Difference between revisions of "Visual Feature Focus in Geometry: Instructional Support for Visual Coordination During Learning (Butcher & Aleven)"

(→Research questions) |

(→Future Plans) |

||

| (15 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 65: | Line 65: | ||

=== Research questions === | === Research questions === | ||

''Study 1: Does coordinated visual-verbal training on geometry concepts prior to problem solving support learning?'' | ''Study 1: Does coordinated visual-verbal training on geometry concepts prior to problem solving support learning?'' | ||

| − | |||

This in vivo student extends our understanding of coordinative learning by addressing whether concept learning can be supported by visual-verbal coordination before problem solving practice. This study was conducted at Riverview High School, in Winter 2007-2008 (testing ended in January 2008). In a two condition study, we varied the type of conceptual training that students receive before beginning problem solving activities. | This in vivo student extends our understanding of coordinative learning by addressing whether concept learning can be supported by visual-verbal coordination before problem solving practice. This study was conducted at Riverview High School, in Winter 2007-2008 (testing ended in January 2008). In a two condition study, we varied the type of conceptual training that students receive before beginning problem solving activities. | ||

<b>Study 1: Independent Variables</b><br> | <b>Study 1: Independent Variables</b><br> | ||

| − | + | [[Image:VisualOnlyTraining.jpg]] | |

| − | [[Image:VisualOnlyTraining. | + | <br> |

| − | + | [[Image:VisualVerbalTraining.jpg]] | |

| − | < | + | <br> |

| − | [[Image:VisualVerbalTraining. | ||

''Study 2: How does coordination of visual and verbal information sources support visual feature understanding and application?'' | ''Study 2: How does coordination of visual and verbal information sources support visual feature understanding and application?'' | ||

| + | This in vivo study extends our understanding of coordinative learning by addressing whether visual-verbal coordination maximizes robust learning when coordination is tied to student errors during problem solving. This study was conducted at CWCTC, beginning in late January 2008. The study curriculum was the Angles units of the Geometry Cognitive Tutor. In a 3 condition study, we varied the coordinative learning activities following student errors in the tutor. | ||

| − | + | <b>Study 2: Independent Variables</b><br> | |

| + | <i><b>No Highlighting</b></i>: Following an error, no highlighting in the visual diagram is provided to students.<br> | ||

