Difference between revisions of "Visual Representations in Science Learning"

(→Publications and Presentations) |

(→Further Information) |

||

| (80 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

Jodi Davenport | Jodi Davenport | ||

| + | ===Summary Table=== | ||

| + | Total Studies: 9<br> | ||

| + | Total Participants: 1994<BR> | ||

| + | Total Participant hours: 8997<BR> | ||

| + | <P> | ||

| + | Additional Contributors | ||

| + | * David Yaron | ||

| + | * David Klahr | ||

| + | * Ken Koedinger | ||

| + | * Michael Karabinos | ||

| + | * Gaea Leinhardt | ||

| + | * Jim Greeno | ||

| + | * Katie McEldoon | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Davenportsummary08.gif]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | {| border="1" cellspacing="0" cellpadding="5" style="text-align: left;" | ||

| + | | '''Lab study 1: Data available in DataShop''' || no log data collected <br> | ||

| + | * '''Pre/Post Test Score Data:''' No | ||

| + | * '''Paper or Online Tests:''' unknown | ||

| + | * '''Scanned Paper Tests:''' No | ||

| + | * '''Blank Tests:''' No | ||

| + | * '''Answer Keys: ''' No | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | '''Lab study 2: Data available in DataShop''' || no log data collected <br> | ||

| + | * '''Pre/Post Test Score Data:''' No | ||

| + | * '''Paper or Online Tests:''' unknown | ||

| + | * '''Scanned Paper Tests:''' No | ||

| + | * '''Blank Tests:''' No | ||

| + | * '''Answer Keys: ''' No | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | '''In Vivo 1: Data available in DataShop''' || [https://pslcdatashop.web.cmu.edu/DatasetInfo?datasetId=63 Dataset: Chemistry Buffer Study]<br> | ||

| + | * '''Pre/Post Test Score Data:''' No | ||

| + | * '''Paper or Online Tests:''' unknown | ||

| + | * '''Scanned Paper Tests:''' No | ||

| + | * '''Blank Tests:''' No | ||

| + | * '''Answer Keys: ''' No | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | '''In Vivo 2: Data available in DataShop''' || [https://pslcdatashop.web.cmu.edu/DatasetInfo?datasetId=63 Dataset: Chemistry Buffer Study]<br> | ||

| + | * '''Pre/Post Test Score Data:''' No | ||

| + | * '''Paper or Online Tests:''' unknown | ||

| + | * '''Scanned Paper Tests:''' No | ||

| + | * '''Blank Tests:''' No | ||

| + | * '''Answer Keys: ''' No | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | '''In Vivo 3: Data available in DataShop''' || [https://pslcdatashop.web.cmu.edu/DatasetInfo?datasetId=84 Dataset: Chemistry Buffer Study 2007]<br> | ||

| + | * '''Pre/Post Test Score Data:''' No | ||

| + | * '''Paper or Online Tests:''' unknown | ||

| + | * '''Scanned Paper Tests:''' No | ||

| + | * '''Blank Tests:''' No | ||

| + | * '''Answer Keys: ''' No | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | '''In Vivo 4: Data available in DataShop''' || [https://pslcdatashop.web.cmu.edu/DatasetInfo?datasetId=94 Dataset: CMU sp07 Buffers]<br> | ||

| + | * '''Pre/Post Test Score Data:''' No | ||

| + | * '''Paper or Online Tests:''' unknown | ||

| + | * '''Scanned Paper Tests:''' No | ||

| + | * '''Blank Tests:''' No | ||

| + | * '''Answer Keys: ''' No | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | '''In Vivo 5: Data available in DataShop''' || [https://pslcdatashop.web.cmu.edu/DatasetInfo?datasetId=94 Dataset: CMU sp07 Buffers]<br> | ||

| + | * '''Pre/Post Test Score Data:''' No | ||

| + | * '''Paper or Online Tests:''' unknown | ||

| + | * '''Scanned Paper Tests:''' No | ||

| + | * '''Blank Tests:''' No | ||

| + | * '''Answer Keys: ''' No | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | '''In Vivo 6: Data available in DataShop''' || [https://pslcdatashop.web.cmu.edu/DatasetInfo?datasetId=94 Dataset: CMU sp07 Buffers]<br> | ||

| + | * '''Pre/Post Test Score Data:''' No | ||

| + | * '''Paper or Online Tests:''' unknown | ||

| + | * '''Scanned Paper Tests:''' No | ||

| + | * '''Blank Tests:''' No | ||

| + | * '''Answer Keys: ''' No|- | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | '''In Vivo 7: Data available in DataShop''' || [https://pslcdatashop.web.cmu.edu/DatasetInfo?datasetId=204 Dataset: Chemistry Buffer Study 2008]<br> | ||

| + | * '''Pre/Post Test Score Data:''' No | ||

| + | * '''Paper or Online Tests:''' unknown | ||

| + | * '''Scanned Paper Tests:''' No | ||

| + | * '''Blank Tests:''' No | ||

| + | * '''Answer Keys: ''' No | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

=== Abstract === | === Abstract === | ||

| − | Visual representations, in the forms of diagrams, notation (e.g., equations), graphs and tables are fundamental tools in science instruction and practice. Whether diagrams or notational systems are helpful aids to problem solving depends critically on the content of the visual representation and how learners are able to process the information they contain. Expert/novice studies have demonstrated that different levels of experience | + | Visual representations, in the forms of diagrams, notation (e.g., equations), graphs and tables are fundamental tools in science instruction and practice. Whether diagrams or notational systems are helpful aids to problem solving depends critically on the content of the visual representation and how learners are able to process the information they contain. Expert/novice studies have demonstrated that different levels of experience result in differential processing of the same stimuli. However, it is not known how students are able to refine initially shallow understandings into meaningful chemical concepts or how the [[coordination]] of multiple representations helps with this process. |

| − | The current project seeks to determine | + | The current project seeks to determine 1) What is the expert mental model of chemical equilibrium systems 2) How do novices develop chemistry concepts and 3) What forms of instruction best enable students to acquire [[robust learning]] of chemical equilibrium. In particular, how and when does the use of multiple representations during instruction and problem solving lead to [[robust learning]], and how does instruction that interleaves chemical concepts with problem solving procedures enhance learning. To date, 9 studies (8 completed, 1 ongoing) have explored science learning at the two levels (micro and macro) of the theoretical framework. |

'''Microscopic Level: Identifying [[knowledge components]] and developing assessments''' | '''Microscopic Level: Identifying [[knowledge components]] and developing assessments''' | ||

| − | In order to assess robust learning, we conducted studies and collaborated with Chemistry and Education faculty (David Yaron, Gaea Leinhardt & Jim Greeno) to identify key knowledge components of equilibrium and acid base chemistry. For instance, a verbal protocol study has demonstrated that experts and novices differ in their ability to invoke relevant knowledge components in contexts involving different representations (e.g., chemical equations, graphs, and diagrams). We continue to create and revise new forms of assessments that identify which correct and incorrect knowledge components students have as they learn chemistry. | + | In order to assess robust learning, we conducted studies and collaborated with Chemistry and Education faculty (David Yaron, Gaea Leinhardt & Jim Greeno) to identify key knowledge components of equilibrium and acid base chemistry. For instance, a verbal protocol study has demonstrated that experts and novices differ in their ability to invoke relevant knowledge components in contexts involving different representations (e.g., chemical equations, graphs, and diagrams). We continue to create and revise new forms of assessments of knowledge [[transfer]] that identify which correct and incorrect knowledge components students have and apply as they learn chemistry. |

