking in Japanese learners, having them practice reading aloud Japanese sentences containing between 0 and 3 novel words. They found that reading aloud improved fluent speech in terms of the length of utterance (how long it took them to read the sentence from start to finish) and the number of errors. A pilot study for the current line of research showed that the same pattern of results occurred when students of Spanish instead repeated sentences they heard. In this study, students heard a sentence, repeated it back, then were asked to a) translate the sentence into English and b) rate their speech in terms of fluency. They repeated this four times for each sentence. They showed that tasks like this, which allow repeated practice in the short term on highly constrained sentences containing target vocabulary, can lead to increases in fluency and accuracy. Furthermore, the lower task demands (read aloud or say from memory) allows for focus on more challenging vocabulary and grammatical structures.

We suggest, then, that using repeated tasks like the one used in this line of research, can lead to the improvement of speaking skills and the acquisition of second language vocabulary and morphosyntax, even in beginning learners.

Glossary

Research Questions

1. During an oral repetition task, do students increase fluency in terms of the time it takes them to repeat back the sentence?

2. Does this task help students increase fluency in terms of the amount of errors they make?

3. Are students aware of their own speech, to the extent that they can accurately rate their own performance?

4. Will students be able to transfer their increased fluency to novel sentences?

Study One

Study one tested whether or not a repetition task could increase fluent production of the sentences.

9 third and fourth semester Spanish students at CMU participated in this study. They practiced using 40 sentences containing between four and 19 words, and between 9 and 31 syllables. During the practice phase, they heard each sentence four times and immediately repeated it back each time. After each repetition, they translated the sentence into English and rated how fluently they were able to repeat the sentence on a scale of 1 to 7.

After the practice phase, they moved on to the test phase, where they heard each sentence and repeated it back one time.

A week later, they came back for a delayed post-test, where they again heard each sentence once and repeated it back.

Hypothesis

We hypothesized that, to answer research question 1, the amount of time the student took to repeat the sentence would decrease. As to question 2, we predicted that students would produce fewer errors. We also predicted that students would be able to significantly rate their accuracy. Study 1 does not address research question 4, since it doesn't involve repeating novel sentences.

Independent Variables

The study was a within-subjects design, with the repetition number as the independent variable. So, we tracked fluency across the four repetitions of each sentence. We also varied the length of the sentences the students heard. The sentences were between four and 19 words, with an average of 8.42 words, and between 9 and 31 syllables, with an average of 15.84 words.

Dependent Variables

In this study, we use three measurements of fluency: pre-speech pause (the amount of time before the student starts speaking), articulation time (the amount of time it takes the student to say the sentence from start to finish) and the number and type of errors and corrections the students make.

Results

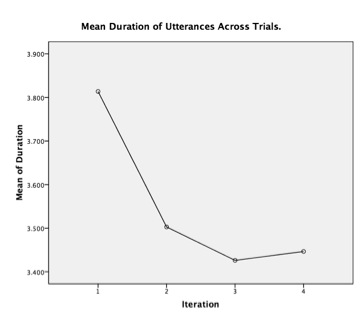

First, we discovered a linear relationship between the trial number (1 through 4) and the duration of the utterance (F=4.318, p=0.038). We measured this by looking both at the time between when they started speaking to when they completed the repetition, and in the initial pause, the time between when the audio stimulus ended and they started speaking. The initial pause, the amount of time before the participant started to repeat the sentence after hearing it, decreased significantly as well (F=3.204, p = 0.023).

We also discovered that across attempts, the number of correctly repeated sentences increased, and the number of incomplete sentences (ones they could not successfully repeat) decreased significantly. We also found that across attempts participants had significantly fewer missing words and different wordings (where the repetition kept the same meaning as the original but with different wording). Doing a trends analysis, we also found significant linear relationships for the number of repetitions/corrections and wrong article usages. However, contrary to what we expected, we found that in both of these cases the number of repetitions/corrections and wrong articles actually increased across attempts.

