Difference between revisions of "Fostering fluency in second language learning"

m |

m (→PSLC-related publications and presentations) |

||

| (144 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

|- | |- | ||

! Project title | ! Project title | ||

| − | | Fostering fluency in second language learning: | + | | Fostering fluency in second language learning: Testing two types of instruction |

| − | Testing two types of instruction | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | ! | + | ! Principal Investigator |

| − | | | + | | Dr. N. de Jong (faculty, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam) |

|- | |- | ||

| − | ! Co- | + | ! Co-PIs |

| − | | Perfetti (faculty) | + | | Dr. L.K. Halderman (post-doc, University of Pittsburgh) |

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | Dr. C.A. Perfetti (faculty, University of Pittsburgh) | ||

|- | |- | ||

! Others with > 160 hours | ! Others with > 160 hours | ||

| − | | Claire Siskin | + | | Claire Siskin, Jessica Hogan, John laPlante, Mary Lou Vercellotti |

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! Study start and end dates | ||

| + | | Study 1: September - November 2006 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | Study 2: January - March 2007 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | Study 3: January - March 2007 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | Study 4: January - March 2008 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | Study 5: September - November 2008 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | Study 6: October - December 2009 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | Study 7: Februari - March 2010 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | Study 8: October - December 2010 | ||

|- | |- | ||

! Learnlab | ! Learnlab | ||

| − | | ESL | + | | [[ESL]], Speaking courses (levels 3, 4, 5) |

|- | |- | ||

! Number of participants | ! Number of participants | ||

| − | | | + | | 350 |

|- | |- | ||

! Total Participant Hours | ! Total Participant Hours | ||

| − | | | + | | 825 hours |

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! Datashop | ||

| + | | Audio files and transcripts of Studies 1 through 4 are available | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | ! | + | ! Current status |

| − | | | + | | (July 2011) Paper about study 1 is published; paper about study 4 is under review; papers about studies 2 and 6 are in preparation. Many results have been presented at conferences. |

| + | Transcription and coding of studies 7 and 8 is in progress. Analysis of studies 5 and 6 is in progress. | ||

|} | |} | ||

== Abstract== | == Abstract== | ||

| − | Many studies have investigated the effect of exposure to language on [[fluency]]. It has been established, for instance, that [[fluency]] increases after a period of immersion or study abroad (Freed et al., 2004; Segalowitz & Freed, 2004). | + | [[Image:Vercellotti-DeJong GURT09 English L2 Verb Complements.gif|thumb|Verb Complement Errors (GURT09)]] [[Image:Fluency_DeJong-et-al_AB-visit_Sp09.gif|thumb|Speech Repetition and Fluency Development (Advisory Board Spring 2009)]] [[Image:Fluency_DeJong-et-al_iSLC_Sp09.gif|thumb|Elicited Imitation (iSLC Spring 2009)]] [[Image:Fluency_DeJong-et-al_IA_Sp09.gif|thumb|4/3/2 procedure (Industrial Affiliates Spring 2009)]] |

| + | |||

| + | Many studies have investigated the effect of exposure to language on [[fluency]]. It has been established, for instance, that [[fluency]] increases after a period of immersion or study abroad (Freed et al., 2004; Segalowitz & Freed, 2004). However, few types of instruction have been designed to increase oral [[fluency]], and even fewer have been tested. | ||

| + | |||

| + | One such type of instruction is Nation’s 4/3/2 procedure, in which learners prepare a four-minute talk and repeat it twice to different partners, first in three minutes, then in two minutes (Nation, 1989). He found that the number of hesitations decreased in the retellings, and that sentences were more complex. We may characterize such an outcome as resulting from the [[fluency pressure]] exerted by the 4/3/2 procedure. It was not investigated, however, whether the effect transferred to new speeches, which is what we showed in Study 1. Another task that may increase [[fluency]] is shadowing, in which student talk along with a recording of a short speech by a native speaker. Shadowing may also increase the feature [[strength]] of formulaic sequences, resulting in faster access to them in subsequent production tasks. | ||

| + | |||

| + | This project is transformative in the sense that it moves research on fluency away from single- or multiple-case studies, using technology to collect and analyze larger amounts of oral production data (30 to 40 students per study), and to generate multiple measures of fluency, accuracy, and complexity. For example, not only articulation rate is measured, but also pause length, length of fluent run, and phonation/time ratio. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Study 1 investigated what characteristics of [[fluency]] are affected by the 4/3/2 procedure. Measures included the number of syllables per second (speech rate); mean length of fluent runs between pauses; phonation/time ratio; number of interphrasal and intraphrasal pauses; morphosyntactic accuracy; and number of embedded clauses (syntactic complexity). The posttest tested transfer to a different topic. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In Study 2 we investigated whether [[fluency]] is further enhanced by a pretraining of formulaic sequences, like ''the point is that'', ''what I’m saying is that'', and ''and so on''). Fast and effortless access to these sequences frees up [[cognitive headroom]] which can then be used to construct sentences. This results in fewer and shorter pauses, and/or greater lexical and structural complexity. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Study 3 investigated whether shadowing leads to increased use of formulaic sequences ([[chunking]]) and native-like pauses in subsequent production tasks. | ||

| − | + | In studies 4 and 5 are investigating in further detail how the characteristics of the 4/3/2 task lead to fluency development. In Study 4a, we investigated how time pressure affects the benefits of repetition in terms of fluency, accuracy and complexity. We examined recordings both from the 4/3/2 task itself, and from long-term retention tests. In addition, we investigated the role of specific knowledge components in fluency development. | |

| − | In Study | + | In Study 4b we tracked how the control and retrieval of specific vocabulary items and morphosyntactic structures develop as a result of the 4/3/2 training. Next, in Study 5, we examined whether priming these same items leads to greater accuracy and fluency during training and later. Data collection for Studies 4a, 4b and 5 took place in the Spring and Fall 2008 semesters, in the English as a Second Language (ESL) learnlab (level 4, higher intermediate). Data analysis is currently in progress. |

| + | |||

| + | (Posters presented in Spring 2009 are shown on the right. Click on the thumb images to see the larger images.) | ||

== Glossary == | == Glossary == | ||

| − | ; 4/3/2 procedure: A teaching method in which students talk about a topic for four minutes. Then they repeat their speech in three minutes, and again in | + | ; 4/3/2 procedure: A teaching method in which students talk about a topic for four minutes. Then they repeat their speech in three minutes, and again in two minutes. |

; Shadowing: Repeating speech while it is being spoken. | ; Shadowing: Repeating speech while it is being spoken. | ||

| − | ; Formulaic sequence: A sequence, | + | ; Formulaic sequence: A sequence, continuous or discontinuous, of words or other elements, which is, or appears to be, prefabricated (see Wray, 2002, p. 9), e.g., ''The point is that'', ''What I'm trying to say is that'', and ''Take something like''. |

; Articulation rate: Number of syllables per second | ; Articulation rate: Number of syllables per second | ||

; Phonation/time ratio: The percentage of time spent speaking as a percentage proportion to the time taken to produce the speech sample | ; Phonation/time ratio: The percentage of time spent speaking as a percentage proportion to the time taken to produce the speech sample | ||

| − | ; Morphosyntactic accuracy: | + | ; Morphosyntactic accuracy: In this study we will investigate subject-verb agreement, tense errors, definite/indefinite articles |

| − | ; Syntactic complexity: | + | ; Syntactic complexity: In this study we will investigate the number of embedded finite and non-finite clauses |

== Research questions == | == Research questions == | ||

| − | + | === Study 1 === | |

| − | * Study 2 | + | * a. What characteristics of [[fluency]] are affected by repetition of a short speech under increasing time pressure (the 4/3/2 procedure)? |

| − | + | * b. Does knowledge [[refinement]] take place during the 4/3/2 training, in terms of morphosyntactic accuracy and syntactic complexity? | |

| − | + | === Study 2 === | |

| − | + | * a. Does pretraining of formulaic sequences lead to an increase in their use in the subsequent 4/3/2 procedure and posttest? If so, does this increase overall [[fluency]]? | |

| + | * b. Does proficiency level affect [[fluency]] development during the 4/3/2 procedure? | ||

| + | === Study 3 === | ||

| + | * a. What characteristics of [[fluency]] are affected by shadowing a text with formulaic sequences and a pausing pattern characteristic of spontaneous speech? | ||

| + | * b. Does shadowing texts with formulaic sequences lead to an increase in their use in the posttest? If so, does this increase overall [[fluency]]? | ||

| + | |||

| + | For studies 2 and 3, questionnaire data were collected about the students' contact with the second language (English) and their first language, in terms of ''types of contact'' (e.g., listening to the radio, talking to friends, talking to strangers) and ''amount of contact'' (number of days per week, number of hours per day). We will explore whether these [[individual differences]] affect pretest performance and fluency development. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Study 4 === | ||

| + | * a. How do time pressure and repetition affect fluency, accuracy and complexity in the 4/3/2 task? | ||

| + | * b. Which knowledge components contribute to fluency development in the 4/3/2 task? | ||

| + | === Study 5 === | ||

| + | * Does priming lead to an immediate and a long-term increase in fluency, accuracy and complexity? | ||

| + | === Study 6 - pilot for studies 7 and 8 === | ||

| + | * What prompts will be most appropriate for studies 7 and 8 (to test the effect of time pressure on fluency, accuracy, and complexity)? | ||

| + | === Study 7 === | ||

| + | * What is the effect of increasing time pressure on fluency, accuracy, and complexity in immediately repeated speeches? | ||

| + | === Study 8 === | ||

| + | * What is the long-term effect of increasing time pressure on fluency, accuracy, and complexity? | ||