'''Macroscopic Level: Testing general learning principles''' | '''Macroscopic Level: Testing general learning principles''' | ||

| − | At the macroscopic level, ''in vivo'' studies test general learning principles. Studies have investigated whether the use of molecular-level diagrams increases robust learning as measured by transfer performance and have manipulated conditions to determine what type of instructional prompts will promote active processing. Early studies failed to find a learning advantage for molecular level diagrams and ongoing studies seek to determine what conditions may be required to produce a benefit of multiple representations during instruction. | + | At the macroscopic level, ''in vivo'' studies test general learning principles. Studies have investigated whether the use of molecular-level diagrams increases [[robust learning]] as measured by [[transfer]] performance and have manipulated conditions to determine what type of instructional prompts will promote active processing. Early studies failed to find a learning advantage for molecular level diagrams and ongoing studies seek to determine what conditions may be required to produce a benefit of multiple representations during instruction. We also test whether instruction that aligns instruction with an expert mental model of chemical reactions will improve problem solving performance and lead to [[robust learning]] in chemistry. |

=== Glossary === | === Glossary === | ||

| − | Visual representations: [[External representations]] that are used in instruction and problem solving such as diagrams, graphs, and equations | + | Visual representations: [[External representations]] that are used in instruction and problem solving such as diagrams, graphs, and equations. |

| + | |||

| + | === Hypothesis === | ||

| + | Chemical equilibrium is a difficult topic for students to learn as it involves learning a large set of [[knowledge components]] and applying these components flexibly in a variety of situations. As different representations make salient different key features of knowledge components, we hypothesize that instruction that requires the [[coordination]] of multiple representations will lead to more [[robust learning]] as measured by [[transfer]] tests such as conceptual multiple choice questions and open-ended inference questions. | ||

=== Research Questions === | === Research Questions === | ||

| − | Our project seeks to identify the [[knowledge components]] of equilibrium and acid base chemistry and determine when and how different types of representations lead to the acquisition of correct knowledge components | + | Our project seeks to identify the [[knowledge components]] of equilibrium and acid base chemistry and determine when and how [[coordination]] of different types of representations lead to the acquisition of correct knowledge components and [[robust learning]]. |

*What are the knowledge components of equilibrium and acid/base chemistry? (CMU, lab study #1, 2006; Chemistry working group) | *What are the knowledge components of equilibrium and acid/base chemistry? (CMU, lab study #1, 2006; Chemistry working group) | ||

| Line 23: | Line 108: | ||

*Does the presence of molecular level diagrams enhance robust learning of acid/base chemistry? (UBC, in vivo study #1, 2006; CMU, in vivo study #2, 2006) | *Does the presence of molecular level diagrams enhance robust learning of acid/base chemistry? (UBC, in vivo study #1, 2006; CMU, in vivo study #2, 2006) | ||

*Do molecular level diagrams enhance self explanation leading to robust learning in a tutorial on acids and bases? (CMU, lab study #2, 2006) | *Do molecular level diagrams enhance self explanation leading to robust learning in a tutorial on acids and bases? (CMU, lab study #2, 2006) | ||

| − | *Do | + | *Do labeled diagrams enhance robust learning as measured by transfer performance? (UBC, in vivo study #3, 2007; CMU, in vivo study #5, 2007) |

*Do virtual lab activities (in which multiple representations must be coordinated) enhance performance on interactive problem solving and transfer questions? (UBC, in vivo study #3, 2007) | *Do virtual lab activities (in which multiple representations must be coordinated) enhance performance on interactive problem solving and transfer questions? (UBC, in vivo study #3, 2007) | ||

*Does instruction with multiple representations including molecular level diagrams and graphs enhance the acquisition of equilibrium knowledge components leading to robust learning? (CMU, in vivo study #4, 2007) | *Does instruction with multiple representations including molecular level diagrams and graphs enhance the acquisition of equilibrium knowledge components leading to robust learning? (CMU, in vivo study #4, 2007) | ||

| + | *Does instruction that aligns an expert model of chemical reactions with problem solving procedures increase problem solving performances (CMU, in vivo study #6, 2007)? | ||

| + | *Does instruction that aligns an expert model of chemical reactions with problem solving procedures increase robust learning (CMU, in vivo study #7, 2008)? | ||

=== Background and Significance === | === Background and Significance === | ||

| − | + | Robust learning in chemistry is more than learning a set of facts or procedures. Instead, many pieces of knowledge must be acquired and flexibly coordinated in order to make predictions, inferences and analyses of chemical systems. We chose to focus on chemical equilibrium systems as the knowledge is important for understanding processes in chemistry, biology and engineering and the domain is notoriously difficult for students (e.g., Banerjee, 1991; Van Driel et al. 1999). | |

| + | |||

| + | As the knowledge components of chemical equilibrium are not necessarily explicit in textbooks or instructional materials, we have formed a Chemistry working group with Chemistry, Education and Learning Science faculty to identify core pieces of understanding in this domain. In addition, verbal protocol analyses help us understand student how students process instruction and solve chemistry problems. | ||

| − | + | Our hypothesis is that instruction and practice that includes a variety of representations will lead to robust learning. Multimedia instruction is widely believed to help chemistry learning by providing a bridge between the mathematical procedures and core chemistry concepts. For instance, chemistry education researchers have suggested that the ability to transform between representations leads to increased success in problem solving (Bodner & Domin, 2000) and that including diagrams during classroom instruction leads to improved conceptual understanding (Ardac & Akaygun, 2004; Bunce & Gabel, 2002; Noh & Scharmann, 1997; Sanger & Badger, 2001; Williamson & Abraham, 1995;see Kozma & Russell, 2005 for a review). Though the results of classroom studies are promising, the interventions often lasted many class periods and the content in the experimental and control classes was not tightly controlled, so it is unclear exactly how specific representations influenced learning. Further, assessments that demonstrated greater conceptual understanding did not always show increased problem solving performance. | |

| − | + | ||

| + | In a number of laboratory studies, Mayer (Clark & Mayer, 2003), Ainsworth & Loizou (2003) and others have found that instructional materials that include both diagrams and text provide learning benefits over materials that only include text. Will this same learning advantage extend to classroom-based instruction? Studies in chemistry education research have suggested that molecular level diagrams may promote deeper understanding that text or equations. However, these classroom-based studies lacked rigorous controls and assessments of robust learning. The current project investigates if and when the presence of visual representations in addition to text promotes deep conceptual understanding in chemistry. | ||

=== Independent Variables === | === Independent Variables === | ||

The studies in the project manipulate the presence of visual representations in chemistry instruction and problem solving. | The studies in the project manipulate the presence of visual representations in chemistry instruction and problem solving. | ||