We also wanted to determine the extent to which students are aware of their own speech and whether they are able to accurately rate their own performance. To determine this, we looked at whether the time taken to repeat the sentence and a number of different errors correlated with their rating of their own speech. First we looked at the duration of the utterance, and found a significant correlation, with a rating of 3 having the longest mean duration of utterance and 7 having the lowest. Ratings of 1 and 2 had shorter durations, because ratings of 1 and 2 generally indicated that they were unable to repeat the sentence, leading to shorter, incomplete sentences. Second, we looked at whether students who rated their proficiency as being higher made fewer errors in their speech. We found that a) students who failed to complete the sentence could reliably rate their performance as a 1 or 2, and b) students with fewer errors rated their performance as higher than those who made more errors. This finding held true for all types of errors except grammatical gender errors. Students did not seem sensitive to grammatical gender errors, and were not more likely to rate their performance as lower.

Explanation

Study Two

In Study Two, in addition to hearing the sentence spoken aloud, students also see pictures that depict the sentence they hear. This way, in the training phase they both see pictures and hear the sentence they repeat, but in the testing phase they can produce the sentences without hearing them ahead of time. This ensures that their speech is not relying on echoic memory, but actually requires them to retrieve lexical and morphological information as they speak.

Students receive training on two constructions: the subjunctive (ex. "Yo dudo que tu estudies"- "I doubt that you are studying") and the preterit/imperfect contrast (ex. "Ayer/De joven tu conduciste/conducías un carro y yo saqué/sacaba fotos. - "Yesterday/As a child you drove/drove a car and I took/took pictures"). Neither of these constructions exist in English- the subjunctive case is not marked and there is no distinction between the preterit and imperfect past tense. Furthermore, both of these constructions contain two phrases, which can be trained either as one whole unit, or broken up into two separate units.

Study Two will further investigate whether it is more effective to train students using the sentence as a whole unit, or through separate phrases. For example, in the subjunctive sentences, students will either be trained on the whole thing, or on two separate phrases, "Yo dudo que-" and "que tu estudies". Doing this may potentially increase learning for two reasons: first, breaking the sentence into pieces will lower working memory constraints, increasing performance on the task; and second, using pieces may decrease cognitive load, thus freeing up more resources for learning.

Study Two involves three phases: the Practice phase, the Immediate Post-test, and the Delayed Post-test. During the training phase, they will see pictures and hear a sentence that that describes those pictures. They will have six blocks of training, three in each construction, each consisting of 7 sentences (or 14 phrases in the Phrase condition). After the training, they move on to the Immediate Post-test phase, where they see pictures and create the sentences without hearing them first. The test phase consists of 42 sentences, 21 they had practiced during the training phase and 21 novel sentences, presented in random order. The Delayed Post-test is exactly like the Immediate Post-test, but in a different order.

Hypotheses

1. Practice: Does one practice condition lead to more improvement in fluency (in terms of correct usage and lower duration/initial pause?)

2. Test: Does one practice condition help learner to produce similar sentences more fluently when they are producing the sentences on their own?

3. Robustness: Does the practice have long-term effects on learners’ oral production?

4. Generalizeability: Is improvement limited to specific practiced sentences, or can the learners generalize to novel, similar sentences?

Independent Variables

Using two constructions will, to a certain extent, allow a within-subjects design. Each participant will receive training in one condition on one sentence construction, and in the other on the other construction.

There are two conditions: the Phrase condition and the Sentence condition. In the Sentence condition, learners will practice the sentences as a whole; in the Phrase condition, the sentences are split into two phrases which are practiced separately.

While it is possible to compare the two conditions as a within-subjects design, the two sentences are very different in nature, and lead to a very different pattern of results. So, in reporting the results we will treat each sentence construction as a separate experiment.

Dependent Variables

The dependent variables in this sentence are the same as in Study One: we are measuring fluency, in terms of pre-sentence pause, articulation time, and errors. We calculated articulation time (mean duration of utterance) as the time between when the speaker started speaking to when they finished the sentence. In cases where the speaker failed to finish the sentence, we set the duration as 15 seconds, the maximum amount of time alloted for the recording. Since during the practice phase, sentences are intrinsically longer than phrases, we normalized this duration (D) by dividing the learner's D by the native speaker's duration, allowing us to look at the duration as a ratio (D-ratio). So, the learner's production is more native-like when the value is close to 1; the greater the D-ratio, the more time the learner took compared to the native speaker, and the less native-like the repetition.