== Background and significance == | == Background and significance == | ||

| Line 59: | Line 121: | ||

The first activity that is tested is the 4/3/2 procedure as proposed by Nation (1989). He investigated the development of [[fluency]] during this task, but used a limited number of measures and did not test the long-term effect: he only analyzed [[fluency]] during the task itself, not during the following weeks. This project will test the long-term effect and will include more measures, such as length and location of pauses. An attempt will be made to link these measures to cognitive mechanisms. | The first activity that is tested is the 4/3/2 procedure as proposed by Nation (1989). He investigated the development of [[fluency]] during this task, but used a limited number of measures and did not test the long-term effect: he only analyzed [[fluency]] during the task itself, not during the following weeks. This project will test the long-term effect and will include more measures, such as length and location of pauses. An attempt will be made to link these measures to cognitive mechanisms. | ||

| − | + | A general effect of the 4/3/2 task on fluency development was found in Study 1. The effect was investigated in more detail in Study 4a, focusing on the two main characteristics of the task: repetition and increasing time pressure. | |

| + | |||

| + | The contribution of knowledge components is tested in Studies 2, 4b and 5. In Study 2, students received a pretraining of a set of formulaic sequences before the first 4/3/2 fluency training session. In Study 5 students received a pretraining at the start of each 4/3/2 fluency training session. The knowledge components in this pretraining was selected based on the results of Study 4b, which investigated the role of vocabulary breadth, vocabulary depth and grammatical knowledge in oral fluency. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Study 3 investigated whether shadowing affected fluency development. In addition, it was tested whether the presence of formulaic sequences in the model speeches increased use of those sequences in later speaking tasks, and whether such an increase affected [[fluency]] measures. | ||

== Dependent variables == | == Dependent variables == | ||

| + | === Fluency, accuracy, and complexity === | ||

* Temporal measures of [[fluency]]: | * Temporal measures of [[fluency]]: | ||

** Articulation rate: number of syllables per second | ** Articulation rate: number of syllables per second | ||

| Line 69: | Line 136: | ||

***phonation/time ratio | ***phonation/time ratio | ||

***number of interphrasal and intraphrasal pauses | ***number of interphrasal and intraphrasal pauses | ||

| − | ** Formulaic sequences: number of appropriate formulaic sequences repeated from | + | ** Formulaic sequences: number of appropriate formulaic sequences repeated from training |

| − | * Accuracy: morphosyntactic accuracy (subject-verb agreement, tense errors, | + | * Accuracy: morphosyntactic accuracy (target-like use of several structures, including subject-verb agreement, tense errors, and definite/indefinite articles; see Mizera, 2006: 71) |

| − | * Complexity: number of embedded finite and non-finite clauses (cf. Nation, 1989) | + | * Complexity: number of embedded finite and non-finite clauses (cf. Nation, 1989); lexical variety as measured by the Mean Segmental Type-Token Ratio (Towell, Hawkins & Bazergui, 1996) |

| − | * ''Near transfer, immediate, [[normal post-test]]'': | + | === Transfer === |

| + | * ''Near transfer, immediate and delayed, [[normal post-test]]'': After completing the last training session, students performed a similar task (spontaneous speech about a given topic), to test whether any gains in [[fluency]] during the training task were maintained in a new instance of the same task. This test was given one week and four weeks after the last training session, each time with a different topic. These recordings were made as part of the Recorded Speaking Activities (RSAs) from the project "[[The self-correction of speech errors (McCormick, O’Neill & Siskin)]]". | ||

| + | * ''Far transfer, delayed'': The delayed posttests in Study 4 will include measures of vocabulary breadth, vocabulary depth and grammatical knowledge. | ||

== Independent variables == | == Independent variables == | ||

| + | (For screenshots exemplifying some of the independent variables, see Screenshots below.) | ||

* Studies 1-3: Pretest vs. immediate posttest vs. [[long-term retention]] posttest | * Studies 1-3: Pretest vs. immediate posttest vs. [[long-term retention]] posttest | ||

* Study 1: Repetition vs. No Repetition | * Study 1: Repetition vs. No Repetition | ||

| Line 81: | Line 151: | ||

* Study 2: | * Study 2: | ||

** a. Pretraining vs. no pretraining of formulaic sequences | ** a. Pretraining vs. no pretraining of formulaic sequences | ||

| − | ::In the Formulaic Sequences condition, students receive a short training of a number of formulaic sequences before they start the [[fluency]] training (4/3/2 task). In the No Formulaic Sequences condition, students do not receive this pretraining, and only do the 4/3/2 task. | + | :: In the Formulaic Sequences condition, students receive a short training of a number of formulaic sequences before they start the [[fluency]] training (4/3/2 task). In the No Formulaic Sequences condition, students do not receive this pretraining, and only do the 4/3/2 task. |

:* b. Low intermediate vs. high intermediate proficiency level | :* b. Low intermediate vs. high intermediate proficiency level | ||

:: Low intermediate students are enrolled in ELI Speaking courses at level 3, high intermediate at level 4. | :: Low intermediate students are enrolled in ELI Speaking courses at level 3, high intermediate at level 4. | ||

* Study 3: Shadowing text with formulaic sequences vs. without formulaic sequences | * Study 3: Shadowing text with formulaic sequences vs. without formulaic sequences | ||

| − | ::In the Formulaic Sequences condition, students shadow texts that contain formulaic sequences. In the No Formulaic Sequences condition, students shadow the same texts, from which the formulaic sequences that are being studied have been removed. | + | :: In the Formulaic Sequences condition, students shadow texts that contain formulaic sequences. In the No Formulaic Sequences condition, students shadow the same texts, from which the formulaic sequences that are being studied have been removed. |

| + | * Study 4: | ||

| + | ** a. Repetition vs. No Repetition | ||

| + | :: The 4/3/2 task will include either 1 topic (repeated) or 3 topics (not repeated) | ||

| + | ** b. Increasing Time Pressure vs. No Increasing Time Pressure | ||

| + | :: The 4/3/2 task will include recordings of either 4, 3 and 2 minutes, or 3, 3, and 3 minutes | ||

| + | * Study 5: Pretraining vs. no pretraining of vocabulary and grammar knowledge components | ||

| + | :: In the Pretraining condition, students perform short tasks before the 4/3/2 training sessions to prime their vocabulary and grammar knowledge. Students in the No Pretraining condition do not receive this pretraining. | ||

== Hypotheses == | == Hypotheses == | ||

| − | + | === Study 1 === | |

| − | + | * It is hypothesized that repetition of a short speech (independent variable) under increasing time pressure ([[fluency pressure]]) increases articulation rate and sentence complexity (dependent variables), and decreases the number and length of pauses (dependent variables). The reason is that repetition will--temporarily--increase the [[availability]] of vocabulary and sentence structures (leading to increase speech rate, short and fewer pauses), leaving more [[cognitive headroom]] for other processes (higher accuracy and syntactic complexity). | |

| − | * | + | |

| − | + | === Study 2 === | |

| + | * It is hypothesized that the presence of a pretraining of formulaic sequences (independent variable) leads to an increase in their use in subsequent spontaneous speech (dependent variable). Effortless use of these sequences will free up [[cognitive headroom]] for sentence structure planning, which may lead to overall more fluent performance, in terms of speed and pausing patterns (dependent variables). Thus, the training of formulaic sequences may accelerate [[accelerated future learning|future learning]]. | ||

| + | * Students at different proficiency levels may benefit in different ways from the 4/3/2 training. At lower proficiency levels, repetition may facilitate the use of particular words and grammar, leading to more instances of correct usage of vocabulary, morphosyntax and syntax. At higher proficiency levels, on the other hand, repetition may lead to a greater number of reformulations resulting in higher complexity. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Study 3 === | ||