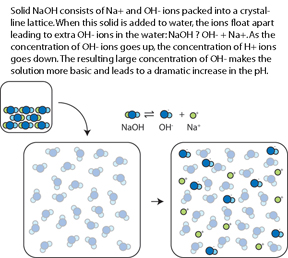

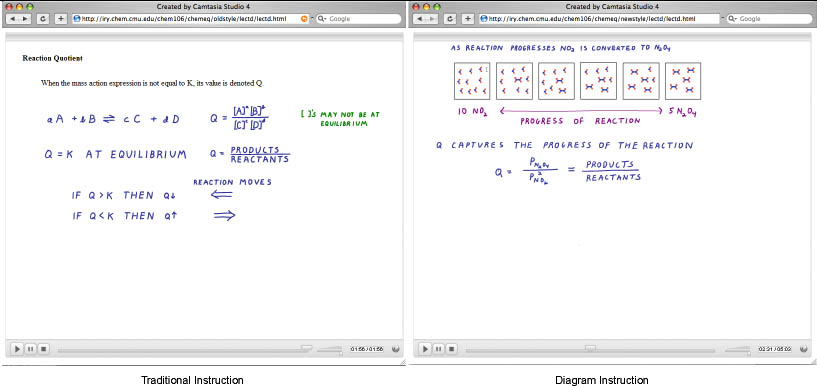

| − | For instance, in | + | For instance, in the (CMU, 2006) Lab Study #1, experts and novices solved problems in diffferent representational formats. The traditional format, found in many textbooks, involves a chemical equation and text-based setup. The diagram format requires solvers to additionally integrate pictorial information.<br> |

| + | '''Examples of Traditional and Diagram Formats''' | ||

| + | <br> | ||

[[Image:trad_diag.jpg]]<br> | [[Image:trad_diag.jpg]]<br> | ||

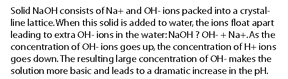

| − | In studies testing the role of molecular-level representations in chemistry instruction, text is identical in both conditions and the diagram condition supplements the text with pictures.<br> | + | In studies testing the role of molecular-level representations in chemistry instruction (Lab Study #2, ''in vivo'' Studies #1, #2, #3 and #5), text is identical in both conditions and the diagram condition supplements the text with pictures.<br> |

| + | '''Text-Only''' | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | [[Image:mole_pic_txt.jpg]] | ||

| + | '''Text+Diagram'''<br> | ||

[[Image:mole_pic.jpg]] | [[Image:mole_pic.jpg]] | ||

| − | === | + | === Dependent Variables === |

| − | + | Dependent variables include improvement from pre to post test on conceptual multiple choice questions, performance on scaffolded problem solving with tutors and performance on open-ended [[transfer]] questions. | |

| + | |||

| + | ''[[Transfer]] Questions''<BR> | ||

| + | Our studies use a range of transfer assessments | ||

| + | *Conceptual Multiple Choice | ||

| + | **E.g. You have 5 weak acids in your laboratory and want to create a series of buffer solutions. If the target pH is 4.3 which weak acid you would use to create your buffer, and would you use more weak base, weak acid or the same amount of each? | ||

| + | :::Weak acid A pKa = 7.35 | ||

| + | :::Weak acid B pKa = 7.15 | ||

| + | :::Weak acid C pKa = 6 | ||

| + | :::Weak acid D pKa = 4.3 | ||

| + | :::Weak acid E pKa = 6.5 | ||

| + | *Open-ended Transfer Questions | ||

| + | ** E.g., "How could you make a solution of lemon juice that is more acidic than a solution of hydrocholoric acid?" | ||

| + | *Scaffolded Problem Solving with tutors | ||

| + | *Virtual Laboratory Problems | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''[[Normal post-test]]'' Assessments<BR> | ||

| + | Include: | ||

| + | *Definitions: Defining terms such as acid/base | ||

| + | *True/False questions | ||

=== Findings === | === Findings === | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ====Expert/Novice Equilibrium Problem Solving: Lab study #1 ==== | |

| + | N = 16 (CMU, 2006) Lab Study #1 | ||

| + | |||

| + | The two aims of this study were 1) to create a taxonomy of knowledge components for equilibrium chemistry and 2) to determine whether problem representation led to differences in application of knowledge components. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A knowledge decomposition was carried out on the transcribed protocols and a taxonomy of equilibrium knowledge components has been created. | ||

| + | |||

| + | =====Findings Summary===== | ||

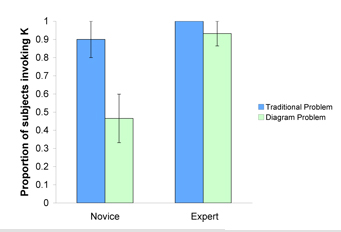

| + | To assess whether problem representation influenced the application of knowledge components, experts and novices solved equilibrium problems in different contexts while talking aloud. While experts were equally able to retrieve the correct [[knowledge component]] (in this case that the equilibrium constant, K, was required for problem solving), novices were able to retrieve the correct knowledge component when solving a traditional problem, but were less successful on problems using molecular-level diagrams. There was a significant main effect of expertise, F(1,13) = 9.15, p = .01, and an interaction between expertise and problem type, F (1, 13) = 5.205, p = .04. <br> | ||

[[Image:K_exnov.jpg]]<br> | [[Image:K_exnov.jpg]]<br> | ||

| − | < | + | ====Learning with molecular level diagrams: ''In vivo'' studies #1 and #2==== |

| − | + | N = 42 (UBC, 2006) ''in vivo'' Study #1<BR> | |

| + | N = 89 (CMU, 2006) ''in vivo'' Study #2 | ||

| + | |||

| + | The aim of these studies was to determine whether molecular level diagrams lead to increased performance on transfer questions after reading a tutorial that either contained Text+Diagram, or Text Only. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Results (UBC, 2006) ''in vivo'' Study #1 | ||

| + | *An ANCOVA was run on posttest scores with format (Diagram+Text vs. Text Only) as a between-subjects variable and pretest scores as a covariate. No significant effect of condition was found, F(1, 39) = .025, p = .88. Posttest scores were similar regardless of whether students were in the diagrams (M =.72) or text-only (M = .72) conditions. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Results (CMU, 2006) ''in vivo'' Study #2 | ||

| + | *A mixed 2x2 ANOVA was carried out with format (Diagram+Text vs. Text-only) as a between-subjects variable, time of test (Pre vs. Posttest) as a within-subjects variable and multiple-choice accuracy as the dependent variable. Pretest to posttest gains were significant, F(1, 87) = 94.4, p < .001, but there was no effect of format, and no interaction between test-time and format. See table below. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ::[[image:Earli_tables.gif]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | =====Findings summary===== | ||

| + | Results of these studies suggest no advantage for the addition of diagrams to text. Specifically, acid/base chemistry tutorials that included molecular-level diagrams did not produce enhanced learning compared with text-only versions of the same tutorials. Future studies will investigate whether labeled diagrams will be more likely to promote [[integration]] of textual material with visual representations, leading to more robust learning of chemistry concepts. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Molecular level diagrams and self explanation: Lab study #2==== | ||

| + | N = 22 (CMU, 2006) Lab Study #2 | ||

| + | |||

| + | As no benefits were found from the ''in vivo'' studies, we conducted a lab study to determine whether there were any processing differences in the Text+Diagram and Diagram Only conditions. Participants were instructed to self explain as they read through a tutorial on acid/base chemistry. | ||