In addition to looking at the duration, we also looked at the initial pause (IP), the amount of time the learner took before he or she began speaking. This may be an indication of pre-speech planning; thus, the longer the speaker waits before he or she starts speaking, the more time he or she needed to process and formulate the sentence. Thus, more native-like performance will have a shorter IP.

Finally, we looked at the number of errors, repetitions, and corrections the learners made as they repeated the sentences. We counted a repetition as the learner repeating a phoneme, word, or phrase without correcting previous speech, and a correction as a repetition that made a correction on a previous utterance. We also coded the errors according to the type of error made. However, for the purposes of analysis, we will lump all errors together. For the purposes of this analysis, we will look at uncorrected errors per sentence, which is the total number of errors minus corrections.

Results

Practice

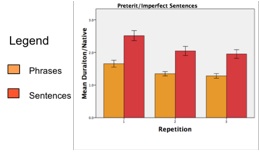

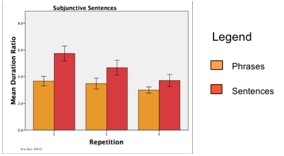

Our first question was whether participants improved across the practice trials, and whether one condition led to more improvement or more native-like repetition. For our measurement of temporal fluency, the D-ratio, we found significant differences for repetition (F = 39.311, p<0.01), with the third repetition taking significantly less time than the 3rd, and condition (F = 258.821, p<0.02), where the phrase condition improves less than the sentence condition. We found similar patterns of results for initial pause and uncorrected as well. Figures 1 and 2 show D-Ratios across trials for both preterit/imperfect and subjunctive sentences across conditions.

Figure 1: D-Ratio for preterit/imperfect sentences across practice trials.

Figure 2: D-Ratio for subjunctive sentences across practice trials.

Note that, while there is less improvement in the phrase condition, production is more native-like in this condition (that is, the D-Ratio is closer to 1). So, while the Phrase condition leads to less improvement, it allows for more native-like improvement.

Test

Next, we want to see whether the type of training makes a difference during the test phase, when they are producing the sentences on their own. Here, we found a different pattern of results based on the type of sentence.

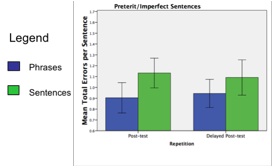

For preterit/imperfect sentences, people who practiced in the Sentence condition had significantly shorter durations, shorter IPs and fewer errors than the Phrase condition. This is especially true at the delayed post-test, though there are no significant differences between immediate and delayed post-test for either condition.

Figure 3: Mean number of errors per sentence for preterit/imperfect sentences at immediate and delayed post-tests.

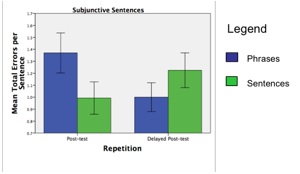

However, for subjunctive sentences there is a different pattern of results. For these sentences, which are shorter but more complex, while the sentence condition does better than the Phrase condition during the immediate post-test, at the delayed post-test, the Phrase condition does significantly better. In fact, the Phrase condition improves significantly by the delayed post-test, while the Sentence condition gets significantly worse.

Figure 4: Mean number of errors per sentence for subjunctive sentences at immediate and delayed post-tests.

Robustness

Next, we wanted to see whether the training had any long-term effects. Looking at the results of the 2 (Repetition) by 2 (Condition) univariate ANOVA performed in the Test section, we can see that the long-term effects vary by sentence type.

For the preterit/imperfect sentences (Figure 3), we can see no significant main effect of Repetition, and no interaction of Repetition and Condition. So, for these sentences, it appears that whatever effects of the training there are, they are still present a week later.

However, for the subjunctive sentences (Figure 4) there is a rather interesting interaction. As mentioned in the above section, the Phrase condition performs significantly worse at the immediate post-test, but improves by the delayed post-test, while the Sentence condition sees significant decay between the immediate and delayed post-test. So, while the Phrase condition appears to lead to long-term improvements, the Sentence condition does not.

