Difference between revisions of "Gifted"

(→Giftedness and Motivation as Seperate Factors) |

(→References) |

||

| (37 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

2) possesses and unusual capacity for leadership or | 2) possesses and unusual capacity for leadership or | ||

| − | + | [[Image:Normal Distribution.jpg|thumb|Normal Distribution]] | |

3) excels in a specific academic field | 3) excels in a specific academic field | ||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

Within studies that use IQ tests, the The common cutoff for giftedness is one standard deviation above the mean, or 84th percentile and above. | Within studies that use IQ tests, the The common cutoff for giftedness is one standard deviation above the mean, or 84th percentile and above. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Giftedness and Motivation== | ||

The split in the role of motivation and giftedness is between those that theorize giftedness as being a mixture of talent and motivation and those that theorize giftedness as innate talent. | The split in the role of motivation and giftedness is between those that theorize giftedness as being a mixture of talent and motivation and those that theorize giftedness as innate talent. | ||

| − | ==Giftedness and Motivation as | + | ===Motivation as Facilitating Giftedness=== |

| + | |||

| + | Considered the traditional approach to giftedness, this theory looks at the ability of the gifted individual as playing the largest role in the development of gifted behavior. A popular model for this theory is the Differentiated Models of Giftedness and Talent (DMGT). Proposed by Francoys Gange, this model places a distinction between gift and later talent. Natural ability or gift is the inherited ability of the person, and can be intellectual, creative, socioaffective or sensory motor. Talent is the how, through a series of affecters, this gift is expressed. The talent may be in a variety of areas, such as academics, the arts, or sports. | ||

| + | [[Image:Gagne, 2000.jpg|thumb|Gagne (2000) Ten Commandments for Academic Talent Development]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Among the traditional views, this can be considered an advanced one. Whereas older theories saw raw gift as the sole measure for later talent, this model sees various affecters as playing a moderating role. One of the affecters that aids the development of talent is motivation (cited as an intrapersonal catalyst). Among these catalysts are also self-awareness, environmental catalysts, and even chance is accounted for. Yet for the considerations and advancements it makes, we see how each of these catalysts remains just that, a catalyst. Their primary role continues to be as assisting the development of the talent and thus limited by the magnitude of the natural ability. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The 6 affecters of natural ability into talent in the DMGT are 1) the natural ability or gift 2) chance 3) intrapersonal catalyst 4) environmental catalyst 5) learning/practice and 6) talent. Gift is not only an indication of the individual’s ability, but also indicates a level of specificity. In this case natural ability can be intellectual, creative, etc, and with varying degrees of each. Chance is seen as simply how chance plays into development and accounts for the randomness of the child’s development. Intrapersonal catalysts include motivation and self discipline as well as how personality traits develop ability. Environmental catalysts look at how external factors, like parents and teachers, facilitate development. Learning and practice are given the a larger role over the catalysts mentioned in development of natural talent. This not only shapes talent in how strong it is, but also contextually (such as either arts or academics). Finally, talent is the developmental endpoint and is as contextually specific as natural ability. Talent thus has a variety of areas that it develops into, such as sports or social action. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Motivation as a Central role in Giftedness=== | ||

| + | [[Image:Dai, Moon, Feldhusen (1998).jpg|thumb|Socio-Contextual Model]] | ||