| − | + | =====Findings Summary===== | |

| + | * Students made substantial learning gains from pre to post-test, p < .001. However, no significant main effect of condition was found for either the multiple choice test or performance on the definition questions F(1,20) < 1. Further, no main effect of condition was found for performance on transfer questions. | ||

| + | :[[Image:CMUabtut.jpg]] | ||

| − | + | * Transcribed protocols were analysed for time on task and number of words. There were no significant differences between conditions. | |

| + | * Verbal protocols were coded for Self Explanations (Noticing Coherence, Elaborations or Principle Based) and Monitoring statements (Positive or Negative). No significant differences in number of self explanations were found between conditions. | ||

| + | * Correlations: Significant correlations were found between the number of self explanations (SE) and transfer performance. In the Text Only condition, SE total was positively correlated with transfer performance (.642), however in the Diagrams+Text condition, SE total was negatively correlated with transfer performance (-.606). These results suggest that the diagrams in this particular study may have generated less germane processing. An analysis of the protocol data revealed that students in the Text Only condition made a greater number of causal self-explanations than students in the Diagram+Text condition. | ||

| − | [[Image: | + | ====Learning from labeled molecular level diagrams and Virtual Lab activities: ''In vivo'' study #3, UBC, 2007==== |

| + | N = 1139 (UBC, 2007) ''in vivo'' Study #3 | ||

| + | |||

| + | This study was an extension of ''in vivo'' Studies #1 and #2. The aims of this study were 1) to determine whether labeled diagrams would lead to greater learning advantages and 2) To determine whether Virtual Lab activities enhance problem-solving performance with scaffolded, interactive tutors. The lack of effect of diagrams in the earlier studies may have been due to the lack of labels with the diagrams. Prior work may have confounded the study of labels with diagrams and it is possible that only labeled diagrams promote the active processing required for learning gains from the [[coordination]] or [[integration]] of representations. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The 2x2 design varied format (Diagrams + Text vs. Text Only) and the order of Virtual Lab and problem-solving tutors (Virtual Lab first vs. Virtual Lab second.) Out of 1139 students, 812 completed the entire activity. The results found no significant differences of either Format or order of presentation F < 1 in both conditions. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====The influence of multiple representations on knowledge component acquisition in chemical equilibrium: ''In vivo'' study #4==== | ||

| + | N = 172 (CMU, 2007) ''in vivo'' Study #4 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Our knowledge decomposition of chemical equilibrium (informed by Lab Studies #1 and #2) as well as discussions with our Chemistry working group have revealed that the key knowledge component of "progress of reaction" is left implicit in many types of traditional instruction. For this study two sets of online lectures were created by Prof. Yaron to determine if instruction that uses multiple representations to convey the notion of progress of reaction would lead to more robust learning of chemistry concepts. Traditional instruction described equilibrium using chemical notations and text, the New instruction described equilibrium using molecular diagrams depicting the progress of reaction. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:ScreenShot.jpg]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Transfer]] measures of open-ended responses and conceptual multiple choice questions were collected and revealed that diagrams that were aligned with the progress of reaction framework increased learning, particularly for low knowledge students. | ||

| + | |||

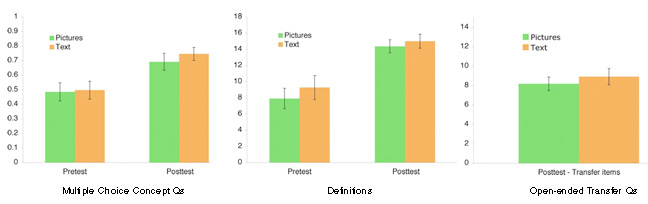

| + | [[Image:Text dia low.gif]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Molecular level diagrams and robust learning of acid base buffer concepts: ''In vivo'' study #5==== | ||

| + | N = 172 (CMU, 2007) ''in vivo'' Study #5 | ||

| + | |||

| + | This study was an extension of ''in vivo'' studies #1 and #2 that manipulate the presence of molecular level diagrams in a Chemistry tutorial. In addition to collecting pretest and posttest [[transfer]] measures, we also collected transfer performance on each page of the tutorial to determine which knowledge components are accessed in the Diagram+Text versus the Diagram Condition. | ||

| + | |||

| + | While students made significant improvements from pre to posttest, the format of instruction did not affect performance on either normal or transfer measures (F < 1 for all tests). The results of study #4 suggest that diagrams may only influence learning when the design of the representation, the cognitive processing of the learner and the specific learning objectives are all considered. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Coordinating chemistry concepts with problem solving to enhance learning: Classroom comparison study #6==== | ||

| + | N = 344 (CMU, 2004, 2007) Classroom Comparison Study #6 | ||

| + | |||

| + | While expert chemists are able to flexibly apply domain knowledge when | ||

| + | reasoning about chemical systems, students often fail to grasp core concepts | ||

| + | and rely on rote procedures for problem solving. In order to develop | ||

| + | interactive instruction that allows students to gain mastery in chemistry, | ||

| + | our project uses a 3-step approach: 1) Use cognitive task analysis to | ||

| + | determine how experts reason about equilibrium system, 2) Develop a model of | ||

| + | expert knowledge and 3) Develop instruction that makes explicit the | ||

| + | coordination of core concepts (i.e., expert knowledge) and problem solving | ||

| + | procedures. In a classroom study, we compared students that received traditional instruction in Dr. Yaron's 2004 class with students that received our new instruction in Dr. Yaron's 2007 class. We found that the new instruction led to a 2.5x increase | ||

| + | in problem solving performance. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:DavenportYaron.jpg]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Concept development in chemistry learning: ''In vivo'' study #7==== | ||

| + | N = ~ 170 (CMU, 2008) "in vivo" Study #7 | ||

| + | |||

| + | In this ongoing study, we further investigate the promising findings of Study #6 to determine whether the new instruction leads to improvement on conceptual understanding measures as well as transfer problem solving performance. A variety of pretest questions tap into student conceptions of equilibrium, formative assessments track changes in these conceptions and posttests measure transfer and long term retention. Our goal is to understand what knowledge components are strengthened through the new instruction and whether these knowledge components are able to be applied in new settings, [[transfer]] and are retained for at least a month after instruction, [[long-term retention]]. | ||

| − | |||

=== Explanation === | === Explanation === | ||

| − | Our expert-novice protocol study revealed that experts are more likely to invoke a | + | The knowledge decomposition of chemical equilibrium has revealed a number of correct knowledge components to be acquired by students and incorrect knowledge components to be avoided. This taxonomy has been used to create assessments used in our studies. |