| + | * It is hypothesized that shadowing a speech that contains formulaic sequences (independent variable) leads to an increase in their use in subsequent spontaneous speech (dependent variable). Since effortless use of these sequences will free up [[cognitive headroom|headroom]] for sentence structure planning, performance may become more fluent overall, in terms of speed and pausing patterns (dependent variables). Thus, shadowing may accelerate [[accelerated future learning|future learning]]. In addition, shadowing a text with target-language pausing patterns is expected to lead to a more native-like pausing pattern in subsequent spontaneous speech, mainly in terms of position (dependent variables: interphrasal and intraphrasal pauses). | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Study 4 === | ||

| + | * Study 4 a: We hypothesize that time pressure in combination with speech repetition encourages a strategy of retrieval (shorter pauses, high lexical overlap between two subsequent recordings), while repetition without time pressure encourages computation, leading to higher accuracy and complexity with lower fluency. We expect that the strategy of computation may result in higher fluency in the longer term, because it leads to more [[refinement]] and [[strength|strengthening]] of knowledge components, thus reducing hesitations and [[automaticity|accelerating retrieval]] in future speeches (cf. the [[assistance|assistance dilemma]]). | ||

| + | * Study 4b: We hypothesize that students with a broader vocabulary—-since they have more words to choose from—-will be able to find an appropriate word more often and more quickly, and therefore speak more fluently (shorter and fewer pauses, fewer hesitations). This is a measure of individual differences, and of general vocabulary knowledge. Greater vocabulary depth will also increase fluency, because students have more control over vocabulary items. In addition, it is predicted that retrieval speed for words used in the fluency training will show a increase in retrieval speed compared to items that were used in the fluency training. Finally, we expect to find a positive correlation between fluency in speech production and the accuracy scores on a test of morphosyntactic knowledge. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Study 5 === | ||

| + | * We hypothesize that the pretraining will lead to more fluent speech production, as well as more accurate and more complex output. We expect that this effect will be retained on the posttest and delayed posttest. This would be an example of [[accelerated future learning]] through [[feature focusing]]. | ||

| + | === Study 6 === | ||

| + | * This is an exploratory pilot study to test instructions and prompts for a new study, which will focus on the effect of time pressure on fluency and fluency developement (cf. Study 4a). The new speaking prompts will be picture stories, in order to create "pushed output" and to increase comparability of performance across students. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Study 7 === | ||

| + | This is a pilot study for Study 8, to examine the effect of time pressure on repeated and non-repeated story retellings. If a difference between the two groups is found, Study 8 will investigate the longer-term effects of time pressure. | ||

| + | * We hypothesize that time pressure in combination with speech repetition encourages a strategy of retrieval (shorter pauses, high lexical overlap between two subsequent recordings), while repetition without time pressure encourages computation, leading to higher accuracy and complexity with lower fluency. We expect that the strategy of computation may result in lower fluency in the short term (but higher fluency in the longer-term; see Study 8). | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Study 8 === | ||

| + | This is a partial replication of Study 4, with tighter control over variables such as the content of the speeches, and with larger group sizes. | ||

| + | * We hypothesize that time pressure in combination with speech repetition encourages a strategy of retrieval (shorter pauses, high lexical overlap between two subsequent recordings), while repetition without time pressure encourages computation, leading to higher accuracy and complexity with lower fluency. We expect that the strategy of computation may result in higher fluency in the longer term, because it leads to more [[refinement]] and [[strength|strengthening]] of knowledge components, thus reducing hesitations and [[automaticity|accelerating retrieval]] in future speeches (cf. the [[assistance|assistance dilemma]]). | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Robust learning === | ||

* ''Near transfer, immediate'': In all studies, a posttest is administered about a week after the last training session. This will be a similar task—a 2-minute monologue—with new content—a new topic. | * ''Near transfer, immediate'': In all studies, a posttest is administered about a week after the last training session. This will be a similar task—a 2-minute monologue—with new content—a new topic. | ||

* ''Near transfer, retention'': In Studies 1 and 2, another posttest is administered two to three weeks after the immediate posttest (three to four weeks after the last training session). Again, this will be a similar task—a 2-minute monologue—with new content—a new topic. | * ''Near transfer, retention'': In Studies 1 and 2, another posttest is administered two to three weeks after the immediate posttest (three to four weeks after the last training session). Again, this will be a similar task—a 2-minute monologue—with new content—a new topic. | ||

| − | * ''[[accelerated future learning|Acceleration of future learning]]'': In Study | + | * ''[[accelerated future learning|Acceleration of future learning]]'': In Study 5, the students in the experimental condition first receive a pretraining of a number of formulaic sequences. It will be tested whether their [[fluency]], accuracy and syntactic complexity increases more during subsequent training, than of students who do not receive this pre-training. |

== Findings == | == Findings == | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | === Study 1: Repetition, proceduralization and L2 fluency === | |

| + | [[Image:FluencyStudy1_SPR-Session1.JPG|thumb]] [[Image:FluencyStudy1_SPR-Session2.JPG|thumb]] [[Image:FluencyStudy1_SPR-Session3.JPG|thumb]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''Fluency during the 4/3/2 task'' | ||

| + | |||

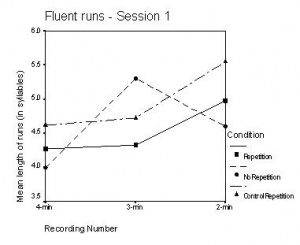

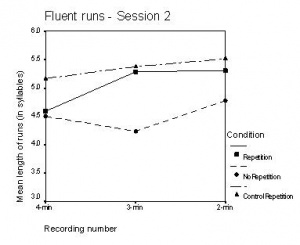

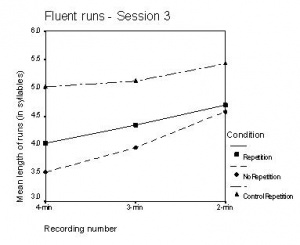

| + | During each training session, the mean length of fluent runs increased mostly for the two conditions in which speeches were repeated (Repetition and Control/Repetition). In addition, for all three groups, pauses, on average, became shorter, and phonation/time ratio increased (i.e., students were able to fill more time with speech). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Figures 1, 2 and 3 show the mean length of fluent runs for each recording in each of the sessions. It is clear that in sessions 1 and 2 the two conditions in which speeches were repeated pattern more closely together than the condition in which speeches were not repeated. The improvement in performance of the two repetition conditions seems more stable, whereas the performance of the No Repetition condition seems to be influenced by the topic of a particular speech. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ''Transfer to new topics'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | On the immediate posttest, students in the Repetition condition are able to produce the same length of fluent runs with shorter pauses. Also, they fill relatively more time with speech (increased phonation/time ratio). It seems, therefore, that they speak more fluently than students in the No Repetition condition. However, on the delayed posttest, the No Repetition condition seems to have caught up with the Repetition condition, also having shorter pause lengths, with stable lengths of fluent runs. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Both groups reach a higher articulation rate, measured in syllables per minutes, on the delayed posttest. This may have been due to their continued Speaking classes in the English Language Institute, and may not have been related to this study. | ||

| + | |||

| + | It should be noted that the posttests were administered one and four weeks after the last session of the [[fluency]] training, and involved a new topic, which the students had not talked about during the 4/3/2 training. | ||

{|+ Preliminary results Study 1 | {|+ Preliminary results Study 1 | ||

| − | ! !! align="center" colspan=" | + | ! !! align="center" colspan="3" | No Repetition (n=9) !! !! colspan="3" | Repetition (n=10) !! !! colspan="3" | Control&Repetition (n=5) |

|- | |- | ||

| − | ! align="center" | !! Pretest !! | + | ! align="center" | !! Pretest !! Immediate !! Delayed !! !! Pretest !! Immediate !! Delayed !! !! Pre-pretest !! Pretest !! Immediate |

|- | |- | ||

| − | ! align="left" | Length of fluent runs (in syllables) | + | ! align="center" | !! !! Posttest !! Posttest !! !! !! Posttest !! Posttest2 !! !! !! !! Posttest |

| − | | align="center" | 4. | + | |- |

| + | ! align="left" | Length of fluent runs (in syllables) * | ||

| + | | align="center" | 4.42 || align="center" | 4.11 || align="center" | 4.27 || || align="center" | 4.42 || align="center" | 4.82 || align="center" | 4.69 || || align="center" | 4.58 || align="center" | 4.80 || align="center" | '''5.44''' | ||

|- | |- | ||

! align="left" | Pause length (in sec.) * | ! align="left" | Pause length (in sec.) * | ||

| − | | align="center" | 0. | + | | align="center" | 0.92 || align="center" | 1.08 || align="center" | 0.96 || || align="center" | 1.18 || align="center" | '''0.96''' || align="center" | 0.99 || || align="center" | 0.99 || align="center" | 0.97 || align="center" | 0.84 |