| + | [[Image:NoHighlight.jpg]]<br><br> | ||

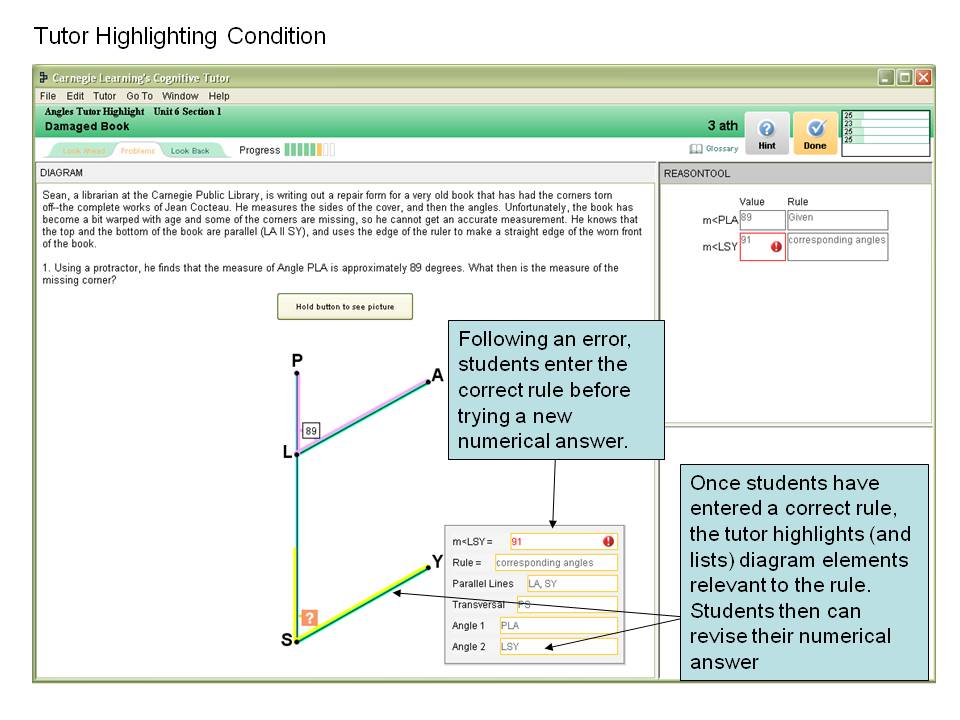

| + | <i><b>Tutor Highlighting</b></i>: Following an error, the tutor highlighted the features of the problem diagram that are relevant to the selected geometry principle. | ||

| + | [[Image:TutorHighlight.jpg]]<br><br> | ||

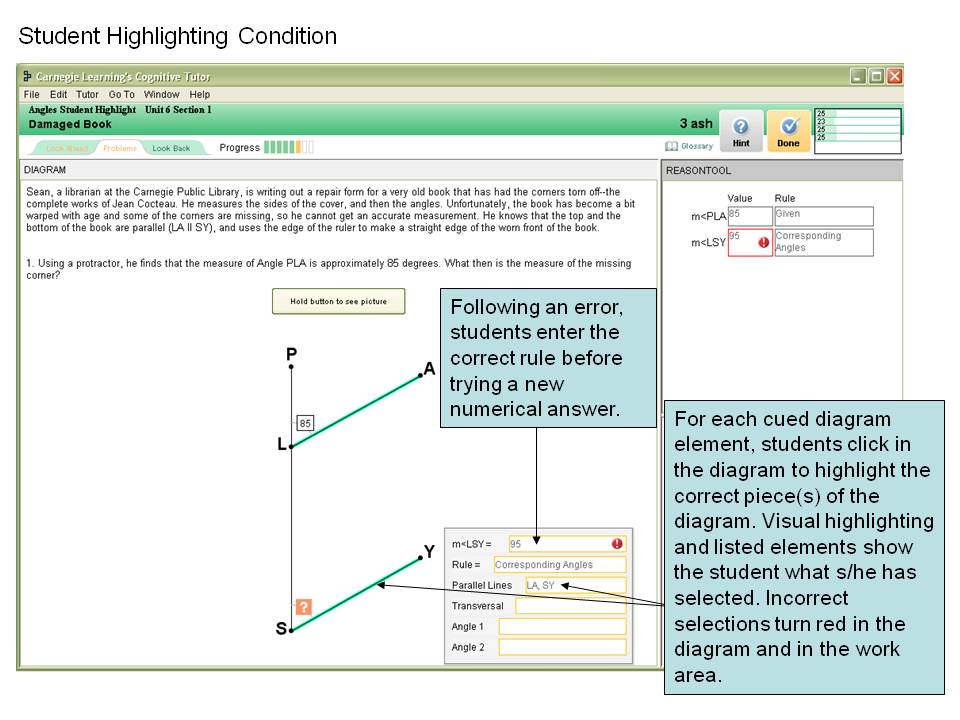

| + | <i><b>Student Highlighting</b></i>: Following an error, the student is required to highlight the relevant visual information associated with geometry principles (namely, the features in the diagram to which the selected rule applies). | ||