| + | |||

| + | Our expert-novice protocol study revealed that experts are more likely to invoke a relevant [[knowledge component]] across different problem types than novice solvers. This result suggests that many students maintain a shallow understanding of chemical systems even after completing a year of college-level chemistry. Current studies are addressing whether instruction that ties the core concept of progress of reaction (identified through the expert/novice studies) to multiple representations will lead to more [[robust learning]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Our studies testing learning benefits for visual diagrams during instruction suggest the large effects of diagrams commonly found in laboratory studies of topics such as bicycle pumps, lightning formation and disc brakes may be difficult to replicate in educational settings. Active and intentional coordination of representations may be required if diagrams are to increase learning and the mere presence of diagrams does not guarantee this type of active processing. Current studies seek to determine whether labeled diagrams will enhance the coordination of text and diagrams via [[sense making]]. Further, prior work has not closely mapped the features of to-be-learned material to the information contained in diagrams and text. In our ongoing studies, we are investigating which pieces of information are contained in text, which are contained in the diagrams, and which features students are able to extract when they are presented with multiple representations. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ===References=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Ardac, D. & Akaygun, S. (2004). Effectiveness of multimedia-based instruction that emphasizes molecular representations on students’ understanding of chemical | ||

| + | change. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 41(4), 317-337. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Banerjee, A. C. (1991). Misconceptions of students and teachers in chemical equilibrium. International Journal of Science Education 13: 487–494. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Bunce, D., & Gable, D. (2002). Differential effects on the achievement of males and females of teaching the particulate nature of chemistry. Journal of Research in | ||

| + | Science Teaching, 39(10), 911-927. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Sanger, M. & Badger, S. (2001). Using computer-based visualization strategies to improve students’ understanding of molecular polarity and miscibility. Journal of | ||

| + | Chemical Education, 78(10), 1412-14-16. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Noh, T. & Scharmann, L. (1997). Instructional influence of a molecular-level pictorial presentation of matter on students’ conceptions and problem-solving ability. | ||

| + | Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 34(2), 199217. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Van Driel, J. H., de Vos W., and Verloop, N. (1999). Introducing dynamic equilibrium as an explanatory model. Journal of Chemical Education 76: 559–561. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Williamson, V. & Abraham, M. (1995). The effects of computer animation on the particulate mental models of college chemistry students. Journal of Research in | ||

| + | Science Teaching, 32(5), 521-534. | ||

| − | |||

=== Publications and Presentations === | === Publications and Presentations === | ||

| − | Davenport, J.L., Klahr, D. & Koedinger (2007). The influence of diagrams on chemistry learning. Paper | + | Davenport, J. L., Yaron, D., Klahr, D., & Koedinger, K. (2008). When do diagrams enhance learning? A framework for designing relevant representations. Paper accepted for the 2008 International Conference of the Learning Sciences, June 2008. [http://learnlab.org/uploads/mypslc/publications/davenporticls08final.pdf download] |

| + | |||

| + | Davenport, J. L., Yaron, D., Klahr, D., & Koedinger, K. (2008). Coordinating chemistry concepts with problem solving to enhance learning. Poster presented at the Open Learning Interplay Symposium in Pittsburgh, PA. [http://learnlab.org/uploads/mypslc/talks/davenportoli08poster.pdf download] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Davenport, J. L., Yaron, D., Klahr, D., & Koedinger, K. (2008). When do diagrams enhance science learning? Presented at the First Annual Inter-Science of Learning Center conference in Pittsburgh, PA. [http://learnlab.org/uploads/mypslc/publications/davenport_islc.pdf download] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Davenport, J.L., McEldoon, K. & Klahr, K. (2007). Depicting invisible processes: The influence of molecular-level diagrams in Chemistry instruction. Poster presented at the 29th Annual meeting of the Cognitive Science Society. August 2007. [http://www.learnlab.org/uploads/mypslc/publications/cogsci07davenport.pdf download] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Davenport, J.L., Yaron, D., Karabinos, M., Klahr, K. & Koedinger, K. (2007). Chemical equilibrium: an evaluation of a new type of instruction. Poster presented at the Gordon Conference for Chemistry Education Research and Practice. June 2007. [http://www.learnlab.org/uploads/mypslc/publications/davenport_gordon07.pdf download] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Davenport, J.L., Klahr, D. & Koedinger (2007). The influence of diagrams on chemistry learning. Paper presented at the 12th Biennial Conference of the European Association for Research on Learning and Instruction. August 2007. [http://www.learnlab.org/uploads/mypslc/publications/davenportearli07.pdf download] | ||

| − | Davenport, J.L., Klahr, D. & Koedinger ( | + | Davenport, J.L., Klahr, D. & Koedinger (2006). The influence of external representations on chemistry problem solving. Poster presented at the Forty-seventh Annual Meeting of the Psychonomic Society in Houston, Texas. November 2006. [http://www.learnlab.org/uploads/mypslc/publications/davenport06.pdf download] |

| − | Yaron, D., Karabinos, M., Davenport, J. & Leinhardt, G. Virtual labs and scenario-based activities for introductory chemistry. American Chemical Society - Penn-Ohio Regional Meeting, | + | Yaron, D., Karabinos, M., Davenport, J. & Leinhardt, G. Virtual labs and scenario-based activities for introductory chemistry. American Chemical Society - Penn-Ohio Regional Meeting, Thiel College, Greenville, PA, October 2006. |

Yaron, D., Karabinos, M., Davenport, J. & Leinhardt, G. Virtual lab activities for introductory chemistry labs, American Chemical Society Annual Meeting, San Francisco, September 2006. | Yaron, D., Karabinos, M., Davenport, J. & Leinhardt, G. Virtual lab activities for introductory chemistry labs, American Chemical Society Annual Meeting, San Francisco, September 2006. | ||

| − | Yaron, D., Karabinos, M., Davenport, J. & Leinhardt, G. Virtual labs activities for introductory chemistry. Biennial Conference on Chemical Education, | + | Yaron, D., Karabinos, M., Davenport, J. & Leinhardt, G. Virtual labs activities for introductory chemistry. Biennial Conference on Chemical Education, Purdue University, West Layefette In, July 2006. |

Yaron, D., Karabinos, M., Davenport, J., Cuadros, J., Rehm, E., McCue, W., Dennis, D., Leinhardt, G. and Evans, K. The ChemCollective Virtual Lab and Other Online Materials. Presented at Duke University, Durham, NC, November 2005. | Yaron, D., Karabinos, M., Davenport, J., Cuadros, J., Rehm, E., McCue, W., Dennis, D., Leinhardt, G. and Evans, K. The ChemCollective Virtual Lab and Other Online Materials. Presented at Duke University, Durham, NC, November 2005. | ||

| Line 85: | Line 310: | ||

[[Category:Study]] | [[Category:Study]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Data available in DataShop]] | ||

Latest revision as of 20:17, 15 December 2010

Contents

- 1 Visual Representations in Science Learning

- 1.1 Summary Table

- 1.2 Abstract

- 1.3 Glossary

- 1.4 Hypothesis

- 1.5 Research Questions

- 1.6 Background and Significance

- 1.7 Independent Variables

- 1.8 Dependent Variables

- 1.9 Findings

- 1.9.1 Expert/Novice Equilibrium Problem Solving: Lab study #1

- 1.9.2 Learning with molecular level diagrams: In vivo studies #1 and #2

- 1.9.3 Molecular level diagrams and self explanation: Lab study #2

- 1.9.4 Learning from labeled molecular level diagrams and Virtual Lab activities: In vivo study #3, UBC, 2007

- 1.9.5 The influence of multiple representations on knowledge component acquisition in chemical equilibrium: In vivo study #4