Generalizeability

Finally, we wanted to see whether the training led to generalizeable learning, or whether the training simply allowed students to improve vocalization of the sentences on which they had been trained. To do this, we did a one-way ANOVA for Novelty (novel or trained). We found a significant effect of novelty for both duration of utterance (F = 14.571, p<0.01) and number of errors per sentence (F = 4.306, p = 0.038), with novel sentences taking longer to produce and containing more errors than trained sentences. However, a two (Condition) by two (Novelty) ANOVA found no interaction between Condition and Novelty, showing that neither condition seemed to lead to more generalizeable learning.

Study 3

Study 3 serves first to investigate the differences between different speech elicitation methods. We are first comparing the picture task used in Study 2 to the oral repetition task used in Study 1, while also incorporating a pre- and post-test with multiple testing methods as well as working memory span tasks and individual differences tasks to a) further investigate the use of oral repetition in developing second language fluency and b) see whether using pictures adds anything to the oral repetition task.

Study 3 also includes a series of pre- and post-tests. This will allow us to determine a) whether participants are actually improving and b) what skills are being training by the tasks.

Independent Variables

This study has two conditions: Picture training and Repetition training. Picture training is identical to Study 2: they see pictures and hear a sentence that describes those pictures, then repeat it back. They hear each sentence and repeat it four times. Repetition training is identical to Picture training, but they do not see the pictures while they hear the sentence.

As in Study 2, this study uses a within-subjects design, where all participants receive both kinds of training. However, rather than splitting up the training by sentence type, it is split up by verb. So, participants will receive Picture training with one set of verbs, and Repetition training on another set. They will be tested on both sets of verbs, as well as a third set that was not trained, which serves as a control.

Dependent Variables

Just like in Study 2, we are looking at temporal measures of fluency, including Initial Pause (IP) and Length of Duration (LD). We are also using a coding scheme almost identical to Study 2 to code repetitions, corrections, and grammatical errors. We will look for changes in temporal and accuracy measures of fluency during both training and testing phases.

Test Measures

One of the major additions of this study is a series of three test measures that can tap into the different aspects of sentence production. This is different from previous studies in that a) the participants receive both pre- and immediate and delayed post-tests, allowing for comparison before and after training, and b) participants are tested on tasks on which they did not specifically receive training. Below are descriptions of the three tasks they receive:

- Repetition This test is identical to the repetition training task: they hear a sentence and repeat it. This will test to see whether they improve simply in their ability to repeat back sentences they hear. It may be the case that successful performance on this task requires lexical retrieval and morphosyntactic processing. However, if participants' performance increases only on this task and not on other tasks that do require extensive processing, it may be the case that participants are only improving on more surface-level sound production.

- Word Combination In this test, participants see a series of words displayed on the screen and combine those words to create a sentence. There are three words groups: The Cue at the top of the screen, which indicates what tense the sentence should be in (e.g., "Si", "Ayer", etc.), Subj1/Verb1 on the left hand side, which gives the subject and verb of the first half of the sentence, and Subj2/Verb2 on the right hand side, which gives the subject and verb for the second half of the sentence. For example, if they see the word "Si" at the top of the screen, "yo/cocinar la cena" on the left side and "tu/lavar los platos" on the right side, they would create the sentence "Si yo cocino la cena, tu lavarás los platos." As this task removes the need for lexical retrieval, this task will measure whether training led to improvements on using the cues to determine verb tense and conjugate verbs quickly.

- Translation In this test, participants see a sentence in English and translate it to Spanish. For example, if they see the sentence "Yesterday, we went fishing and you took pictures.", they would say "Ayer nosotros fuimos de pesca y tu sacaste fotos." This task, unlike the Word Combination task, involves both lexical retrieval (through translation) and morphosyntactic processing.

Results

Thus far, we have analyzed data on the accuracy of sentences produced during the test phase, on the Translate, Word, and Repetition tasks. We analyzed this by coding each part of the sentence (Cue, Noun 1, Verb 1, Noun 2, and Verb 2) and marking them as correct or incorrect. Since we are focused primarily on the acquisition of morphosyntactic information, we will limit our reporting to the accuracy of the Verbs.