|- | |- | ||

! align="left" | Phonation/time ratio * | ! align="left" | Phonation/time ratio * | ||

| − | | align="center" | 0. | + | | align="center" | 0.59 || align="center" | 0.55 || align="center" | 0.57 || || align="center" | 0.54 || align="center" | '''0.60''' || align="center" | 0.59 || || align="center" | 0.57 || align="center" | 0.59 || align="center" | 0.62 |

|- | |- | ||

! align="left" | Syllables per minute | ! align="left" | Syllables per minute | ||

| − | | align="center" | | + | | align="center" | 194 || align="center" | 190 || align="center" | '''204''' || || align="center" | 196 || align="center" | 196 || align="center" | '''204''' || || align="center" | 209 || align="center" | 214 || align="center" | 232 |

|} | |} | ||

<nowiki>*</nowiki> Significant interaction Condition x Time | <nowiki>*</nowiki> Significant interaction Condition x Time | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ''Conclusion'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | The results of Study 1 suggest that knowledge becomes more easily accessible in subsequent speeches, since phonation/time ratio increases while pauses on average become shorter and the length of fluent runs is at least stable. In the two conditions in which speeches are repeated, the length of fluent runs increases, indicating an advantage over the no-repetition condition, in which this length is stable. It seems, therefore, that repeating a speech about a particular topic enables students to produce longer fluent runs. The overall advantage of these two conditions over the no-repetition condition parallels patterns in the pre- and posttest data. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Overall, it seems that the performance of the no-repetition condition was more variable across speeches. This may be due to an effect of topic, which may be more or less familiar, complex, or linguistically difficult (e.g., eliciting present vs. past tense). | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Study 2: Formulaic sequences === | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:FormSeq-per-speech for-wiki.jpg|thumb]] | ||

| + | |||

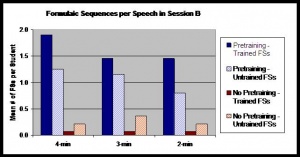

| + | A pretraining of ten formulaic sequences led to an increase in their use during the 4/3/2 procedure. However, students often used the sequences incorrectly, and some students used them more than others. There was very little transfer to other speaking tasks. | ||

| + | The use of formulaic sequences had a mixed effect on fluency, in that it led to longer fluent runs (higher fluency) but also longer pauses (lower fluency). The trained formulaic sequences were probably not stored as chunks, and retrieval was not automatized | ||

| + | Interestingly, after the pretraining students used more formulaic sequences that were not trained, as compared to the pretest and the students who had not received the pretraining. This is likely to be due to increased awareness of the existence and usefulness of formulaic sequences. These sequences with used with high accuracy. | ||

| + | Overall, it seems that the use of formulaic sequences was not effortless, and had a mixed effect on fluency. The form errors suggest that the students had learned formulaic sequences at the word level, and did not store and retrieve them as chunks (cf. Towell et al., 1996; Wray, 2002). | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | === Study 3: Shadowing and formulaic sequences === | ||

| + | Data transcribed and coded. Analyses in progress. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | === Study 4: The role of vocabulary and grammar in L2 fluency (PRELIMINARY FINDINGS) === | ||

| + | |||

| + | Several tests were used to assess students' linguistic knowledge (vocabulary, grammar): Immediate Picture Naming, Delayed Picture Naming, Vocabulary Knowledge Scale, and Elicited Imitation. Performance on these tests was mostly as predicted, e.g., in terms of pre/posttest effects and frequency effects, as shown by the following findings. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ''Breadth of productive vocabulary: Picture Naming accuracy'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Accuracy improved from pretest (74.2%) to posttest (85.7%), and was higher on the 1-1000 frequency band (85.7%) compared to the 2001-3000 frequency band (74.2%). There was a greater difference between the frequency bands in the Immediate naming condition compared to the Delayed naming condition. Therefore, naming lower-frequency words seems to be more difficult under time pressure (Immediate naming) than under no time pressure (Delayed naming). | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ''Retrieval speed of vocabulary: Picture Naming response time'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Delayed naming condition was significant faster (1.046 seconds) compared to the Immediate naming condition (1.794 seconds). Only in the Delayed condition did reaction times improve from pretest (1.303 seconds) to posttest (0.670 seconds). These findings suggest that changes occurred over the course of the semester for the Delayed condition only. This may be due to improvements in articulation rate rather than lexical retrieval since lexical retrieval is executed prior to the cue to name. If improvements in lexical retrieval had occurred, there should have been a reduction in reaction time at the posttest for the immediate condition since immediate naming includes lexical retrieval and articulation rate. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ''Vocabulary depth and productive use: Vocabulary Knowledge Scale'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Depth of knowledge for nouns was less affected by frequency than verbs. However, for high-frequency verbs, depth of knowledge was similar to that of nouns. These findings suggest that extra experience or enhanced instruction may be necessary for ESL students to acquire rich representations of low-frequency verbs. The scores for most categories (all nouns and high and mid frequency verbs) were on average around 4 ("I know this word. It means: ..."), which indicates that the students had good receptive depth of knowledge of these words, but were just short of productive knowledge. It seems therefore that these words were ready to be brought into productive use, but most were note in productive use yet, even the 2-3K words. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ''Productive grammatical ability: Elicited Imitation'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | "Grammatical ability" was tested with a range of forms and structures, morphosyntactic as well as syntactic, and less to more complex (earlier to later acquired). Elicited Imitation accuracy was marginally significantly higher on the posttest (50%) compared to the pretest (45%). | ||

| + | |||

| + | There were different patterns of performance across structures for the correct stimuli compared to the pattern observed for the incorrect stimuli. For correct stimuli, Relative Clauses and Plurals had among the best performance. However, when the stimuli were incorrect, subjects infrequently corrected them leading to poorer performance than expected given the high accuracy on the correct stimuli trials. Other structures like Regular Past Tense and Verb Complements were unaffected by the accuracy of the stimulus, showing no difference between the two conditions. The remaining structures (Embedded Questions, Indefinite Articles, Modals and Third Person –s) showed significantly better performance for the correct compared to the incorrect condition; however, performance on these structures relative to other structures was similar across accuracy conditions. On average students clearly had some knowledge of the grammatical items tested, because they were able to correctly repeat most of the correct stimuli. However, scores were fairly low, well below the 90% that is often used as a criterion for acquisition. Also, performance was strongly affected by ungrammatical stimuli, which shows that the students’ knowledge or processing of the grammatical items was variable. This poor performance was found both for grammatical forms and structures that are typically late acquired (e.g., third person –s, embedded questions) and relatively early acquired (e.g., noun plurals, regular past) | ||

| + | |||

| + | For relative clauses and plurals (and perhaps some other forms), grammatically correct and incorrect forms appear to be seen as two acceptable alternatives, as indicated by the large difference between grammatically correct and incorrect stimuli. For these items, the low scores for incorrect stimuli were almost complementary to high scores for correct stimuli: 70-30%, and 70-15%). | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ''Linguistic knowledge and oral fluency'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | The relationship between linguistic knowledge (vocabulary, grammar) and temporal measures of oral fluency was examined: | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | '''Pretest''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Students with greater grammatical ability and deeper vocabulary knowledge spoke with longer fluent runs and higher articulation rates. In addition, students with a greater breadth of vocabulary used longer pauses and filled less time with speech. This finding is surprising. It is possible that students with larger vocabularies tried to use more words and more infrequent words, which led them to speak with lower fluency. This deserves further investigation. Finally, students whose lexical retrieval was faster were able to produce more syllables per minute of speech. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Posttest''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Students with greater grammatical ability spoke with higher articulation rates. Students with a greater breadth of vocabulary knowledge used shorter pauses and filled more time with speech. This finding was expected, but opposite to the pretest. Here, it seems that students with larger vocabularies were able to find words more easily, leading to higher fluency. Finally, students whose lexical retrieval was faster were able to produce more syllables per minute of speech. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Overall, grammatical ability seems to lead to higher articulation rate. Vocabulary depth is related to longer fluent runs and higher articulation rates, whereas findings for vocabulary breadth are variable, leading to longer or shorter pauses and more or less time filled with speech. Faster lexical retrieval is associated with a higher number of syllabes per minute of speech. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ''Gains in linguistic knowledge and gains in oral fluency'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | To be analyzed | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | === Study 5: Priming vocabulary and grammar for fluent production === | ||

| + | Data transcribed. Coding in progress. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | === Study 6: Piloting picture story prompts (PRELIMINARY FINDINGS) === | ||

| + | |||

| + | Note: Detailed findings were presented at AAAL 2011 and will be reported in De Jong and Vercellotti (forthcoming). | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''Native speakers'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Native-speaker data were examined for seven stories: | ||

| + | Frog, Picnic, Race, Rude Driver, Shopper, Turtle, Tiger | ||

| + | |||

| + | (Frog and Turtle consisted of six pictures selected from wordless storybooks by Mayer, 1967, 1971) | ||

