Difference between revisions of "Hausmann Study"

(→Annotated bibliography) |

(→Abstract) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

== A comparison of self-explanation to instructional explanation == | == A comparison of self-explanation to instructional explanation == | ||

''Robert Hausmann and Kurt VanLehn'' | ''Robert Hausmann and Kurt VanLehn'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Summary Table === | ||

| + | {| border="1" cellspacing="0" cellpadding="5" style="text-align: left;" | ||

| + | | '''PIs''' || Robert G.M. Hausmann & Kurt VanLehn | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | '''Other Contributers'''<br>* '''Faculty: '''<br>* '''Staff: ''' | ||

| + | | <br>Donald J. Treacy (USNA), Robert N. Shelby (USNA)<br>Brett van de Sande (Pitt), Anders Weinstein (Pitt) | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | '''Study Start Date''' || Sept. 1, 2005 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | '''Study End Date''' || Aug. 31, 2006 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | '''LearnLab Site''' || Physics II | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | '''LearnLab Course''' || Physics | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | '''Number of Students''' || ''N'' = 104 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | '''Total Participant Hours''' || 190 hrs. | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | '''DataShop''' || Target date: April 30, 2007 | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | <br> | ||

=== Abstract === | === Abstract === | ||

Revision as of 17:02, 29 March 2007

A comparison of self-explanation to instructional explanation

Robert Hausmann and Kurt VanLehn

Summary Table

| PIs | Robert G.M. Hausmann & Kurt VanLehn |

| Other Contributers * Faculty: * Staff: |

Donald J. Treacy (USNA), Robert N. Shelby (USNA) Brett van de Sande (Pitt), Anders Weinstein (Pitt) |

| Study Start Date | Sept. 1, 2005 |

| Study End Date | Aug. 31, 2006 |

| LearnLab Site | Physics II |

| LearnLab Course | Physics |

| Number of Students | N = 104 |

| Total Participant Hours | 190 hrs. |

| DataShop | Target date: April 30, 2007 |

Abstract

This in vivo experiment compared the learning that results from either hearing an explanation (instructional explanation) or generating it oneself (self-explanation). Students studied a physics examples, which were presented step by step. For half the students, the example steps were incompletely justified (i.e., the explanations connecting some steps were missing) whereas for the other half, the example steps were completely justified. Crossed with this variable was an attempted manipulation of the student’s studying strategy. Half the students were instructed and prompted to self-explain at the end of each step, while the other half were prompted to paraphrase it (click the following link for screen shots of each experimental condition). Paraphrasing was selected as the contrasting study strategy because earlier work has shown that paraphrasing suppresses self-explanation.

Of the four conditions, one condition was key to testing our hypothesis: the condition where students viewed completely justified examples and were asked to paraphrase them. If the learning gains from this condition had been just as high as those from conditions were self-explanation was encouraged, then instructional explanation would have been just as effective as self-explanation. On the other hand, if the learning gains were just as low as those where instructional explanations were absent and self-explanation was suppressed via paraphrasing, then instructional explanation would have been just as ineffective as no explanation at all.

Preliminary results of the normal and robust learning measures suggest that the latter case occurred, so instructional explanation were not as effective as self-explanations.

Background and Significance

The first studies of self-explanation, which were based on analysis of verbal protocols, showed that the amount of self-explaining correlated strongly with performance on post-test measures of problem-solving performance (Bielaczyc, Pirolli, & Brown, 1995; Chi, Bassok, Lewis, Reimann, & Glaser, 1989; Renkl, 1997). Because these studies compared self-explanation to the lack of any explanation at all, there is a confound between the generative act or producing the explanations and the additional content of the explanations themselves. Perhaps if students were simply given these explanations, they would learn just as much. Alternatively, learning from self-explaining might arise from the activity of producing the explanations. Thus, if they were given the explanations, they would not learn just as much. In other words, is it merely attending to the explanations that matters, or is robust learning more likely to occur if students generate the explanations themselves? Let us label these hypotheses as follows:

- The Attention Hypothesis: learning from self-generated explanations should produce comparable learning gains as author-provided explanation, provided the learner pays attention to them. Both self-generated and author-provided explanations should exhibit better learning than no explanation.

- The Generation Hypothesis: learning from self-generated explanations should produce greater learning gains than author-provided explanations because they are produced from the students’ own background knowledge; however, author-provided explanations should be comparable to no explanation.

There have only been a few empirical studies that attempt to separate the Attention hypothesis from the Generation hypothesis (Brown & Kane, 1988; Schworm & Renkl, 2002). An exemplary case can be found in a study by Lovett (1992) in the domain of permutation and combination problems. Lovett crossed the source of the solution (subject vs. experimenter) with the source of the explanation for the solution (subject vs. experimenter). For our purposes, only two of the experimental conditions matter. The experimenter-subject condition was analogous to experimental materials found in a self-explanation experiment wherein the students self-explained an author’s solution, whereas in the experimenter-experimenter condition, the students studied an author-provided explanation. Lovett found that the experimenter-experimenter condition demonstrated better performance, especially on far-transfer items. Lovett’s interpretation was that the experimenter-experimenter condition was effective because it contained higher quality explanations than those generated by students. Consistent with this interpretation, when Lovett analyzed the protocol data, she found that the participants who generated the key inferences had the same learning gains as participants who read the corresponding inferences. Thus, of our two hypotheses, Lovett’s experiment supports the Attention hypothesis: the content of self-explanations matters, while the source of the explanation does not.