| + | Modern theories on giftedness see motivation as playing a much larger role in not only it’s development, but it’s expressed behavior. One example is proposed by Gottfried and Gottfried as seeing “motivation as an area of giftedness in and of itself.” The theoretical background for this is based on the belief that the results of academic measures, whether they be IQ tests or standardized scores, are dictated to a large extent by motivation. A gifted score would be seen as measuring gifted behavior instead of actual gifted ability. Motivation as well as determination are thus seen as compensating for a lower gifted ability. Advancing this idea, this theory holds true that having a large amount of natural ability is gifted ability in the same way that having a large amount of determination and motivation would be considered gifted ability. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Gottfried and Gottfried tested this method by testing gifted children in the Children’s Academic Intrinsic Motivation Inventory (CAIMI) as well as looking at additional academic and intellectual measures such as IQ, GPA, SAT scores, and drop out rate. Participants were measured at 6 month intervals from infancy through high school. The results found saw that motivation had a more positive relationship with achievement than IQ. Achievement including GPA and standardized test scores. Additionally, the ratings of academic intrinsic motivation remained stable during adolescents. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Additionally to the results, Gottfried and Gottfried saw that the identification of gifted level academic motivation was easily detected by teachers. This is somewhat expected considering that two very different theories (the Gottfried and Gottfried as well as the Gange model) hold parents and teachers as a part of their model. Yet they differ in how the child interacts with these affecters. In the Gange model, we see it on the same level of interaction as motivation, that is to say as a catalyst facilitating natural ability. Yet in Gottfried and Gottfried model sees the child’s seeking of extra stimulation and motivation to interact with what is given by the parents and teacher as the gifted behavior. In other words, rather than the interaction enhancing ability, it is the interaction that becomes the motivational ability. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Gifted but Underachieving=== | ||

| + | [[Image:Optimal zone of motivation.jpg|thumb|Optimal zone of motivation]] | ||

| + | Gifted underachievers are considered students whose achievement levels are below those expected by their high intellectual ability. As stated by Dai, Moon, and Feldhausen, these students have been seen as having a variety of behavioral characteristics. Csikszentmihalyi's theory of optimal zone of motivation offers a strong theoretical basis for this occurrence. The theory states that the ability of a student on a task is best when kept close to their max ability level(flow). When a task is either more or less challenging than this level, it discourages the child either through boredom or anxiety. With gifted children, because their ability is higher than their peers, most tasks would result in a state of boredom. Thus, this lack of motivation may be the source of the student's lack of achievement. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Empirical studies have also tried to tap into possible reasons for underachievement. One study found these students take credit for success yet shun failure (Laffoon, Jenkins-Friedman, & Tollefson, 1989) while another saw these students as aware that their lack of effort was the source of their academic shortcomings (Davis & Connell, 1985). Though establishing person relevance to school has alleviated the number of gifted underachievers (Emerick, 1992), it remains that this population has certain qualities that make a single solution effective. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==References== | ||

| + | Gagne, F. (2007) Ten Commandments for Academic Talent Development, Gifted Child Quarterly,52, 2, 93-118 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Barab, S.A., Plucker, J.A. (2002) Smart People or Smart Contexts? Cognition, Ability, and Talent Development in an Age of Situated Approaches to Knowing and Learning, Educational Psychologist, 37:3, 165-182 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Gottfried, A.E. & Gottfried, A.W. (2004) Toward the Development of a Conceptualization of Gifted Motivation, Gifted Child Quarterly, 48; 121 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Dai, D.Y., Moon, S.M., Feldhusen, J.F. (1998) Achievement Motivation and Gifted Students: A Social Cognitive Perspective, Educational Psychologist, 33:2, 45 - 63 | ||

| − | + | Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1975). Beyond boredom and ann'ety. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. | |

| − | + | Laffoon, K. S., Jenkins-Friedman, R., & Tollefson, N. (1989). Causal attributions of underachieving gifted, achieving gifted, and nongifted students. Journal for the Education ofthe Gifred, 13, 4-21. | |

| − | + | Emerick, L. J. (1992). Academic underachievement among the gifted: Students' perceptions of factors that reverse the pattern. Gifled Child Quarterly. 36, 140-146. | |

| − | + | Davis, H. B., & Connell, J. P. (1985). The effect of aptitude and achievement status on the self-system. Gifled Child Quarterly, 29, 131-136. | |

Latest revision as of 12:08, 26 March 2009

This page is reserved for work on the topic of intellectual giftedness and motivation.