| + | [[Image:StudentHighlight.jpg]] | ||

| − | === | + | === Results === |

''Study 1'' | ''Study 1'' | ||

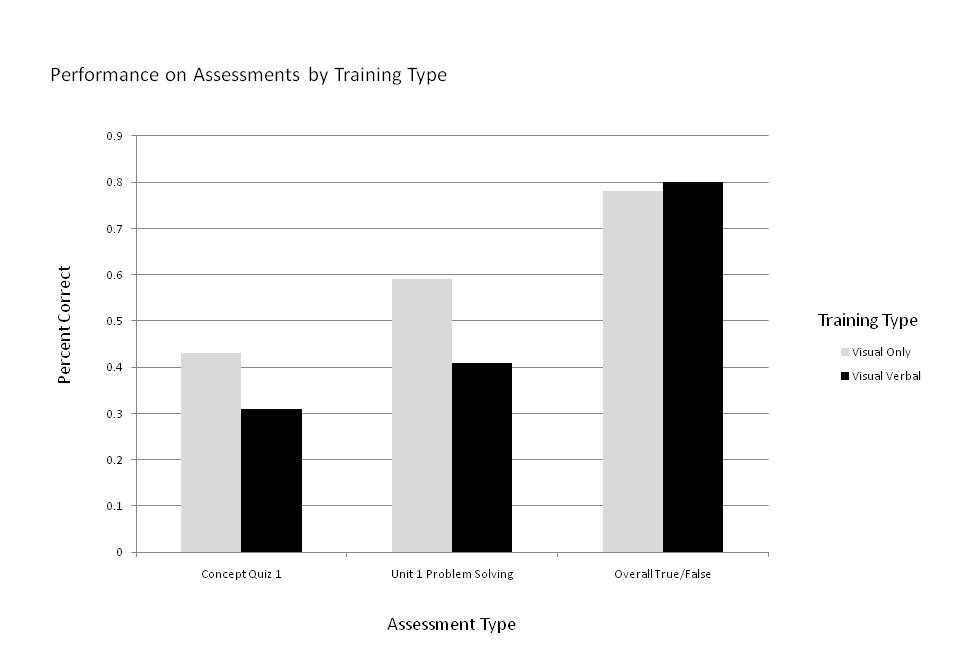

| − | + | Although we hypothesized that coordinative support in linking verbal definitions of geometry concepts to visual examples would support the development of robust knowledge, visual only training was found to be as effective as coordinated visual-verbal training in this study. During early use of the tutor (as seen in the Concept Quiz 1 and Unit 1 Problem Solving results), the pattern of results showed an advantage for students trained in the visual-only condition. However, by posttest (see Overall True/False in the graph), students performed similarly on knowledge assessments.<br> | |

| + | [[Image:VisVerbTrainingResults.jpg]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

''Study 2'' | ''Study 2'' | ||

| − | We | + | We hypothesized that active [[coordination]] -- where students highlight relevant diagram elements following problem-solving errors -- would best support [[robust learning]]. Although tutor highlighting was hypothesized to be better than the no highlighting (control) condition, we expected that visual-verbal coordination would be best supported by student interaction with diagrams. |

| + | |||

| + | Overall, student progress was slower than anticipated by the experimenters or the classroom teacher. Of the 83 students working in the intelligent tutor, 31 students (11 Control, 10 Visual Highlighting, 10 Visual Cueing) reached the last instructional unit (unit 3) during the experiment. For these students, results show that benefits of visual self-explanation for problem solving change over the course of tutoring practice (see the figure below). | ||

| + | In the first instructional unit, students provided with visual cueing by the tutor are most accurate in their problem solving answers (M = .89, SD = .05) compared to students in the control condition (M = .83, SD = .06) or the visual-explanation condition (M = .85, SD = .05). Results demonstrated an overall effect of condition (F (2, 27) = 4.01, p = .03); post-hoc Bonferroni comparisons demonstrated that visual cueing significantly outperformed the control condition (p = .03) but not the visual self-explanation condition (p = .15), which fell between the two other groups. In contrast, by unit 3, students who visually self-explained the geometry principles (M = .86, SD = .08) were most accurate in their problem-solving answers, followed by the visual cueing condition (M = .83, SD = .11), and then the control condition (M = .73, p = .10). Results again demonstrated an overall effect of condition (F(2, 27) = 4.84, p = .016); post-hoc Bonferroni comparisons showed that the control condition was outperfomed by the visual self-explanations (p = .03) and the visual cueing (p = .05) conditions. <br><br> | ||

| + | We analyzed overall posttest and delayed posttest results for students who had also taken the pretest. Posttest results demonstrated an overall improvement from pre- to posttest (F(1, 65) = 9.68, p = .03), but no significant condition differences (F<1). At delayed posttest, result suggested a test time (pretest vs. delayed posttest) by condition interaction (F(2. 37) = 2.87, p = .07). At delayed posttest (see Figure 2), students in the visual self-explanation condition outperformed students from the visual cueing condition and the control (interactive diagram) condition. <br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:EarliGraph.jpg]] | ||