- 1.9.6 Molecular level diagrams and robust learning of acid base buffer concepts: In vivo study #5

- 1.9.7 Coordinating chemistry concepts with problem solving to enhance learning: Classroom comparison study #6

- 1.9.8 Concept development in chemistry learning: In vivo study #7

- 1.10 Explanation

- 1.11 References

- 1.12 Publications and Presentations

- 1.13 Further Information

Visual Representations in Science Learning

Jodi Davenport

Summary Table

Total Studies: 9

Total Participants: 1994

Total Participant hours: 8997

Additional Contributors

- David Yaron

- David Klahr

- Ken Koedinger

- Michael Karabinos

- Gaea Leinhardt

- Jim Greeno

- Katie McEldoon

| Lab study 1: Data available in DataShop | no log data collected

|

| Lab study 2: Data available in DataShop | no log data collected

|

| In Vivo 1: Data available in DataShop | Dataset: Chemistry Buffer Study

|

| In Vivo 2: Data available in DataShop | Dataset: Chemistry Buffer Study

|

| In Vivo 3: Data available in DataShop | Dataset: Chemistry Buffer Study 2007

|

| In Vivo 4: Data available in DataShop | Dataset: CMU sp07 Buffers

|

| In Vivo 5: Data available in DataShop | Dataset: CMU sp07 Buffers

|

| In Vivo 6: Data available in DataShop | Dataset: CMU sp07 Buffers

|

| In Vivo 7: Data available in DataShop | Dataset: Chemistry Buffer Study 2008

|

Abstract

Visual representations, in the forms of diagrams, notation (e.g., equations), graphs and tables are fundamental tools in science instruction and practice. Whether diagrams or notational systems are helpful aids to problem solving depends critically on the content of the visual representation and how learners are able to process the information they contain. Expert/novice studies have demonstrated that different levels of experience result in differential processing of the same stimuli. However, it is not known how students are able to refine initially shallow understandings into meaningful chemical concepts or how the coordination of multiple representations helps with this process.

The current project seeks to determine 1) What is the expert mental model of chemical equilibrium systems 2) How do novices develop chemistry concepts and 3) What forms of instruction best enable students to acquire robust learning of chemical equilibrium. In particular, how and when does the use of multiple representations during instruction and problem solving lead to robust learning, and how does instruction that interleaves chemical concepts with problem solving procedures enhance learning. To date, 9 studies (8 completed, 1 ongoing) have explored science learning at the two levels (micro and macro) of the theoretical framework.

Microscopic Level: Identifying knowledge components and developing assessments In order to assess robust learning, we conducted studies and collaborated with Chemistry and Education faculty (David Yaron, Gaea Leinhardt & Jim Greeno) to identify key knowledge components of equilibrium and acid base chemistry. For instance, a verbal protocol study has demonstrated that experts and novices differ in their ability to invoke relevant knowledge components in contexts involving different representations (e.g., chemical equations, graphs, and diagrams). We continue to create and revise new forms of assessments of knowledge transfer that identify which correct and incorrect knowledge components students have and apply as they learn chemistry.

Macroscopic Level: Testing general learning principles At the macroscopic level, in vivo studies test general learning principles. Studies have investigated whether the use of molecular-level diagrams increases robust learning as measured by transfer performance and have manipulated conditions to determine what type of instructional prompts will promote active processing. Early studies failed to find a learning advantage for molecular level diagrams and ongoing studies seek to determine what conditions may be required to produce a benefit of multiple representations during instruction. We also test whether instruction that aligns instruction with an expert mental model of chemical reactions will improve problem solving performance and lead to robust learning in chemistry.

Glossary

Visual representations: External representations that are used in instruction and problem solving such as diagrams, graphs, and equations.

Hypothesis

Chemical equilibrium is a difficult topic for students to learn as it involves learning a large set of knowledge components and applying these components flexibly in a variety of situations. As different representations make salient different key features of knowledge components, we hypothesize that instruction that requires the coordination of multiple representations will lead to more robust learning as measured by transfer tests such as conceptual multiple choice questions and open-ended inference questions.

Research Questions

Our project seeks to identify the knowledge components of equilibrium and acid base chemistry and determine when and how coordination of different types of representations lead to the acquisition of correct knowledge components and robust learning.

- What are the knowledge components of equilibrium and acid/base chemistry? (CMU, lab study #1, 2006; Chemistry working group)

- How do experts and novices differ in equilibrium problem solving with multiple representations? (CMU, lab study #1, 2006)

- Does the presence of molecular level diagrams enhance robust learning of acid/base chemistry? (UBC, in vivo study #1, 2006; CMU, in vivo study #2, 2006)

- Do molecular level diagrams enhance self explanation leading to robust learning in a tutorial on acids and bases? (CMU, lab study #2, 2006)

- Do labeled diagrams enhance robust learning as measured by transfer performance? (UBC, in vivo study #3, 2007; CMU, in vivo study #5, 2007)

- Do virtual lab activities (in which multiple representations must be coordinated) enhance performance on interactive problem solving and transfer questions? (UBC, in vivo study #3, 2007)

- Does instruction with multiple representations including molecular level diagrams and graphs enhance the acquisition of equilibrium knowledge components leading to robust learning? (CMU, in vivo study #4, 2007)

- Does instruction that aligns an expert model of chemical reactions with problem solving procedures increase problem solving performances (CMU, in vivo study #6, 2007)?

- Does instruction that aligns an expert model of chemical reactions with problem solving procedures increase robust learning (CMU, in vivo study #7, 2008)?

Background and Significance

Robust learning in chemistry is more than learning a set of facts or procedures. Instead, many pieces of knowledge must be acquired and flexibly coordinated in order to make predictions, inferences and analyses of chemical systems. We chose to focus on chemical equilibrium systems as the knowledge is important for understanding processes in chemistry, biology and engineering and the domain is notoriously difficult for students (e.g., Banerjee, 1991; Van Driel et al. 1999).

As the knowledge components of chemical equilibrium are not necessarily explicit in textbooks or instructional materials, we have formed a Chemistry working group with Chemistry, Education and Learning Science faculty to identify core pieces of understanding in this domain. In addition, verbal protocol analyses help us understand student how students process instruction and solve chemistry problems.

Our hypothesis is that instruction and practice that includes a variety of representations will lead to robust learning. Multimedia instruction is widely believed to help chemistry learning by providing a bridge between the mathematical procedures and core chemistry concepts. For instance, chemistry education researchers have suggested that the ability to transform between representations leads to increased success in problem solving (Bodner & Domin, 2000) and that including diagrams during classroom instruction leads to improved conceptual understanding (Ardac & Akaygun, 2004; Bunce & Gabel, 2002; Noh & Scharmann, 1997; Sanger & Badger, 2001; Williamson & Abraham, 1995;see Kozma & Russell, 2005 for a review). Though the results of classroom studies are promising, the interventions often lasted many class periods and the content in the experimental and control classes was not tightly controlled, so it is unclear exactly how specific representations influenced learning. Further, assessments that demonstrated greater conceptual understanding did not always show increased problem solving performance.