| + | |||

| + | (All other pictures were six-picture stories from Heaton, 1965) | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Evaluations by speakers''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Clarity of the pictures and story lines, and recognizability of the characters was rated well for all stories, but lower for Frog and Turtle. Students reported that most stories contained sufficient information to talk about, but Shopper consistently scored low on this point. Shopper scored low on enjoyment/interest, while Tiger scored high (despite the Tiger being killed). All other stories got medium scores on enjoyment/interest, with some variability. Only Tiger had consistently low ratings for the statement “The pictures showed things that might happen in my country”. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ''Non-native speakers'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Non-native speaker data for five picture stories were examined: | ||

| + | Frog, Race, Rude Driver, Turtle, Tiger (Picnic and Shopper were dropped) | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | '''Amount of speech elicited''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | The amount of speech elicited was roughly similar for all five stories. Most students were able to produce close to four minutes of speech. Only with Turtle, a number of students had trouble filling 180 seconds. | ||

| + | |||

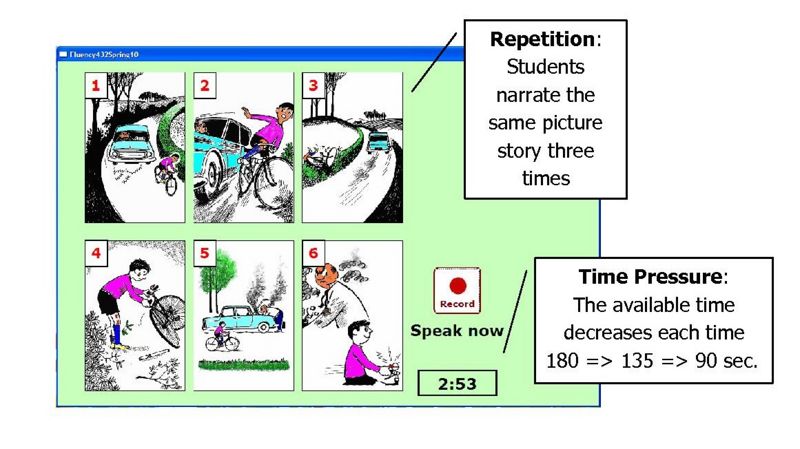

| + | In the main study, we will reduce the time available for speaking, from 4/3/2 minutes to 3/2.25/1.5 (180/135/90 sec.), so that there will be some time pressure for everyone. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | '''Evaluations by students''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Rude Driver, Race, and Tiger got the best ratings for clarity, interest, and plausibility. The ending of the Tiger story was evaluated negatively by some students. Frog and Turtle received lower ratings across the board. Frog and Turtle received lower ratings across the board; the image quality of these two stories was slightly lower, and the coherence of the panels may have been less because they were selected from a longer story. | ||

| + | |||

| + | All picture stories had a tight narrative structure. Most picture stories had a complex storyline (foreground and background information), except Tiger. The storyline for Frog can be considered slightly less complex. (Cf. the task features investigated by Foster & Tavakoli, 2009; Tavakoli & Foster, 2008.) | ||

== Explanation == | == Explanation == | ||

| − | This project | + | This project initially took part in the [[Refinement and Fluency]] cluster. The studies in this cluster concerned the design and organization of instructional activities to facilitate the acquisition, [[refinement]], and fluent control of critical [[knowledge components]]. The general hypothesis was that the structure of instructional activities affects learning. |

| − | This project addresses the core issues of task analysis, [[fluency]] from basics, [[in vivo experiment|in vivo]] evaluation, and scheduling of practice. The 4/3/2 task has been analysed into its components. In Study 1, the effect of the component of repetition | + | |

| + | This project addresses the core issues of task analysis, [[fluency]] from basics, [[in vivo experiment|in vivo]] evaluation, and scheduling of practice. The 4/3/2 task has been analysed into its components. In Study 1, the effect of the component of repetition was investigated. Practice with the basic skills of using vocabulary and grammar was expected to increase [[fluency]]. This would be the case in the Repetition condition, where students had the opportunity to re-use the words, formulaic sequences and grammar in subsequent recordings. In Study 2, students were encouraged to use formulaic sequences that had been taught prior to the fluency training sessions. In Study 3 it was investigated whether shadowing promoted the use of formulaic sequences in spontaneous speech. All three studies took place in an [[in vivo experiment|in vivo]] setting. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The project is currently participating in the [[Cognitive Factors]] thrust. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Further information == | ||

| + | |||

| + | For a summer intern project in June and July 2007, Kara Schultz did a multiple case study of six students from Study 1. The project was a first step towards more in-depth analyses of the data of all three studies in the ESL fluency project, addressing the following research questions: | ||

| + | * Does the absence of the need to generate new semantic content in the two retellings during the 4/3/2 task free up headroom, resulting in changes in fluency, morphosyntactic accuracy, and complexity? | ||

| + | * If so, what types of changes occur, and what are the causes for these changes? | ||

| + | * Is there long-term retention of the changes (one week)? | ||

| + | |||

| + | In September 2007 the PSLC executive committee approved our new project plan, in which we proposed follow-up studies that investigate the effect of time pressure and the role of specific knowledge components (vocabulary, grammar) in oral fluency. These studies will be run in the Spring and Fall semesters of 2008. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Descendants == | ||

| + | [[Fluency Summer Intern Project | Fluency Summer Intern Project 2007]] -- Kara Schultz | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Fluency Summer Intern Project 2008]] -- Megan Ross | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Fluency Summer Intern Project 2009]] -- Maya Randolph | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Fluency Summer Intern Project 2010]] -- Mariah Warren | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Fluency Summer Intern Project 2011]] -- Anthony Brohan | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Explicit and implicit knowledge of infinitival and gerundival verb complements in L2 speech]] | ||

== Annotated bibliography == | == Annotated bibliography == | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | - | + | Nation, I.S.P. (1989). Improving speaking fluency. ''System'', ''17'', 377-384. |

| + | * Studied the 4/3/2 task. Did not distinguish between effect of speech repetition and time pressure. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Foster, P., & Tavakoli, P. (2009). Native speakers and task performance: Comparing effects on complexity, fluency, and lexical diversity. Language Learning, 59(4), 866-896. | ||

| + | * Studied the effect of narrative structure and storyline complexity on fluency, accuracy, complexity, and lexical diversity in native speakers of English. See also Tavakoli and Foster (2008) for non-native-speaker data. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Freed, B. F., Dewey, D. P., Segalowitz, N., & Halter, R. (2004). The Language Contact Profile. ''Studes in Second Language Acquisition'', ''26'', 349-356. | ||

| + | * Developed a questionnaire about out-of-class language contact. Used in Study 2 and 3. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Freed, B. F., Segalowitz, N., & Dewey, D. P. (2004). Context of learning and second language fluency in French: Comparing regular classroom, study abroad, and intensive domestic immersion programs. ''Studies in Second Language Acquisition'', ''26'', 275-301. | ||

| + | * Used the Language Contact Profile questionnaire. Studied fluency development as a result of study abroad and immersion. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Mizera, G. J. (2006). ''Working memory and L2 oral fluency''. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh. | ||

| + | * Includes an investigation of native speaker ratings of oral fluency. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Segalowitz, N., & Freed, B. F. (2004). Context, contact, and cognition in oral fluency acquisition. ''Studies in Second Language Acquisition'', ''26'', 173-199. | ||

| + | * Studied fluency development as a result of study abroad. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Towell, R., Hawkins, R., & Bazergui, N. (1996). The development of fluency in advanced learners of French. ''Applied Linguistics'', ''17'', 84-119. | ||

| + | * Argued that proceduralization of linguistic knowledge shows up in second language speech as longer fluent runs with stable or improving pause length and phonation/time ratio. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Tavakoli, P., & Foster, P. (2008). Task Design and Second Language Performance: The Effect of Narrative Type on Learner Output. Language Learning, 58(2), 439-473. | ||

| + | * Studied the effect of narrative structure and storyline complexity on fluency, accuracy, complexity, and lexical diversity in non-native speakers of English. See also Foster and Tavakoli (2009) for native-speaker data. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == PSLC-related publications and presentations == | ||

| + | <nowiki>*</nowiki> Images available at top of page | ||

| + | |||

| + | De Jong, N. (to appear). Oefenen met vloeiend spreken: Wat, hoe en waarom? [Practicing speaking fluently: What, how, and why?] ''Vakwerk''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | De Jong, N. (2012). Short and longer term effects of time pressure on fluency in second language learners. ''Paper presented at the Workshop Fluent Speech'', November, 2012, Utrecht. | ||