=== Explanation === | === Explanation === | ||

| Line 99: | Line 113: | ||

*Butcher, K. R., & Aleven, V. (2007). Integrating visual and verbal knowledge during classroom learning with computer tutors. In D. S. McNamara & J. G. Trafton (Eds.), Proceedings of the 29th Annual Cognitive Science Society (pp. 137-142). Austin, TX: Cognitive Science Society. | *Butcher, K. R., & Aleven, V. (2007). Integrating visual and verbal knowledge during classroom learning with computer tutors. In D. S. McNamara & J. G. Trafton (Eds.), Proceedings of the 29th Annual Cognitive Science Society (pp. 137-142). Austin, TX: Cognitive Science Society. | ||

| + | *Butcher, K. R., & Aleven, V. A. (in press 2009). Visual self-explanation during intelligent tutoring? More than attentional focus? <i>European Association for Research on Learning and Instruction</i>, 13th Biennial Conference. August 25-29, 2009: Amsterdam, the Netherlands. | ||

==== References ==== | ==== References ==== | ||

| Line 106: | Line 121: | ||

====Future Plans==== | ====Future Plans==== | ||

| − | * | + | *August 2009: Symposium presentation at EARLI 2009 |

| − | * | + | *July - September 2009: Prepare article and submit to journal |

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Category:Study]] | [[Category:Study]] | ||

Latest revision as of 00:39, 9 May 2009

Contents

[hide]Visual Feature Focus in Geometry: Instructional Support for Visual Coordination During Learning

Kirsten Butcher & Vincent Aleven

Summary Table

Study 1

| PIs | Kirsten R. Butcher & Vincent Aleven |

| Other Contributers | Research Programmers/Associates: Octav Popescu (Research Programmer, CMU HCII), Thomas Bolster (Research Associate, CMU HCII), Michael Nugent, Research Programmer CMU HCII) |

| Study Start Date | December 2007 |

| Study End Date | February 2008 |

| LearnLab Site | Riverview High School |

| LearnLab Course | Geometry |

| Number of Students | 50 |

| Total Participant Hours | 200 |

| DataShop | Yes. |

Study 2

| PIs | Kirsten R. Butcher & Vincent Aleven |

| Other Contributers | Research Programmers/Associates: Octav Popescu (Research Programmer, CMU HCII), Thomas Bolster (Research Associate, CMU HCII), Michael Nugent, Research Programmer CMU HCII) |

| Study Start Date | January 28, 2008 |

| Study End Date | March 2008 |

| LearnLab Site | Central Westmoreland Career & Technology Center (CWCTC) |

| LearnLab Course | Geometry |

| Number of Students | 83 |

| Total Participant Hours | 415 |

| DataShop | Yes. |

Abstract

Is visual-verbal integration a major source of difficulty for students learning geometry? Further, how can coordinative learning with visual and verbal knowledge components in geometry be supported by instructional events that vary the support for and type of sense making in which learners engage during problem solving? In geometry, students may have difficulty integrating visual and verbal information sources for two reasons: first, they may lack deep understanding of geometry concepts (e.g., what is an interior angle?) that are relevant to problem-solving principles (e.g., the interior angles theorem for circles); second, students may be unable to coordinate visual problem features with verbal principles during problem solving. Our research explores the robust learning effects associated with visual-verbal training of geometry features and varied levels of instructional assistance in coordinating visual diagram features with verbal geometry principles during problem solving.