Giftedness or Intellectual Giftedness is characterized by intellectual development in children that surpasses those of their same age. Gifted children often show greater ability at grasping harder academic concepts and at times greater creativity than those of their same grade level.

Contents

Measuring Intellectual Giftedness

Though all measures of giftedness attempt to classify students with intellectual ability higher than their peers, it continues to be heavily debated. In the United States public school system the classification of gifted individuals is reffered to as:

a child or youth who performs at or shows the potential for performing at a remarkably high level of accomplishment when compared to others of the same age, experience or environment and who:

1) exhibits high performance capability in an intellectual, creative, or artistic area

2) possesses and unusual capacity for leadership or

3) excels in a specific academic field

(74th legislature of the State of Texas, Chapter 29, Subchapter D, Section 29.121) Identifying Gifted Students

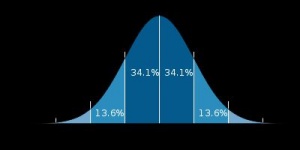

Yet even if the US public school identifies various factors as playing a part in giftedness, the IQ test is still considered to be the central tool in diagnosing giftedness. This is due to its consistency and high level of development, which allows for a particular student's scores to be measures against a very large sample's score.

Within studies that use IQ tests, the The common cutoff for giftedness is one standard deviation above the mean, or 84th percentile and above.

Giftedness and Motivation

The split in the role of motivation and giftedness is between those that theorize giftedness as being a mixture of talent and motivation and those that theorize giftedness as innate talent.

Motivation as Facilitating Giftedness

Considered the traditional approach to giftedness, this theory looks at the ability of the gifted individual as playing the largest role in the development of gifted behavior. A popular model for this theory is the Differentiated Models of Giftedness and Talent (DMGT). Proposed by Francoys Gange, this model places a distinction between gift and later talent. Natural ability or gift is the inherited ability of the person, and can be intellectual, creative, socioaffective or sensory motor. Talent is the how, through a series of affecters, this gift is expressed. The talent may be in a variety of areas, such as academics, the arts, or sports.

Among the traditional views, this can be considered an advanced one. Whereas older theories saw raw gift as the sole measure for later talent, this model sees various affecters as playing a moderating role. One of the affecters that aids the development of talent is motivation (cited as an intrapersonal catalyst). Among these catalysts are also self-awareness, environmental catalysts, and even chance is accounted for. Yet for the considerations and advancements it makes, we see how each of these catalysts remains just that, a catalyst. Their primary role continues to be as assisting the development of the talent and thus limited by the magnitude of the natural ability.

The 6 affecters of natural ability into talent in the DMGT are 1) the natural ability or gift 2) chance 3) intrapersonal catalyst 4) environmental catalyst 5) learning/practice and 6) talent. Gift is not only an indication of the individual’s ability, but also indicates a level of specificity. In this case natural ability can be intellectual, creative, etc, and with varying degrees of each. Chance is seen as simply how chance plays into development and accounts for the randomness of the child’s development. Intrapersonal catalysts include motivation and self discipline as well as how personality traits develop ability. Environmental catalysts look at how external factors, like parents and teachers, facilitate development. Learning and practice are given the a larger role over the catalysts mentioned in development of natural talent. This not only shapes talent in how strong it is, but also contextually (such as either arts or academics). Finally, talent is the developmental endpoint and is as contextually specific as natural ability. Talent thus has a variety of areas that it develops into, such as sports or social action.

Motivation as a Central role in Giftedness

Modern theories on giftedness see motivation as playing a much larger role in not only it’s development, but it’s expressed behavior. One example is proposed by Gottfried and Gottfried as seeing “motivation as an area of giftedness in and of itself.” The theoretical background for this is based on the belief that the results of academic measures, whether they be IQ tests or standardized scores, are dictated to a large extent by motivation. A gifted score would be seen as measuring gifted behavior instead of actual gifted ability. Motivation as well as determination are thus seen as compensating for a lower gifted ability. Advancing this idea, this theory holds true that having a large amount of natural ability is gifted ability in the same way that having a large amount of determination and motivation would be considered gifted ability.