Brown and Kane (1988) found that children’s explanations, generated either spontaneously or in response to prompting, were much more effective at promoting transfer than those provided by the experimenter. In particular, students were first told a story about mimicry. Some students were then told, "Some animals try to look like a scary animal so they won’t get eaten.” Other students were asked first, “Why would a furry caterpillar want to look like a snake?” and if that did not elicit an explanation, they were asked, "What could the furry caterpillar do to stop the big birds from eating him?" Most students got the question right, and if they did, 85% were able to answer a similar question about two new stories. If they were told the rule, then only 45% were able to answer a similar question about the new stories. This result is consistent with the Generation hypothesis, which is that an explanation is effective when the student generates it. However, the students who were told the rule may not have paid much attention to it, according to Brown and Kane.

In summary, one study’s results are consistent with the Attention hypothesis, and the other study’s results are consistent with the Generation hypothesis, but both studies confounded two variables. In the Lovett study, the student-produced and author-provided explanations were of different qualities. In the Brown and Kane study, the students in the author-provided explanations condition may not have paid much attention to the explanations.

Glossary

Research question

How is robust learning affected by self-explanation vs. instructional explanation?

Independent variables

Two variables were crossed:

- Did the example present an explanation with each step or present just the step?

- After each step (and its explanation, if any) was presented, students were prompted to either further explain the step or paraphrase the step in their own words.

The condition where explanations were presented in the example and students were asked to paraphrase them is considered the “instructional explanation” condition. The two conditions where students were asked to self-explain the example lines are considered the “self-explanation” conditions. The remaining condition, where students were asked to paraphrase examples that did not contain explanations, was considered the “no explanation” condition. Note, however, that nothing prevents a student in the paraphrasing condition to self-explain (and vice-versa).

Hypothesis

For these well-prepared students, self-explanation should not be too difficult. That is, the instruction should be below the students’ zone of proximal development. Thus, the learning-by-doing path (self-explanation) should elicit more robust learning than the alternative path (instructional explanation) wherein the student does less work.

As a manipulation check on the utility of the explanations in the complete examples, we hypothesize that the instructional explanation condition should produce more robust learning than the no-explanation condition.

Dependent variables

- Normal post-test

- Near transfer, immediate: During training, examples alternated with problems, and the problems were solved using Andes. Each problem was similar to the example that preceded it, so performance on it is a measure of normal learning (near transfer, immediate testing). The log data were analyzed and assistance scores (sum of errors and help requests, normalized by the number of transactions) were calculated.

- Robust learning

- Near transfer, retention: On the student’s regular mid-term exam, one problem was similar to the training. Since this exam occurred a week after the training, and the training took place in just under 2 hours, the student’s performance on this problem is considered a test of retention.

- Near and far transfer: After training, students did their regular homework problems using Andes. Students did them whenever they wanted, but most completed them just before the exam. The homework problems were divided based on similarity to the training problems, and assistance scores were calculated.

- Accelerated future learning: The training was on electrical fields, and it was followed in the course by a unit on magnetic fields. Log data from the magnetic field homework was analyzed as a measure of acceleration of future learning.

Results

- Normal post-test

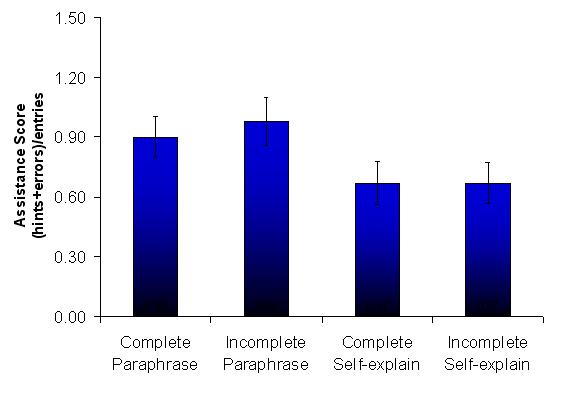

- Near transfer, immediate: The self-explanation condition demonstrating lower normalized assistance scores than the paraphrase condition, F(1, 73) = 6.19, p = .02, ηp2 =.08.

- Near transfer, immediate: The self-explanation condition demonstrating lower normalized assistance scores than the paraphrase condition, F(1, 73) = 6.19, p = .02, ηp2 =.08.