Background & Significance

Successful Learning is Supported by Coordinated Visual-Verbal Knowledge

Research with both experts and more novice learners has shown that integrated visual-verbal knowledge supports successful problem solving. In geometry, for example, experts use key diagram configurations to cue retrieval of relevant schemas, and these visual configurations help successfully model expert proof (Koedinger & Anderson, 1990). In mathematics, experts are more likely than novices to generate diagrams and to use these visual representations to guide their reasoning about problem-solving steps (Stylianou, 2002).

Even for more novice learners, learning benefits are seen when visual and verbal information is processed jointly instead of in isolation. In geometry, superficial visual similarities between geometry diagrams can decrease a novice’s likelihood of problem-solving success because novices focus on irrelevant visual similarities at the expense of conceptual problem differences (Lovett & Anderson, 1994). Even when visualizations depict helpful (rather than misleading) information for learning, verbal explanations support deeper understanding. For example, the value of graphical feedback when using a physics simulation is greatly enhanced by the presence of short, embedded verbal explanations that focus learners on key principles (Rieber, Tzeng, & Tribble, 2004). Similarly, learners suffer when verbal information is processed alone. Visual representations that are designed to be informationally-equivalent to a given piece of text or audio nevertheless support deeper understanding of the text (Ainsworth & Loizou, 2003; Butcher, 2006) or audio explanations (e.g., Moreno & Mayer, 2002). Further, students benefit from activities that coordinate both visual and verbal sources; these activities include verbal comparison of self-generated and ideal diagrams (Van Meter, 2001; Van Meter, Aleksic, Schwartz, & Garner, 2006) as well as dragging and dropping verbal information into a diagram to create an integrated representation (Bodemer, Ploetzner, Feuerlein, & Spada, 2004).

The potential importance of connecting visual and verbal information also is supported by the literature on knowledge transfer following example learning, where the use of abstract rules can combat problems associated with focus on superficial similarity. Although examples often support problem solving, students frequently are unable to successfully solve transfer problems that are not superficially very similar to the trained examples (for a review, see Reeves & Weissberg, 1994). Research in reasoning and transfer has found that student performance is better supported by examples that include instruction on abstract rules when compared to learning with examples alone or instruction alone (Fong, Krantz, & Nisbett, 1986; Fong & Nisbett, 1991). Thus, we should expect that when students connect geometry diagrams (examples) to relevant geometry principles (abstract rules), robust learning will be supported.