In a number of laboratory studies, Mayer (Clark & Mayer, 2003), Ainsworth & Loizou (2003) and others have found that instructional materials that include both diagrams and text provide learning benefits over materials that only include text. Will this same learning advantage extend to classroom-based instruction? Studies in chemistry education research have suggested that molecular level diagrams may promote deeper understanding that text or equations. However, these classroom-based studies lacked rigorous controls and assessments of robust learning. The current project investigates if and when the presence of visual representations in addition to text promotes deep conceptual understanding in chemistry.

Independent Variables

The studies in the project manipulate the presence of visual representations in chemistry instruction and problem solving.

For instance, in the (CMU, 2006) Lab Study #1, experts and novices solved problems in diffferent representational formats. The traditional format, found in many textbooks, involves a chemical equation and text-based setup. The diagram format requires solvers to additionally integrate pictorial information.

Examples of Traditional and Diagram Formats

In studies testing the role of molecular-level representations in chemistry instruction (Lab Study #2, in vivo Studies #1, #2, #3 and #5), text is identical in both conditions and the diagram condition supplements the text with pictures.

Text-Only

Dependent Variables

Dependent variables include improvement from pre to post test on conceptual multiple choice questions, performance on scaffolded problem solving with tutors and performance on open-ended transfer questions.

Transfer Questions

Our studies use a range of transfer assessments

- Conceptual Multiple Choice

- E.g. You have 5 weak acids in your laboratory and want to create a series of buffer solutions. If the target pH is 4.3 which weak acid you would use to create your buffer, and would you use more weak base, weak acid or the same amount of each?

- Weak acid A pKa = 7.35

- Weak acid B pKa = 7.15

- Weak acid C pKa = 6

- Weak acid D pKa = 4.3

- Weak acid E pKa = 6.5

- Open-ended Transfer Questions

- E.g., "How could you make a solution of lemon juice that is more acidic than a solution of hydrocholoric acid?"

- Scaffolded Problem Solving with tutors

- Virtual Laboratory Problems

Normal post-test Assessments

Include:

- Definitions: Defining terms such as acid/base

- True/False questions

Findings

Expert/Novice Equilibrium Problem Solving: Lab study #1

N = 16 (CMU, 2006) Lab Study #1

The two aims of this study were 1) to create a taxonomy of knowledge components for equilibrium chemistry and 2) to determine whether problem representation led to differences in application of knowledge components.

A knowledge decomposition was carried out on the transcribed protocols and a taxonomy of equilibrium knowledge components has been created.

Findings Summary

To assess whether problem representation influenced the application of knowledge components, experts and novices solved equilibrium problems in different contexts while talking aloud. While experts were equally able to retrieve the correct knowledge component (in this case that the equilibrium constant, K, was required for problem solving), novices were able to retrieve the correct knowledge component when solving a traditional problem, but were less successful on problems using molecular-level diagrams. There was a significant main effect of expertise, F(1,13) = 9.15, p = .01, and an interaction between expertise and problem type, F (1, 13) = 5.205, p = .04.

Learning with molecular level diagrams: In vivo studies #1 and #2

N = 42 (UBC, 2006) in vivo Study #1

N = 89 (CMU, 2006) in vivo Study #2

The aim of these studies was to determine whether molecular level diagrams lead to increased performance on transfer questions after reading a tutorial that either contained Text+Diagram, or Text Only.

Results (UBC, 2006) in vivo Study #1

- An ANCOVA was run on posttest scores with format (Diagram+Text vs. Text Only) as a between-subjects variable and pretest scores as a covariate. No significant effect of condition was found, F(1, 39) = .025, p = .88. Posttest scores were similar regardless of whether students were in the diagrams (M =.72) or text-only (M = .72) conditions.

Results (CMU, 2006) in vivo Study #2

- A mixed 2x2 ANOVA was carried out with format (Diagram+Text vs. Text-only) as a between-subjects variable, time of test (Pre vs. Posttest) as a within-subjects variable and multiple-choice accuracy as the dependent variable. Pretest to posttest gains were significant, F(1, 87) = 94.4, p < .001, but there was no effect of format, and no interaction between test-time and format. See table below.

Findings summary

Results of these studies suggest no advantage for the addition of diagrams to text. Specifically, acid/base chemistry tutorials that included molecular-level diagrams did not produce enhanced learning compared with text-only versions of the same tutorials. Future studies will investigate whether labeled diagrams will be more likely to promote integration of textual material with visual representations, leading to more robust learning of chemistry concepts.

Molecular level diagrams and self explanation: Lab study #2

N = 22 (CMU, 2006) Lab Study #2

As no benefits were found from the in vivo studies, we conducted a lab study to determine whether there were any processing differences in the Text+Diagram and Diagram Only conditions. Participants were instructed to self explain as they read through a tutorial on acid/base chemistry.

Findings Summary

- Students made substantial learning gains from pre to post-test, p < .001. However, no significant main effect of condition was found for either the multiple choice test or performance on the definition questions F(1,20) < 1. Further, no main effect of condition was found for performance on transfer questions.

- Transcribed protocols were analysed for time on task and number of words. There were no significant differences between conditions.

- Verbal protocols were coded for Self Explanations (Noticing Coherence, Elaborations or Principle Based) and Monitoring statements (Positive or Negative). No significant differences in number of self explanations were found between conditions.

- Correlations: Significant correlations were found between the number of self explanations (SE) and transfer performance. In the Text Only condition, SE total was positively correlated with transfer performance (.642), however in the Diagrams+Text condition, SE total was negatively correlated with transfer performance (-.606). These results suggest that the diagrams in this particular study may have generated less germane processing. An analysis of the protocol data revealed that students in the Text Only condition made a greater number of causal self-explanations than students in the Diagram+Text condition.

Learning from labeled molecular level diagrams and Virtual Lab activities: In vivo study #3, UBC, 2007

N = 1139 (UBC, 2007) in vivo Study #3

This study was an extension of in vivo Studies #1 and #2. The aims of this study were 1) to determine whether labeled diagrams would lead to greater learning advantages and 2) To determine whether Virtual Lab activities enhance problem-solving performance with scaffolded, interactive tutors. The lack of effect of diagrams in the earlier studies may have been due to the lack of labels with the diagrams. Prior work may have confounded the study of labels with diagrams and it is possible that only labeled diagrams promote the active processing required for learning gains from the coordination or integration of representations.

The 2x2 design varied format (Diagrams + Text vs. Text Only) and the order of Virtual Lab and problem-solving tutors (Virtual Lab first vs. Virtual Lab second.) Out of 1139 students, 812 completed the entire activity. The results found no significant differences of either Format or order of presentation F < 1 in both conditions.

The influence of multiple representations on knowledge component acquisition in chemical equilibrium: In vivo study #4

N = 172 (CMU, 2007) in vivo Study #4

Our knowledge decomposition of chemical equilibrium (informed by Lab Studies #1 and #2) as well as discussions with our Chemistry working group have revealed that the key knowledge component of "progress of reaction" is left implicit in many types of traditional instruction. For this study two sets of online lectures were created by Prof. Yaron to determine if instruction that uses multiple representations to convey the notion of progress of reaction would lead to more robust learning of chemistry concepts. Traditional instruction described equilibrium using chemical notations and text, the New instruction described equilibrium using molecular diagrams depicting the progress of reaction.