| + | |||

| + | De Jong, N. (2012). Technieken voor het oefenen van vloeiend spreken. [Techniques for practicing speaking fluently] ''Workshop given at the LES Conference'', November, 2012, Amsterdam. | ||

| + | |||

| + | De Jong, N. & Seman, J-M. (2012). Effects of immediate task repetition, prompt type, and time pressure on repeated retrieval of vocabulary. ''Paper presented at the Second Language Research Forum'', October, 2012, Pittsburgh, PA. | ||

| + | |||

| + | De Jong, N. (2012). Oefenen met vloeiend spreken: Wat, hoe en waarom? [Practicing speaking fluently: What, how, and why?] ''Paper presented at the BVNT2 Conference'', June 2012, Hoeven. | ||

| + | |||

| + | De Jong, N. (2012). Does time pressure help or hinder oral fluency? In: N. de Jong, K. Juffermans, M. Keijzer, & L. Rasier (Eds.), ''Papers of the Anéla 2012 Applied Linguistics Conference'' (pp. 43-52). Delft: Eburon. | ||

| + | |||

| + | De Jong, N. (2012). Does time pressure help or hinder oral fluency? ''Paper presented at the Anéla Applied Linguistics Conference'', May 2012, Lunteren. | ||

| + | |||

| + | De Jong, N. & Poelmans, P. (2011). Accuracy and complexity in second language speech: Do specific measures make the difference? ''Paper presented at the EuroSLA conference'', Stockholm, September 2011. | ||

| + | |||

| + | De Jong, N. & Vercellotti, M.L. (2011). Norming picture story prompts for second language production research: Fluency, linguistic items, and speakers’ perception. ''Paper presented at the American Association for Applied Linguistics conference.'' Chicago, IL, March 2011. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Warren, M. (2011). The role of repeated grammatical structures in second language fluency. ''Paper presented at McGill's Canadian Conference for Linguistics Undergraduates.'' Montreal, QC, March 2011. | ||

| + | |||

| + | De Jong, N. & Halderman, L.K. (in preparation). The role of vocabulary and grammar knowledge in second language oral fluency. | ||

| + | |||

| + | De Jong, N. & Perfetti, C.A. (2011). Fluency training in the ESL classroom: An experimental study of fluency development and proceduralization. ''Language Learning'', ''61'', 533-568. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Vercellotti, M.L. & De Jong, N. (2010). How does fluency training in the ESL classroom affect language complexity? ''Poster presented at the Third Annual Inter-Science of Learning Center Conference.'', Boston, MA, March 2010. | ||

| + | |||

| + | De Jong, N. & Halderman, L.K. (2010). Vocabulary and grammatical knowledge contribute differentially to second language oral fluency. ''Paper presented at the Third Annual Inter-Science of Learning Center Conference.'' Boston, MA, March 2010. | ||

| + | |||

| + | De Jong, N. & Halderman, L. (2009). The role of vocabulary and grammar knowledge in second-language oral fluency: A correlational study. ''Paper presented at the Second Language Research Forum, East Lansing, MI'', October 2009. | ||

| + | |||

| + | De Jong, N. (2009). Pre-training formulaic sequences and its effect on oral fluency. ''Talk given at the SLA lab meeting, CUNY Graduate Center'', April 24, 2009. | ||

| + | |||

| + | De Jong, N., Halderman, L.K., & Ross, M. (2009). The effect of formulaic sequences training on fluency development in an ESL classroom. ''Paper presented at the American Association for Applied Linguistics conference 2009'', Denver, CO, March 2009. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <nowiki>*</nowiki> Vercellotti, M.L. & De Jong, N. (2009). “I prefer go”: English L2 Verb Complement Errors. ''Poster presented at the Georgetown University Round Table'', Washington, D.C., March 2009. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <nowiki>*</nowiki> Vercellotti, M.L. & De Jong, N. (2009). “I always dessert cake to diet”: Elicited Imitation as an L2 task. ''Poster presented at the Second Annual Inter-Science of Learning Center Conference'', Seattle, WA, February 2009. | ||

| + | |||

| + | De Jong, N. (2008). The study of oral fluency development in ESL. ''Presentation given at the Colloquium on Teaching and Learning World Languages, Queens College of CUNY'', March 2008. | ||

| + | |||

| + | De Jong, N. (2008). Oral fluency development in a second language. ''Presentation given at the Cognitive Approaches to Second Language Acquisition research group at the University of Amsterdam'', January 2008. | ||

| + | |||

| + | De Jong, N., (2007). Approaches to the study of second language acquisition. ''Guest lecture at the CUNY Graduate Center'', December 2007. | ||

| + | |||

| + | De Jong, N., (2007). Oral fluency development in ESL classrooms. ''Guest lecture at the CUNY Graduate Center'', November 2007. | ||

| + | |||

| + | De Jong, N., McCormick, D., O'Neill, C., and Bradin Siskin, C., (2007). Self-correction and fluency in ESL speaking development. ''Paper presented at the American Association for Applied Linguistics 2007 Conference'', Costa Mesa, California, April 2007. | ||

| + | |||

| + | De Jong, N., (2006) Developing oral fluency with the 4/3/2 task. ''Presentation given at the Multimedia Showcase'', University of Pittsburgh, September 2006. | ||

| + | |||

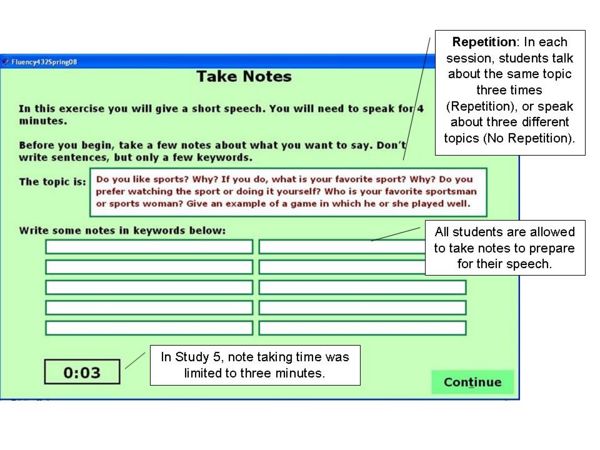

| + | ==Screen shots== | ||

| + | [[Image:Fluency_screenshot-notes.jpg|600px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Screenshot of the screen where students take notes before they start speaking | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

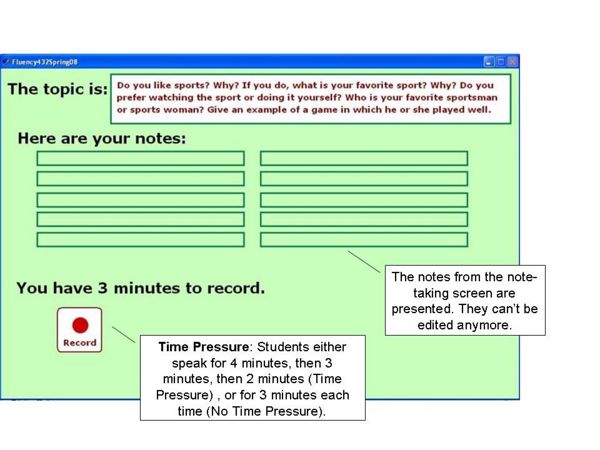

| + | [[Image:Fluency_screenshot-speech.jpg|600px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Screenshot of the screen where students record their speeches | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

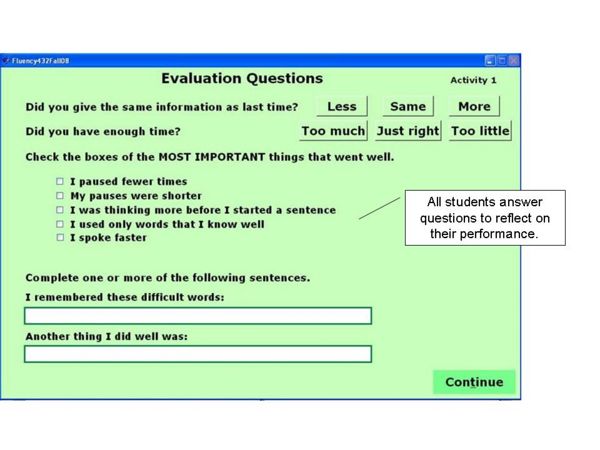

| + | [[Image:Fluency_screenshot-questions.jpg|600px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Screenshot of some of the questions after each speech has been recorded | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Fluency screenshot-picture-story-prompts.jpg|800px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Screenshot of sample picture story prompt | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==DataShop== | |

| + | Pretest and posttest data of Study 4 is available in [https://pslcdatashop.web.cmu.edu/DatasetInfo?datasetId=186 Datashop]. | ||

| + | Transcripts and audio files will be available through the TalkBank database. | ||

Latest revision as of 08:52, 14 September 2012

| Project title | Fostering fluency in second language learning: Testing two types of instruction |

|---|---|

| Principal Investigator | Dr. N. de Jong (faculty, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam) |

| Co-PIs | Dr. L.K. Halderman (post-doc, University of Pittsburgh) |

| Dr. C.A. Perfetti (faculty, University of Pittsburgh) | |

| Others with > 160 hours | Claire Siskin, Jessica Hogan, John laPlante, Mary Lou Vercellotti |

| Study start and end dates | Study 1: September - November 2006 |

| Study 2: January - March 2007 | |

| Study 3: January - March 2007 | |

| Study 4: January - March 2008 | |

| Study 5: September - November 2008 | |

| Study 6: October - December 2009 | |

| Study 7: Februari - March 2010 | |

| Study 8: October - December 2010 | |

| Learnlab | ESL, Speaking courses (levels 3, 4, 5) |

| Number of participants | 350 |

| Total Participant Hours | 825 hours |

| Datashop | Audio files and transcripts of Studies 1 through 4 are available |

| Current status | (July 2011) Paper about study 1 is published; paper about study 4 is under review; papers about studies 2 and 6 are in preparation. Many results have been presented at conferences.