Glossary

Research questions

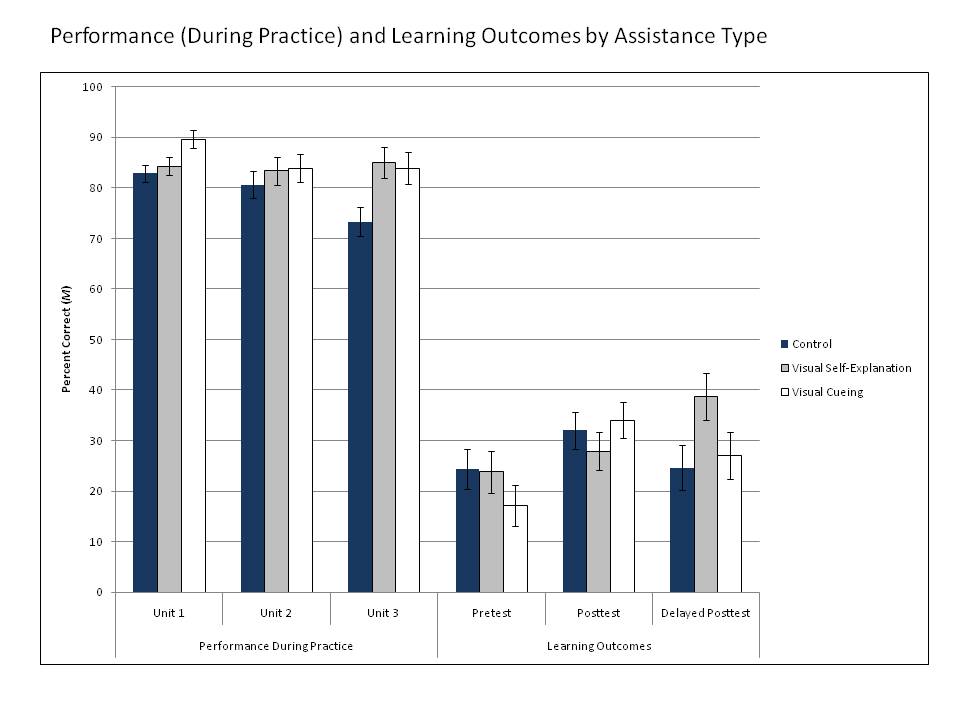

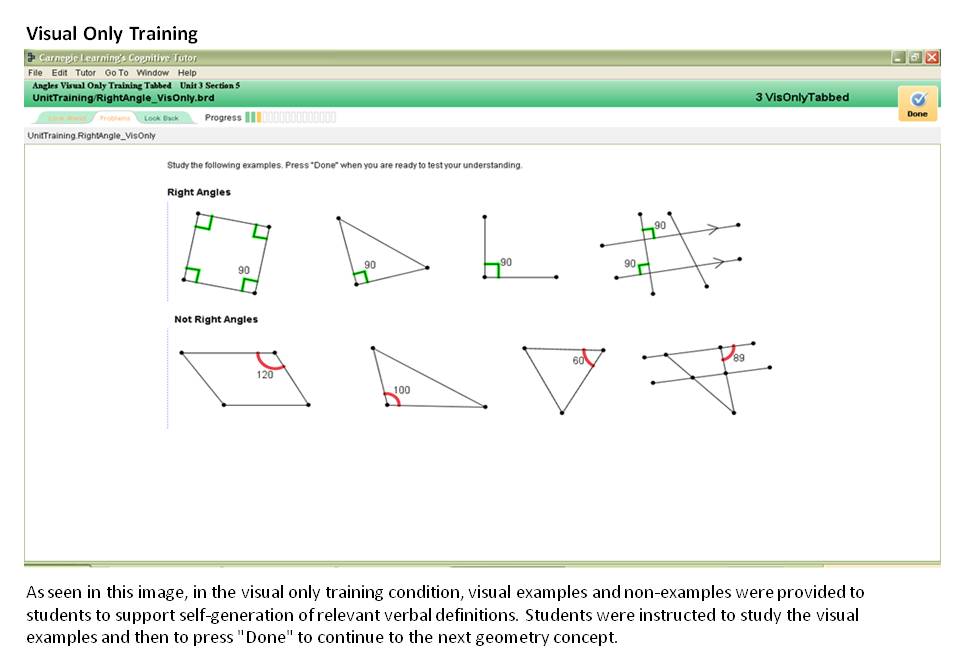

Study 1: Does coordinated visual-verbal training on geometry concepts prior to problem solving support learning? This in vivo student extends our understanding of coordinative learning by addressing whether concept learning can be supported by visual-verbal coordination before problem solving practice. This study was conducted at Riverview High School, in Winter 2007-2008 (testing ended in January 2008). In a two condition study, we varied the type of conceptual training that students receive before beginning problem solving activities.