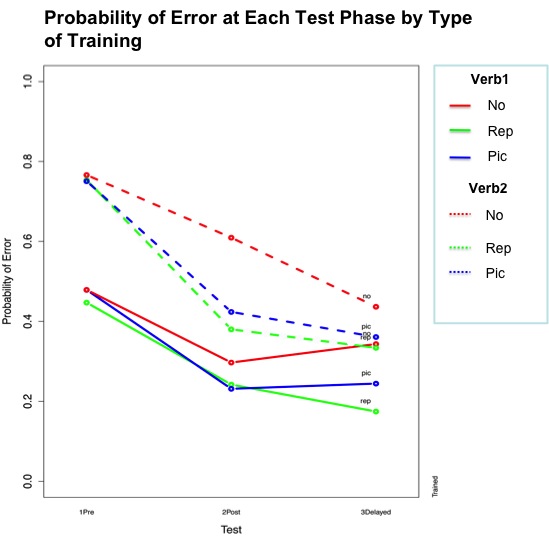

We performed a mixed ANCOVA, with Subject and Sentence as random variables and test (Pre, Post, and Delayed), training condition (Repetition, Picture, and No Training) and task type (Word, Translate, and Repetition) as factors.

First, we compared performance at each test by the training condition for the verb. The results are summarized in Figure 5. We found that for both Verb 1 and 2, accuracy increased significantly from Pre to Post test (p<0.001). Furthermore, there was a significant interaction between Training and Test, with the increase being largest for Rep and Pic training conditions (that is, on verbs that were trained). The result is that, for both Post and Delayed tests, the No Training condition was significantly worse than the Pic and Rep conditions, though there was no significant difference between the Training and No Training conditions.

We found the same pattern of results for Verb 2: Performance overall was worse for Verb 2, which may be due to the time pressure and the fact that they do not have enough time to produce the second phrase. However, verbs in all conditions were significantly more accurate at Post and Delayed, with a significant interaction of Condition.

Study 4

For Study 4, we investigated the use of the Oral Repetition Task with novice learners of German. We first wanted to know whether the speaking component of this task was crucial for the acquisition of speaking skills or acquisition of the morphosyntactic information used in these sentences. Second, we wanted to know whether participants would achieve more, in terms of fluency or accuracy, if they were first presented with the vocabulary before they were asked to produce full sentences, as opposed to beginning immediately to be presented with short, subject-verb phrases.

To determine this we ran two versions of a training study; in Study 1a, we provided participants with the oral repetition task training, where they listened to sentences and repeated them back. Study 1b was the same as Study 1a except, during the Oral Repetition parts of the study, participants only listened to the response from a selected participant from Study 1a.

Each study was a two-session training study with a delayed post-test. On the first day, participants were trained on simple two-word sentences consisting of a subject and a verb (i.e., “Der Mann trinkt”, or The man drinks). This session consists of two grammar lessons, one on German articles (der, die, and das) and one on conjugating German verbs, a Receptive Test block, and a Productive Test block, consisting of the Oral Repetition Task and the Word, Repetition, and Translate tasks used in the previous study. On the second day, they are trained on slightly longer sentences consisting of a subject, verb, and clothing-related object (i.e., “Der Mann hat die Hose”, or The man has the pants.). This session has a review of German articles and a brief lesson on the use of articles used with direct objects, followed by a Receptive Test block, and the Productive Test block, just like in Session 1. A week later, participants came back in for a Delayed Post-test, consisting of test items from the first and second session.

This study had two conditions: the Vocabulary condition, where each session started with a block of training on particular words, and the Phrase condition, where they were immediately presented with sentences.

Study 1a was conducted in the Summer of 2011. The participants’ speech from this study were then used to act as input for the participants of Study 1b, which is currently being conducted as of Summer 2012. Our summer intern is working on this as her major project, so we hope to have results of Studies 1a and 1b by the end of the summer.

References

Levelt, W. J. M. (1989). Speaking. Boston: MIT Press.

Yoshimura, Y., & MacWhinney, B. (2007). The effect of oral repetition on L2 speech fluency: an experimental tool and language tutor. Paper presented at the Speech and Language Technology in Education, The Summit Inn, Farmington, PA.