Transcription and coding of studies 7 and 8 is in progress. Analysis of studies 5 and 6 is in progress. |

Contents

- 1 Abstract

- 2 Glossary

- 3 Research questions

- 4 Background and significance

- 5 Dependent variables

- 6 Independent variables

- 7 Hypotheses

- 8 Findings

- 8.1 Study 1: Repetition, proceduralization and L2 fluency

- 8.2 Study 2: Formulaic sequences

- 8.3 Study 3: Shadowing and formulaic sequences

- 8.4 Study 4: The role of vocabulary and grammar in L2 fluency (PRELIMINARY FINDINGS)

- 8.5 Study 5: Priming vocabulary and grammar for fluent production

- 8.6 Study 6: Piloting picture story prompts (PRELIMINARY FINDINGS)

- 9 Explanation

- 10 Further information

- 11 Descendants

- 12 Annotated bibliography

- 13 PSLC-related publications and presentations

- 14 Screen shots

- 15 DataShop

Abstract

Many studies have investigated the effect of exposure to language on fluency. It has been established, for instance, that fluency increases after a period of immersion or study abroad (Freed et al., 2004; Segalowitz & Freed, 2004). However, few types of instruction have been designed to increase oral fluency, and even fewer have been tested.

One such type of instruction is Nation’s 4/3/2 procedure, in which learners prepare a four-minute talk and repeat it twice to different partners, first in three minutes, then in two minutes (Nation, 1989). He found that the number of hesitations decreased in the retellings, and that sentences were more complex. We may characterize such an outcome as resulting from the fluency pressure exerted by the 4/3/2 procedure. It was not investigated, however, whether the effect transferred to new speeches, which is what we showed in Study 1. Another task that may increase fluency is shadowing, in which student talk along with a recording of a short speech by a native speaker. Shadowing may also increase the feature strength of formulaic sequences, resulting in faster access to them in subsequent production tasks.

This project is transformative in the sense that it moves research on fluency away from single- or multiple-case studies, using technology to collect and analyze larger amounts of oral production data (30 to 40 students per study), and to generate multiple measures of fluency, accuracy, and complexity. For example, not only articulation rate is measured, but also pause length, length of fluent run, and phonation/time ratio.

Study 1 investigated what characteristics of fluency are affected by the 4/3/2 procedure. Measures included the number of syllables per second (speech rate); mean length of fluent runs between pauses; phonation/time ratio; number of interphrasal and intraphrasal pauses; morphosyntactic accuracy; and number of embedded clauses (syntactic complexity). The posttest tested transfer to a different topic.

In Study 2 we investigated whether fluency is further enhanced by a pretraining of formulaic sequences, like the point is that, what I’m saying is that, and and so on). Fast and effortless access to these sequences frees up cognitive headroom which can then be used to construct sentences. This results in fewer and shorter pauses, and/or greater lexical and structural complexity.

Study 3 investigated whether shadowing leads to increased use of formulaic sequences (chunking) and native-like pauses in subsequent production tasks.

In studies 4 and 5 are investigating in further detail how the characteristics of the 4/3/2 task lead to fluency development. In Study 4a, we investigated how time pressure affects the benefits of repetition in terms of fluency, accuracy and complexity. We examined recordings both from the 4/3/2 task itself, and from long-term retention tests. In addition, we investigated the role of specific knowledge components in fluency development.

In Study 4b we tracked how the control and retrieval of specific vocabulary items and morphosyntactic structures develop as a result of the 4/3/2 training. Next, in Study 5, we examined whether priming these same items leads to greater accuracy and fluency during training and later. Data collection for Studies 4a, 4b and 5 took place in the Spring and Fall 2008 semesters, in the English as a Second Language (ESL) learnlab (level 4, higher intermediate). Data analysis is currently in progress.

(Posters presented in Spring 2009 are shown on the right. Click on the thumb images to see the larger images.)

Glossary

- 4/3/2 procedure

- A teaching method in which students talk about a topic for four minutes. Then they repeat their speech in three minutes, and again in two minutes.

- Shadowing

- Repeating speech while it is being spoken.

- Formulaic sequence

- A sequence, continuous or discontinuous, of words or other elements, which is, or appears to be, prefabricated (see Wray, 2002, p. 9), e.g., The point is that, What I'm trying to say is that, and Take something like.

- Articulation rate

- Number of syllables per second

- Phonation/time ratio

- The percentage of time spent speaking as a percentage proportion to the time taken to produce the speech sample

- Morphosyntactic accuracy

- In this study we will investigate subject-verb agreement, tense errors, definite/indefinite articles

- Syntactic complexity

- In this study we will investigate the number of embedded finite and non-finite clauses

Research questions

Study 1

- a. What characteristics of fluency are affected by repetition of a short speech under increasing time pressure (the 4/3/2 procedure)?

- b. Does knowledge refinement take place during the 4/3/2 training, in terms of morphosyntactic accuracy and syntactic complexity?

Study 2

- a. Does pretraining of formulaic sequences lead to an increase in their use in the subsequent 4/3/2 procedure and posttest? If so, does this increase overall fluency?

- b. Does proficiency level affect fluency development during the 4/3/2 procedure?

Study 3

- a. What characteristics of fluency are affected by shadowing a text with formulaic sequences and a pausing pattern characteristic of spontaneous speech?

- b. Does shadowing texts with formulaic sequences lead to an increase in their use in the posttest? If so, does this increase overall fluency?

For studies 2 and 3, questionnaire data were collected about the students' contact with the second language (English) and their first language, in terms of types of contact (e.g., listening to the radio, talking to friends, talking to strangers) and amount of contact (number of days per week, number of hours per day). We will explore whether these individual differences affect pretest performance and fluency development.

Study 4

- a. How do time pressure and repetition affect fluency, accuracy and complexity in the 4/3/2 task?

- b. Which knowledge components contribute to fluency development in the 4/3/2 task?

Study 5

- Does priming lead to an immediate and a long-term increase in fluency, accuracy and complexity?

Study 6 - pilot for studies 7 and 8

- What prompts will be most appropriate for studies 7 and 8 (to test the effect of time pressure on fluency, accuracy, and complexity)?

Study 7

- What is the effect of increasing time pressure on fluency, accuracy, and complexity in immediately repeated speeches?

Study 8

- What is the long-term effect of increasing time pressure on fluency, accuracy, and complexity?

Background and significance

Many studies in the field of second language acquisition that have studied fluency have investigated the effect of study abroad, immersion and regular classroom practice on fluency (Freed, Segalowitz, and Dewey, 2004; Segalowitz & Freed, 2004). Very few studies, however, have investigated specific activities that lead to fluency, which can be done in classrooms. Two such activities are tested in this project.

The first activity that is tested is the 4/3/2 procedure as proposed by Nation (1989). He investigated the development of fluency during this task, but used a limited number of measures and did not test the long-term effect: he only analyzed fluency during the task itself, not during the following weeks. This project will test the long-term effect and will include more measures, such as length and location of pauses. An attempt will be made to link these measures to cognitive mechanisms.

A general effect of the 4/3/2 task on fluency development was found in Study 1. The effect was investigated in more detail in Study 4a, focusing on the two main characteristics of the task: repetition and increasing time pressure.

The contribution of knowledge components is tested in Studies 2, 4b and 5. In Study 2, students received a pretraining of a set of formulaic sequences before the first 4/3/2 fluency training session. In Study 5 students received a pretraining at the start of each 4/3/2 fluency training session. The knowledge components in this pretraining was selected based on the results of Study 4b, which investigated the role of vocabulary breadth, vocabulary depth and grammatical knowledge in oral fluency.