Study 1: Independent Variables

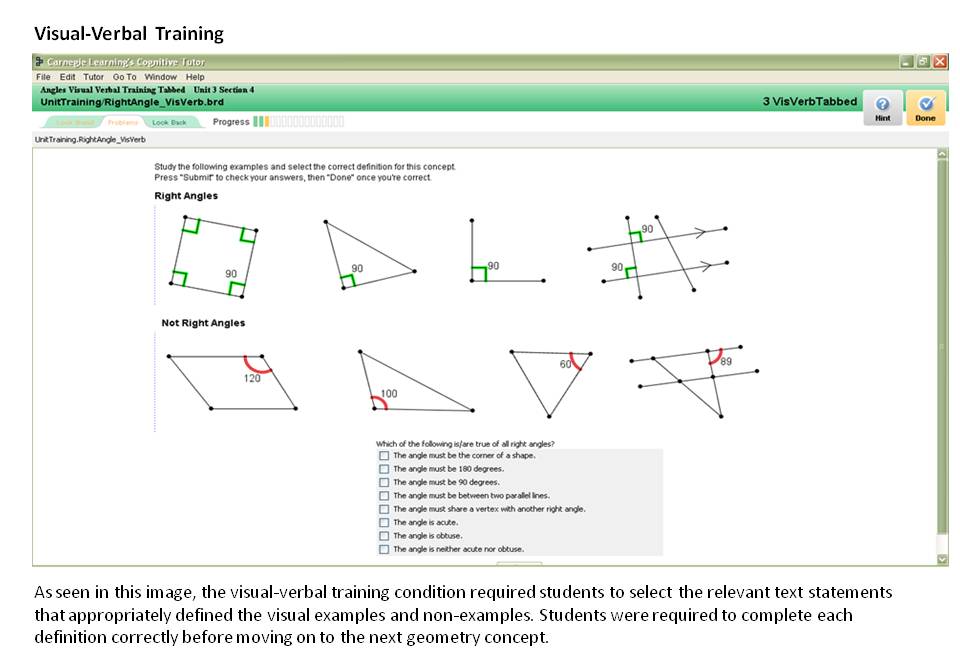

Study 2: How does coordination of visual and verbal information sources support visual feature understanding and application? This in vivo study extends our understanding of coordinative learning by addressing whether visual-verbal coordination maximizes robust learning when coordination is tied to student errors during problem solving. This study was conducted at CWCTC, beginning in late January 2008. The study curriculum was the Angles units of the Geometry Cognitive Tutor. In a 3 condition study, we varied the coordinative learning activities following student errors in the tutor.

Study 2: Independent Variables

No Highlighting: Following an error, no highlighting in the visual diagram is provided to students.

Tutor Highlighting: Following an error, the tutor highlighted the features of the problem diagram that are relevant to the selected geometry principle.

Student Highlighting: Following an error, the student is required to highlight the relevant visual information associated with geometry principles (namely, the features in the diagram to which the selected rule applies).

Results

Study 1

Although we hypothesized that coordinative support in linking verbal definitions of geometry concepts to visual examples would support the development of robust knowledge, visual only training was found to be as effective as coordinated visual-verbal training in this study. During early use of the tutor (as seen in the Concept Quiz 1 and Unit 1 Problem Solving results), the pattern of results showed an advantage for students trained in the visual-only condition. However, by posttest (see Overall True/False in the graph), students performed similarly on knowledge assessments.