Transfer measures of open-ended responses and conceptual multiple choice questions were collected and revealed that diagrams that were aligned with the progress of reaction framework increased learning, particularly for low knowledge students.

Molecular level diagrams and robust learning of acid base buffer concepts: In vivo study #5

N = 172 (CMU, 2007) in vivo Study #5

This study was an extension of in vivo studies #1 and #2 that manipulate the presence of molecular level diagrams in a Chemistry tutorial. In addition to collecting pretest and posttest transfer measures, we also collected transfer performance on each page of the tutorial to determine which knowledge components are accessed in the Diagram+Text versus the Diagram Condition.

While students made significant improvements from pre to posttest, the format of instruction did not affect performance on either normal or transfer measures (F < 1 for all tests). The results of study #4 suggest that diagrams may only influence learning when the design of the representation, the cognitive processing of the learner and the specific learning objectives are all considered.

Coordinating chemistry concepts with problem solving to enhance learning: Classroom comparison study #6

N = 344 (CMU, 2004, 2007) Classroom Comparison Study #6

While expert chemists are able to flexibly apply domain knowledge when reasoning about chemical systems, students often fail to grasp core concepts and rely on rote procedures for problem solving. In order to develop interactive instruction that allows students to gain mastery in chemistry, our project uses a 3-step approach: 1) Use cognitive task analysis to determine how experts reason about equilibrium system, 2) Develop a model of expert knowledge and 3) Develop instruction that makes explicit the coordination of core concepts (i.e., expert knowledge) and problem solving procedures. In a classroom study, we compared students that received traditional instruction in Dr. Yaron's 2004 class with students that received our new instruction in Dr. Yaron's 2007 class. We found that the new instruction led to a 2.5x increase in problem solving performance.

Concept development in chemistry learning: In vivo study #7

N = ~ 170 (CMU, 2008) "in vivo" Study #7

In this ongoing study, we further investigate the promising findings of Study #6 to determine whether the new instruction leads to improvement on conceptual understanding measures as well as transfer problem solving performance. A variety of pretest questions tap into student conceptions of equilibrium, formative assessments track changes in these conceptions and posttests measure transfer and long term retention. Our goal is to understand what knowledge components are strengthened through the new instruction and whether these knowledge components are able to be applied in new settings, transfer and are retained for at least a month after instruction, long-term retention.

Explanation

The knowledge decomposition of chemical equilibrium has revealed a number of correct knowledge components to be acquired by students and incorrect knowledge components to be avoided. This taxonomy has been used to create assessments used in our studies.

Our expert-novice protocol study revealed that experts are more likely to invoke a relevant knowledge component across different problem types than novice solvers. This result suggests that many students maintain a shallow understanding of chemical systems even after completing a year of college-level chemistry. Current studies are addressing whether instruction that ties the core concept of progress of reaction (identified through the expert/novice studies) to multiple representations will lead to more robust learning.

Our studies testing learning benefits for visual diagrams during instruction suggest the large effects of diagrams commonly found in laboratory studies of topics such as bicycle pumps, lightning formation and disc brakes may be difficult to replicate in educational settings. Active and intentional coordination of representations may be required if diagrams are to increase learning and the mere presence of diagrams does not guarantee this type of active processing. Current studies seek to determine whether labeled diagrams will enhance the coordination of text and diagrams via sense making. Further, prior work has not closely mapped the features of to-be-learned material to the information contained in diagrams and text. In our ongoing studies, we are investigating which pieces of information are contained in text, which are contained in the diagrams, and which features students are able to extract when they are presented with multiple representations.

References

Ardac, D. & Akaygun, S. (2004). Effectiveness of multimedia-based instruction that emphasizes molecular representations on students’ understanding of chemical change. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 41(4), 317-337.

Banerjee, A. C. (1991). Misconceptions of students and teachers in chemical equilibrium. International Journal of Science Education 13: 487–494.

Bunce, D., & Gable, D. (2002). Differential effects on the achievement of males and females of teaching the particulate nature of chemistry. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 39(10), 911-927.

Sanger, M. & Badger, S. (2001). Using computer-based visualization strategies to improve students’ understanding of molecular polarity and miscibility. Journal of Chemical Education, 78(10), 1412-14-16.

Noh, T. & Scharmann, L. (1997). Instructional influence of a molecular-level pictorial presentation of matter on students’ conceptions and problem-solving ability. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 34(2), 199217.

Van Driel, J. H., de Vos W., and Verloop, N. (1999). Introducing dynamic equilibrium as an explanatory model. Journal of Chemical Education 76: 559–561.

Williamson, V. & Abraham, M. (1995). The effects of computer animation on the particulate mental models of college chemistry students. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 32(5), 521-534.

Publications and Presentations

Davenport, J. L., Yaron, D., Klahr, D., & Koedinger, K. (2008). When do diagrams enhance learning? A framework for designing relevant representations. Paper accepted for the 2008 International Conference of the Learning Sciences, June 2008. download

Davenport, J. L., Yaron, D., Klahr, D., & Koedinger, K. (2008). Coordinating chemistry concepts with problem solving to enhance learning. Poster presented at the Open Learning Interplay Symposium in Pittsburgh, PA. download

Davenport, J. L., Yaron, D., Klahr, D., & Koedinger, K. (2008). When do diagrams enhance science learning? Presented at the First Annual Inter-Science of Learning Center conference in Pittsburgh, PA. download

Davenport, J.L., McEldoon, K. & Klahr, K. (2007). Depicting invisible processes: The influence of molecular-level diagrams in Chemistry instruction. Poster presented at the 29th Annual meeting of the Cognitive Science Society. August 2007. download

Davenport, J.L., Yaron, D., Karabinos, M., Klahr, K. & Koedinger, K. (2007). Chemical equilibrium: an evaluation of a new type of instruction. Poster presented at the Gordon Conference for Chemistry Education Research and Practice. June 2007. download

Davenport, J.L., Klahr, D. & Koedinger (2007). The influence of diagrams on chemistry learning. Paper presented at the 12th Biennial Conference of the European Association for Research on Learning and Instruction. August 2007. download

Davenport, J.L., Klahr, D. & Koedinger (2006). The influence of external representations on chemistry problem solving. Poster presented at the Forty-seventh Annual Meeting of the Psychonomic Society in Houston, Texas. November 2006. download

Yaron, D., Karabinos, M., Davenport, J. & Leinhardt, G. Virtual labs and scenario-based activities for introductory chemistry. American Chemical Society - Penn-Ohio Regional Meeting, Thiel College, Greenville, PA, October 2006.

Yaron, D., Karabinos, M., Davenport, J. & Leinhardt, G. Virtual lab activities for introductory chemistry labs, American Chemical Society Annual Meeting, San Francisco, September 2006.

Yaron, D., Karabinos, M., Davenport, J. & Leinhardt, G. Virtual labs activities for introductory chemistry. Biennial Conference on Chemical Education, Purdue University, West Layefette In, July 2006.

Yaron, D., Karabinos, M., Davenport, J., Cuadros, J., Rehm, E., McCue, W., Dennis, D., Leinhardt, G. and Evans, K. The ChemCollective Virtual Lab and Other Online Materials. Presented at Duke University, Durham, NC, November 2005.