Study 3 investigated whether shadowing affected fluency development. In addition, it was tested whether the presence of formulaic sequences in the model speeches increased use of those sequences in later speaking tasks, and whether such an increase affected fluency measures.

Dependent variables

Fluency, accuracy, and complexity

- Temporal measures of fluency:

- Articulation rate: number of syllables per second

- Pauses:

- mean length of fluent runs between pauses

- mean length of pauses

- phonation/time ratio

- number of interphrasal and intraphrasal pauses

- Formulaic sequences: number of appropriate formulaic sequences repeated from training

- Accuracy: morphosyntactic accuracy (target-like use of several structures, including subject-verb agreement, tense errors, and definite/indefinite articles; see Mizera, 2006: 71)

- Complexity: number of embedded finite and non-finite clauses (cf. Nation, 1989); lexical variety as measured by the Mean Segmental Type-Token Ratio (Towell, Hawkins & Bazergui, 1996)

Transfer

- Near transfer, immediate and delayed, normal post-test: After completing the last training session, students performed a similar task (spontaneous speech about a given topic), to test whether any gains in fluency during the training task were maintained in a new instance of the same task. This test was given one week and four weeks after the last training session, each time with a different topic. These recordings were made as part of the Recorded Speaking Activities (RSAs) from the project "The self-correction of speech errors (McCormick, O’Neill & Siskin)".

- Far transfer, delayed: The delayed posttests in Study 4 will include measures of vocabulary breadth, vocabulary depth and grammatical knowledge.

Independent variables

(For screenshots exemplifying some of the independent variables, see Screenshots below.)

- Studies 1-3: Pretest vs. immediate posttest vs. long-term retention posttest

- Study 1: Repetition vs. No Repetition

- In the Repetition condition students talk about one topic three times. In the No Repetition condition, students talk about three different topics.

- Study 2:

- a. Pretraining vs. no pretraining of formulaic sequences

- In the Formulaic Sequences condition, students receive a short training of a number of formulaic sequences before they start the fluency training (4/3/2 task). In the No Formulaic Sequences condition, students do not receive this pretraining, and only do the 4/3/2 task.

- b. Low intermediate vs. high intermediate proficiency level

- Low intermediate students are enrolled in ELI Speaking courses at level 3, high intermediate at level 4.

- Study 3: Shadowing text with formulaic sequences vs. without formulaic sequences

- In the Formulaic Sequences condition, students shadow texts that contain formulaic sequences. In the No Formulaic Sequences condition, students shadow the same texts, from which the formulaic sequences that are being studied have been removed.

- Study 4:

- a. Repetition vs. No Repetition

- The 4/3/2 task will include either 1 topic (repeated) or 3 topics (not repeated)

- b. Increasing Time Pressure vs. No Increasing Time Pressure

- The 4/3/2 task will include recordings of either 4, 3 and 2 minutes, or 3, 3, and 3 minutes

- Study 5: Pretraining vs. no pretraining of vocabulary and grammar knowledge components

- In the Pretraining condition, students perform short tasks before the 4/3/2 training sessions to prime their vocabulary and grammar knowledge. Students in the No Pretraining condition do not receive this pretraining.

Hypotheses

Study 1

- It is hypothesized that repetition of a short speech (independent variable) under increasing time pressure (fluency pressure) increases articulation rate and sentence complexity (dependent variables), and decreases the number and length of pauses (dependent variables). The reason is that repetition will--temporarily--increase the availability of vocabulary and sentence structures (leading to increase speech rate, short and fewer pauses), leaving more cognitive headroom for other processes (higher accuracy and syntactic complexity).

Study 2

- It is hypothesized that the presence of a pretraining of formulaic sequences (independent variable) leads to an increase in their use in subsequent spontaneous speech (dependent variable). Effortless use of these sequences will free up cognitive headroom for sentence structure planning, which may lead to overall more fluent performance, in terms of speed and pausing patterns (dependent variables). Thus, the training of formulaic sequences may accelerate future learning.

- Students at different proficiency levels may benefit in different ways from the 4/3/2 training. At lower proficiency levels, repetition may facilitate the use of particular words and grammar, leading to more instances of correct usage of vocabulary, morphosyntax and syntax. At higher proficiency levels, on the other hand, repetition may lead to a greater number of reformulations resulting in higher complexity.

Study 3

- It is hypothesized that shadowing a speech that contains formulaic sequences (independent variable) leads to an increase in their use in subsequent spontaneous speech (dependent variable). Since effortless use of these sequences will free up headroom for sentence structure planning, performance may become more fluent overall, in terms of speed and pausing patterns (dependent variables). Thus, shadowing may accelerate future learning. In addition, shadowing a text with target-language pausing patterns is expected to lead to a more native-like pausing pattern in subsequent spontaneous speech, mainly in terms of position (dependent variables: interphrasal and intraphrasal pauses).

Study 4

- Study 4 a: We hypothesize that time pressure in combination with speech repetition encourages a strategy of retrieval (shorter pauses, high lexical overlap between two subsequent recordings), while repetition without time pressure encourages computation, leading to higher accuracy and complexity with lower fluency. We expect that the strategy of computation may result in higher fluency in the longer term, because it leads to more refinement and strengthening of knowledge components, thus reducing hesitations and accelerating retrieval in future speeches (cf. the assistance dilemma).

- Study 4b: We hypothesize that students with a broader vocabulary—-since they have more words to choose from—-will be able to find an appropriate word more often and more quickly, and therefore speak more fluently (shorter and fewer pauses, fewer hesitations). This is a measure of individual differences, and of general vocabulary knowledge. Greater vocabulary depth will also increase fluency, because students have more control over vocabulary items. In addition, it is predicted that retrieval speed for words used in the fluency training will show a increase in retrieval speed compared to items that were used in the fluency training. Finally, we expect to find a positive correlation between fluency in speech production and the accuracy scores on a test of morphosyntactic knowledge.

Study 5

- We hypothesize that the pretraining will lead to more fluent speech production, as well as more accurate and more complex output. We expect that this effect will be retained on the posttest and delayed posttest. This would be an example of accelerated future learning through feature focusing.

Study 6

- This is an exploratory pilot study to test instructions and prompts for a new study, which will focus on the effect of time pressure on fluency and fluency developement (cf. Study 4a). The new speaking prompts will be picture stories, in order to create "pushed output" and to increase comparability of performance across students.

Study 7

This is a pilot study for Study 8, to examine the effect of time pressure on repeated and non-repeated story retellings. If a difference between the two groups is found, Study 8 will investigate the longer-term effects of time pressure.

- We hypothesize that time pressure in combination with speech repetition encourages a strategy of retrieval (shorter pauses, high lexical overlap between two subsequent recordings), while repetition without time pressure encourages computation, leading to higher accuracy and complexity with lower fluency. We expect that the strategy of computation may result in lower fluency in the short term (but higher fluency in the longer-term; see Study 8).

Study 8

This is a partial replication of Study 4, with tighter control over variables such as the content of the speeches, and with larger group sizes.

- We hypothesize that time pressure in combination with speech repetition encourages a strategy of retrieval (shorter pauses, high lexical overlap between two subsequent recordings), while repetition without time pressure encourages computation, leading to higher accuracy and complexity with lower fluency. We expect that the strategy of computation may result in higher fluency in the longer term, because it leads to more refinement and strengthening of knowledge components, thus reducing hesitations and accelerating retrieval in future speeches (cf. the assistance dilemma).

Robust learning

- Near transfer, immediate: In all studies, a posttest is administered about a week after the last training session. This will be a similar task—a 2-minute monologue—with new content—a new topic.

- Near transfer, retention: In Studies 1 and 2, another posttest is administered two to three weeks after the immediate posttest (three to four weeks after the last training session). Again, this will be a similar task—a 2-minute monologue—with new content—a new topic.

- Acceleration of future learning: In Study 5, the students in the experimental condition first receive a pretraining of a number of formulaic sequences. It will be tested whether their fluency, accuracy and syntactic complexity increases more during subsequent training, than of students who do not receive this pre-training.

Findings

Study 1: Repetition, proceduralization and L2 fluency

Fluency during the 4/3/2 task

During each training session, the mean length of fluent runs increased mostly for the two conditions in which speeches were repeated (Repetition and Control/Repetition). In addition, for all three groups, pauses, on average, became shorter, and phonation/time ratio increased (i.e., students were able to fill more time with speech).

Figures 1, 2 and 3 show the mean length of fluent runs for each recording in each of the sessions. It is clear that in sessions 1 and 2 the two conditions in which speeches were repeated pattern more closely together than the condition in which speeches were not repeated. The improvement in performance of the two repetition conditions seems more stable, whereas the performance of the No Repetition condition seems to be influenced by the topic of a particular speech.

Transfer to new topics