Study 2

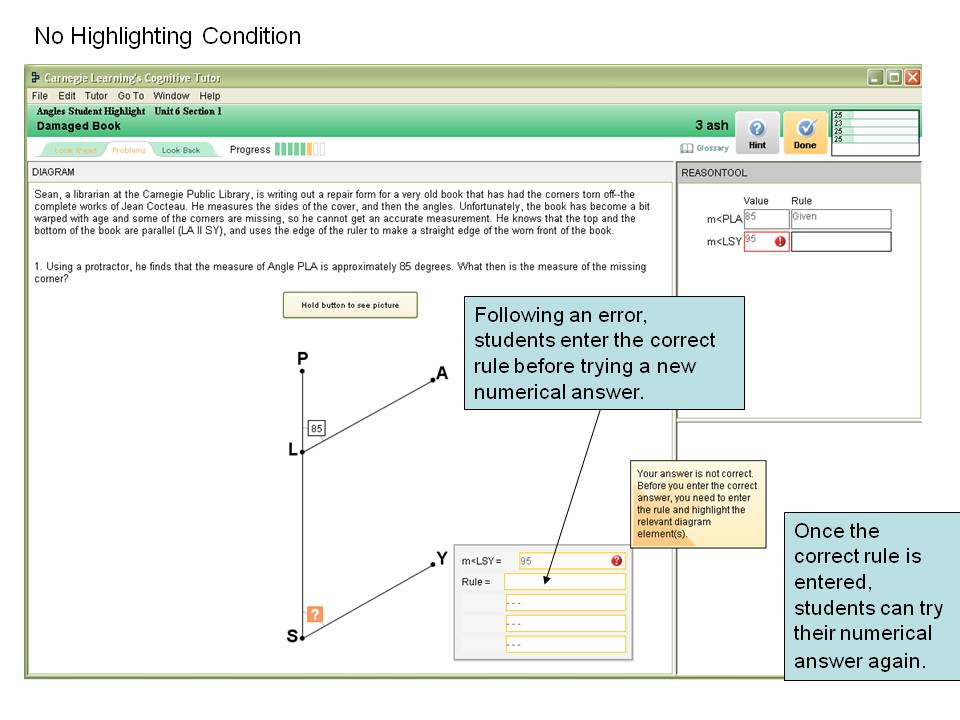

We hypothesized that active coordination -- where students highlight relevant diagram elements following problem-solving errors -- would best support robust learning. Although tutor highlighting was hypothesized to be better than the no highlighting (control) condition, we expected that visual-verbal coordination would be best supported by student interaction with diagrams.

Overall, student progress was slower than anticipated by the experimenters or the classroom teacher. Of the 83 students working in the intelligent tutor, 31 students (11 Control, 10 Visual Highlighting, 10 Visual Cueing) reached the last instructional unit (unit 3) during the experiment. For these students, results show that benefits of visual self-explanation for problem solving change over the course of tutoring practice (see the figure below).

In the first instructional unit, students provided with visual cueing by the tutor are most accurate in their problem solving answers (M = .89, SD = .05) compared to students in the control condition (M = .83, SD = .06) or the visual-explanation condition (M = .85, SD = .05). Results demonstrated an overall effect of condition (F (2, 27) = 4.01, p = .03); post-hoc Bonferroni comparisons demonstrated that visual cueing significantly outperformed the control condition (p = .03) but not the visual self-explanation condition (p = .15), which fell between the two other groups. In contrast, by unit 3, students who visually self-explained the geometry principles (M = .86, SD = .08) were most accurate in their problem-solving answers, followed by the visual cueing condition (M = .83, SD = .11), and then the control condition (M = .73, p = .10). Results again demonstrated an overall effect of condition (F(2, 27) = 4.84, p = .016); post-hoc Bonferroni comparisons showed that the control condition was outperfomed by the visual self-explanations (p = .03) and the visual cueing (p = .05) conditions.

We analyzed overall posttest and delayed posttest results for students who had also taken the pretest. Posttest results demonstrated an overall improvement from pre- to posttest (F(1, 65) = 9.68, p = .03), but no significant condition differences (F<1). At delayed posttest, result suggested a test time (pretest vs. delayed posttest) by condition interaction (F(2. 37) = 2.87, p = .07). At delayed posttest (see Figure 2), students in the visual self-explanation condition outperformed students from the visual cueing condition and the control (interactive diagram) condition.

Explanation

From a Coordinative Learning Cluster perspective, coordination between visual and verbal information supports foundational skill building, because attending to both representations simultaneously associates features from both with the learned knowledge components. This association increases feature validity and promotes robust learning.

Further Information

Connections

Annotated Bibliography

- Butcher, K. R., & Aleven, V. (2007). Integrating visual and verbal knowledge during classroom learning with computer tutors. In D. S. McNamara & J. G. Trafton (Eds.), Proceedings of the 29th Annual Cognitive Science Society (pp. 137-142). Austin, TX: Cognitive Science Society.

- Butcher, K. R., & Aleven, V. A. (in press 2009). Visual self-explanation during intelligent tutoring? More than attentional focus? European Association for Research on Learning and Instruction, 13th Biennial Conference. August 25-29, 2009: Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

References

Future Plans

- August 2009: Symposium presentation at EARLI 2009

- July - September 2009: Prepare article and submit to journal