Gottfried and Gottfried tested this method by testing gifted children in the Children’s Academic Intrinsic Motivation Inventory (CAIMI) as well as looking at additional academic and intellectual measures such as IQ, GPA, SAT scores, and drop out rate. Participants were measured at 6 month intervals from infancy through high school. The results found saw that motivation had a more positive relationship with achievement than IQ. Achievement including GPA and standardized test scores. Additionally, the ratings of academic intrinsic motivation remained stable during adolescents.

Additionally to the results, Gottfried and Gottfried saw that the identification of gifted level academic motivation was easily detected by teachers. This is somewhat expected considering that two very different theories (the Gottfried and Gottfried as well as the Gange model) hold parents and teachers as a part of their model. Yet they differ in how the child interacts with these affecters. In the Gange model, we see it on the same level of interaction as motivation, that is to say as a catalyst facilitating natural ability. Yet in Gottfried and Gottfried model sees the child’s seeking of extra stimulation and motivation to interact with what is given by the parents and teacher as the gifted behavior. In other words, rather than the interaction enhancing ability, it is the interaction that becomes the motivational ability.

Gifted but Underachieving

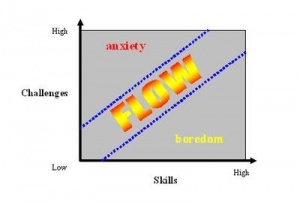

Gifted underachievers are considered students whose achievement levels are below those expected by their high intellectual ability. As stated by Dai, Moon, and Feldhausen, these students have been seen as having a variety of behavioral characteristics. Csikszentmihalyi's theory of optimal zone of motivation offers a strong theoretical basis for this occurrence. The theory states that the ability of a student on a task is best when kept close to their max ability level(flow). When a task is either more or less challenging than this level, it discourages the child either through boredom or anxiety. With gifted children, because their ability is higher than their peers, most tasks would result in a state of boredom. Thus, this lack of motivation may be the source of the student's lack of achievement.

Empirical studies have also tried to tap into possible reasons for underachievement. One study found these students take credit for success yet shun failure (Laffoon, Jenkins-Friedman, & Tollefson, 1989) while another saw these students as aware that their lack of effort was the source of their academic shortcomings (Davis & Connell, 1985). Though establishing person relevance to school has alleviated the number of gifted underachievers (Emerick, 1992), it remains that this population has certain qualities that make a single solution effective.

References

Gagne, F. (2007) Ten Commandments for Academic Talent Development, Gifted Child Quarterly,52, 2, 93-118

Barab, S.A., Plucker, J.A. (2002) Smart People or Smart Contexts? Cognition, Ability, and Talent Development in an Age of Situated Approaches to Knowing and Learning, Educational Psychologist, 37:3, 165-182

Gottfried, A.E. & Gottfried, A.W. (2004) Toward the Development of a Conceptualization of Gifted Motivation, Gifted Child Quarterly, 48; 121

Dai, D.Y., Moon, S.M., Feldhusen, J.F. (1998) Achievement Motivation and Gifted Students: A Social Cognitive Perspective, Educational Psychologist, 33:2, 45 - 63

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1975). Beyond boredom and ann'ety. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Laffoon, K. S., Jenkins-Friedman, R., & Tollefson, N. (1989). Causal attributions of underachieving gifted, achieving gifted, and nongifted students. Journal for the Education ofthe Gifred, 13, 4-21.

Emerick, L. J. (1992). Academic underachievement among the gifted: Students' perceptions of factors that reverse the pattern. Gifled Child Quarterly. 36, 140-146.

Davis, H. B., & Connell, J. P. (1985). The effect of aptitude and achievement status on the self-system. Gifled Child Quarterly, 29, 131-136.