In vivo experiment

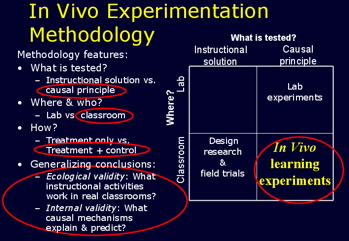

An in vivo experiment is a laboratory-style multi-condition experiment conducted in the classroom. The conditions manipulate a small but crucial, well-defined instructional variable, as opposed to a whole curriculum. How in vivo experimentation is related to other methodologies is illustrated in the following figure:

An in vivo experiment can be implemented either in a within (i.e. students are randomly assigned to conditions, regardless the class they belong to) or in a between classroom design (i.e. classes are randomly assigned to conditions).

In the PSLC, which uses tutoring systems and on-line course activities to monitor students' progress through the year, there are typically two types of in vivo experiments (to make this easier to follow, assume that there are just two conditions in the experiment, called the experimental and control conditions):

- The tutoring system is modified to implement the manipulation. Students assigned to the experimental condition do their work on the modified system; Students assigned to the control condition use the unmodified tutoring system. See Post-practice reflection (Katz) for an example.

- For a limited time, e.g., a one-hour classroom period or a two-hour lab period, the control students do one activity and the experimental students do another. The control activity typically is not one that students do during that period, but is nonetheless a common part of their normal instruction. For instance, they may watch a video of some problems being solved by their instructor. The tutoring system may or may not be involved with these activities. See Hausmann Study for an example.

Regardless of the experimental method used in an in vivo experiment, the tutoring systems record log data that are used to evaluate the effects of the manipulation.

In vivo experiments are not new, for instance, Aleven & Koedinger (2002). Going back further, there have been many classroom studies that have had important features of in vivo experiments. For example, below are summaries from two dissertations that were the basis of the famous Bloom (1984) 2-sigma paper. These dissertations involved 6 experiments. These experiments are borderline in vivo experiments because mastery and, particularly, tutoring are not "small well-defined instructional variables". Instead, these treatments actually varied a number of different instructional methods at one time. Nevertheless, they illustrate a number of other important features of in vivo experimentation.

Burke’s 1983 experiments measured immediate learning, far transfer and long-term retention.

Burke, A. J. (1983). Student's Potential for Learning Contrasted under Tutorial and Group Approaches to Instruction. Unpublished PhD, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL.

This was 3 in vivo experiment comparing conventional instruction, mastery learning and 3-on-1 human tutoring. E1 taught 4th graders probability; E2 taught 5th graders probability; E3 taught fifth graders probability at a different site. Instruction was 3-week module. Tutors were undergrad education students trained for a week to ask good questions and give good feedback (pg. 85). The mastery learning students had to achieve 80% to go on; the tutoring students had to achieve 90%. The conventional instruction students got no feedback from the mastery tests. On immediate post-testing, for lower mental process (like a normal post-test, table 5 pg. 98) tutoring effect sizes averaged 1.66 (with 1.53, 1.34 and 2.11 for E1, E2 and E3, respectively) and mastery learning averaged 0.85 (with .73, .78 and 1.04 for E1, E2 and E3). For higher mental process (like far transfer, Table 6 pg. 104), got for tutoring effect sizes averaged 2.11 (with 1.58, 2.65 and 2.11) and mastery learning averaged 1.19 (with 0.90, 1.47 and 1.21). For long-term retention 3 weeks later; in E3, the effect size for tutoring was 1.71 for lower mental processes vs. 1.01 for mastery learning. For higher mental processes, effect size was 1.99 for tutoring vs. 1.13 for mastery learning. The researchers also measured time on task (tutoring was higher percentage) and affect rates.

Anania, J. (1981). The Effects of Quality of Instruction on the Cognitive and Affective Learning of Students. Unpublished PhD, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL.

This project involved 3 in vivo experiments, each lasting 3 weeks, comparing conventional teaching, mastery learning and tutoring. The tutors were undergrad education students with no training in tutoring. E1 taught probability to 4th graders; E2 taught probability to 5th graders; E3 taught cartography to 8th graders. E1 and E2 used 3-on-1 tutoring; E3 used 1-on-1 tutoring. Measured immediate learning post-test, time on task, and affect measures. For gains (table 3, pg. 72), effect sizes for tutoring were 1.93 (average of 1.77, 2.06 and 1.95 for E1, E2 and E3) and for mastery learning were 1.00 (avg of 0.61, 1.29 and 1.10). The cutoff score for mastery learning as 80% (pg. 77) vs. 90% for tutoring (pg. 81).