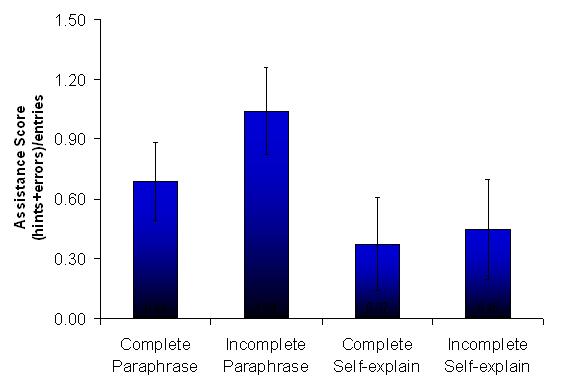

- Robust learning

- Near transfer, retention: Results on the measure were mixed. While there were no reliable main effects or interactions, the complete self-explanation group was marginally higher than the complete paraphrase condition (LSD, p = .06). Moreover, we analyzed the students’ performance on a homework problem that was isomorphic to the chapter exam in that they shared an identical deep structure (i.e., both analyzed the motion of a charged particle moving in two dimensions). The self-explanation had reliably lower normalized assistance scores than the paraphrase condition, F(1, 27) = 4.07, p = .05, ηp2 = .13.

- Near and far transfer:

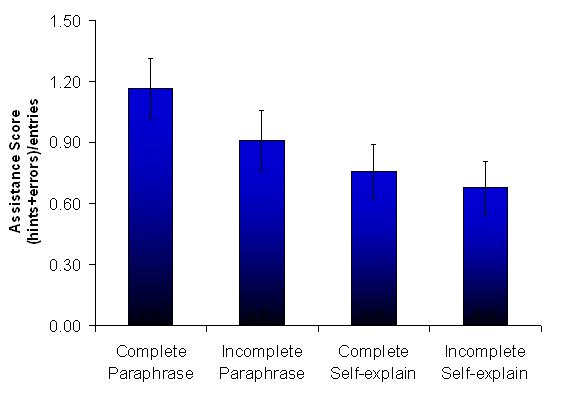

- Accelerated future learning: There was no effect for example completeness; however, the self-explanation condition demonstrating lower normalized assistance scores than the paraphrase condition, F(1, 46) = 5.22, p = .03, ηp2 = .10.

- Near transfer, retention: Results on the measure were mixed. While there were no reliable main effects or interactions, the complete self-explanation group was marginally higher than the complete paraphrase condition (LSD, p = .06). Moreover, we analyzed the students’ performance on a homework problem that was isomorphic to the chapter exam in that they shared an identical deep structure (i.e., both analyzed the motion of a charged particle moving in two dimensions). The self-explanation had reliably lower normalized assistance scores than the paraphrase condition, F(1, 27) = 4.07, p = .05, ηp2 = .13.

Explanation

This study is part of the Interactive Communication cluster, and its hypothesis is a specialization of the IC cluster’s central hypothesis. The IC cluster’s hypothesis is that robust learning occurs when two conditions are met:

- The learning event space should have paths that are mostly learning-by-doing along with alternative paths where a second agent does most of the work. In this study, self-explanation comprises the learning-by-doing path and instructional explanations are ones where another agent (the author of the text) has done most of the work.

- The student takes the learning-by-doing path unless it becomes too difficult. This study tried (successfully, it appears) to control the student’s path choice. It showed that when students take the learning-by-doing path, they learned more than when they took the alternative path.

The IC cluster’s hypothesis actually predicts an attribute-treatment interaction (ATI) here. If some students were under-prepared and thus would find the self-explanation path too difficult, then those students would learn more on the instructional-explanation path. ATI analyzes have not yet been completed.

Annotated bibliography

- Presentation to the PSLC Advisory Board, December, 2006 [1]

- Presentation to the NSF Follow-up Site Visitors, September, 2006

- Preliminary results were presented to the Intelligent Tutoring in Serious Games workshop, Aug. 2006 [2]

- Presentation to the NSF Site Visitors, June, 2006

- Poster presented at the annual meeting of the Science of Learning Centers, Oct. 2006.

- Symposium accepted to EARLI 2007

- Symposium accepted at AERA 2007

- Full-paper accepted at AIED 2007

- Full-paper submitted to CogSci 2007

References

- Anzai, Y., & Simon, H. A. (1979). The theory of learning by doing. Psychological Review, 86(2), 124-140.

- Chi, M. T. H., Bassok, M., Lewis, M. W., Reimann, P., & Glaser, R. (1989). Self-explanations: How students study and use examples in learning to solve problems. Cognitive Science, 13, 145-182. [3]

- Hausmann, R. G. M., & Chi, M. T. H. (2002). Can a computer interface support self-explaining? Cognitive Technology, 7(1), 4-14. [4]

- Lovett, M. C. (1992). Learning by problem solving versus by examples: The benefits of generating and receiving information. Proceedings of the Fourteenth Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society (pp. 956-961). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Schworm, S., & Renkl, A. (2002). Learning by solved example problems: Instructional explanations reduce self-explanation activity. In W. D. Gray & C. D. Schunn (Eds.), Proceedings of the 24th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society (pp. 816-821). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.[5]

Connections

This project shares features with the following research projects: